|

David Joy's Diaries

Extracts from a published version Some Links in the Evolution of the Locomotive: the particulars extracted from the Diaries of the Late David Joy; edited G.A. Sekon.. Railway Magazine 1908 Volumes 22 & 23.

David Joy's Diaries are frequently cited, but are difficult to trace as full bibliographical references are rarely given (these are now available) and the originals are held by the Science Museum. This version uses Joy's text as possibly edited by Sekon, but has re-written most of the connecting text as Sekon is too florid for the Internet, and sometimes flew kites which have long since landed: Joy's own words are terse. Sekon's own introduction noted that he had concentrated almost entirely on his work with locomotives, leaving much of the other "interesting" material unreproduced. The connecting texts are shown in a smaller font and in colour (which may not reproduce on all browsers). Some of the spelling in the original appears to be eccentric and may be due to mid-nineteenth or early twenieth century ideas (or to the OCR software!). Sekon's biography has been used as the basis for the entry in the biographical section. . Note Part 2 covers valve gear..Summers (BackTrack, 18, 242) has some interesting comments on both the published transcripts and a microfilm copy of the original held by the Science Museum Library and argues that they, like the Gooch Diaries, were manicured for posterity, and are certainly not a daily record. The 4-2-4, the cause of Summers' quest is in Part 2.

The original diaries "are copiously illustrated by free hand drawings, from David Joy's own pen", and "to enable readers to enjoy more fully the perusal of the extracts from the diaries, many of Joy's illustrations have been re-drawn, and are reproduced as illustrations", but only the key ones have been loaded onto the website.

The initial entry reads:

I was born in Leeds, March 3rd, 1825, and do not remember the time when machinery did not interest me.

The first point I distinctly recall was when about six years old I made a model of the road-roller then in use. It was made of a silk-bobbin with pins for centres, and slips of wood for shafts. This bit of machinery was shown to an old friend of my father—William Lea, of "Brandy and Salt" Farm—and he said, patting me on the head: "The boy will be an engineer. I never forgot this.

In 1832 Joy first encountered a steam locomotive, the rack locomotive constructed by Murray on Blenkinsop's plan (cited as Blenkinsopp].

Living in Hunslet Lane, on the London Road, the old coal railway from the Middleton Pits into Leeds, ran behind our house a few fields off, and we used to see the steam from the engines rise above the trees. Once I remember going with my nurse, who held my hand (I had to stretch it up to hers, I was so little) while we stood to watch the engine with its train of coal-wagons pass. We were told it would come up like a flash of lightning, but it only came lumbering on like a cart.

Date 1835—or— 6,

July

We went to live in town that I could go to school—Hiley's,

Rockingham Street. At first I forgot machinery—till a boy, Hall, whose

father was a plumber, brought a little working model of a steam engine to

school. The master had it set to work in a lower room, and the big boys sat

round the table to see it. I climbed, up to see it through the window, and

remember it well. It was a beam engine, and stood on a box, and was painted

blue, the cylinder was a bit of lead pipe about 1½ in. diameter, and

the valves a four-way cock. When I got home I got a bit of lead pipe and

made futile attempts to make a steam engine myself.

Then another schoolfellow (Barraclough), whose father was owner or manager

of a cloth mill in Hunslet Lane, took me to see their mill engine, the

old-fashioned beam engine, with an upper floor for the beam support, of course.

At this time I had a sovereign given me to spend on tools (joiners' tools),

so I set to work to model this engine, like the

sketch.[In the Original Diaries a model

of a beam engine is given.]

June, 1838

Next came the Leeds Exhibition, under the auspices of the Mechanics'

Institution Committee. We boys had season tickets, and used to rush down

to see it in dinner hour, when the locomotive used to run round its circular

tour. The most I remember of it was (A) the tank, rockery and fountain; (B)

space for operator ; (C) circular railway ; (D) circular canal ; (E) the

crowd outside.

The most exciting exhibition was the locomotive. It was fired by charcoal

blown up with a pair of hand bellows.

Often the steam was blown up till the little beggar ran so fast that at last

he keeled over and toppled into the water with a splash and a fizz—we

watched for this.

Early 1840

Then I went to Wesley College, Sheffield, where my parents gave instructions for me to be pushed in all mechanical pursuits (Mr. Exley, was the master) ; also to be taught mechanical drawing, as Mr. E—— said, "So many people, having an idea, did not know how to put it down on paper."

December, 1840

This time we returned from school by railway, as the North Midland Railway, Derby to Leeds, had been opened in the half, with a branch to Sheffield. I perfectly remember the engine in the dark, early morning, but I saw httle more of it than its head light and broad, low smoke-box, and tall chimney. Any way, this was the first bonn fide railway engine I had ever seen. [In the Original Diaries a front elevation of the type employed is shown]

January, 1841

Back to school, with a fad for railway engines. I was then 16—March 3rd. I was now working hard at mechanical drawing, and also got hold of a copy of "Tredgold on the Steam Engine," which I devoured, often staying in on holiday afternoon to read. Here I found a sectional elevation of the most advanced locomotive of the day, a Stephenson with gab reversing gear. [drawing of gear in Original Diary.]

On the back of this page in the Diary, headed "An After Thought," is an account of a model locomotive made during the period January to June 1841. This "After Thought" is so long that, in addition to the drawing and writing on the back of the page, a sheet of foolscap is also inserted, written on both sides. It concludes with an account (illustrated with a sketch) of "My First Acquaintance with a Railway Accident."

Looking through a lot of small sketch illustrations of early locomotives

published in Engineer brought back to my memory some of my first ideas

of engines, and, among them, the little model I made at school, which was

as nearly as I remember as above.

[There is a drawing in the Diary.]

All the round parts I got turned by a turner in Sheffield,

to my own drawings, but these he did not follow, but his own fancy, hence

the hideous finish of the dome, etc. The boiler was a flat-sided box, with

a round cardboard top, to cover the motive power, which was a long Indian

rubber band, wound round the two rollers, and then round the driving-axle,

which one had to turn the reverse way to wind up.

I spent the whole of one Wednesday afternoon, a sunny one, too, puzzling

this machine out, as there was nothing to show which were fixed points. It

was no easy task. I fought it out, however, and was no end delighted with

the machine, and the 'wonderful way in which, by bringing one or the other

eccentric into gear, steam was put on either end of the piston, and the engine

made to go forward or backward. There was no lap then, and, I guess, little

or no lead.

This January to June term of 1841 I did more machinery than ever, in which

all my pocket money went. My special achievement was a locomotive on wood

wheels about 4 in. diameter, all parts turned in wood from my own sketches.

The motive power was got from a lot of Indian rubber bands stretched to and

fro along the boiler, ending in a string wound round the driving-wheel axle.

When wound up the machine could run the whole length of the big schoolroom

on a long form, about 120 ft. I ran alongside to guide it. It caused quite

a jurors among tbe boys, and I made contract with one of the masters

to make one for him like it.

In mechanical drawing I made a longitudinal view (part section) of a very

old-fashioned beam engine (Wall style). The shading was done in a sort of

blue grey, very blue. This was the crack mechanical drawing at the exhibition

of the pupils' work at the public examination at the end of the term. I was

made a fuss with, and had to stand out alone, and did not I hate it! Then

they gave me a diploma.

Walking home on our side the canal one evening at about five, I saw

the train which ran on the other side,. about ¼ mile off. The engine

ran off the line, and moving off to our side crossed the other rails, and

ran down the embankment, pulling part of the train with it. I was too tired

to go round by the lock gates and across the fields. But I went in the morning

to see the removing. There was no one hurt; my old uncle was in the train,

but was only bumped off the seat on to the floor.

There follow several entries bearing no reference to railway matters.

about May, 1842

It soon became evident that oil-crushing, etc., was not my vocation, and I was asked if I would like to be an engineer. And the authority set my chief friend, the millwright, John Kirk, to sound me, and to take me to see the engine works of Messrs. Fenton, Murray & Jackson, of Leeds. This happened one fine sunny afternoon—and all looked couleur de rose. There were several big locomotives building for the Great Western Railway, of the " Argus" (?) type—in all stages of completion. Of course I was caught, and on my return frankly admitted how much I had been delighted, and how I would like to be an engineer. As my next brother was just coming from school at the June holiday, it was soon arranged that he should take my place at the Oil Mills, and that I should go to "the foundry." Meanwhile a gentleman's son, who was an apprentice at the same works, was asked by the governor to supper to initiate me.

According to the Diary he did more, for Joy says "and he did," followed by "and he was a devil."

I was only a shop apprentice, as they took no others at Fenton, Murray

& Jackson's. I got four shillings per week, to rise as I got on, and

finally, I believe, to go into the office.

So one fine Monday morning I found myself at 8 a.m. at the foundry in fustian

clothes, like a working man. (Many a time after I met my father in the streets,

and he did not know me). That Monday I shall never forget, it quite disillusioned

me. I had to help a smith at the anvil holding things, and standing, standing,

oh! standing for ever. I got home somehow, never before so tired, dead tired,

but had to begin it again next morning at the place at six, after half an

hour's walk. Let me forget this now for ever.

However, I got accustomed to the "skinning," and then got at the interest

in the engines. These were Great Western Railway passenger— engines,

16 in. by 20 in. cylinder; 7 ft. wheel. They were a very handsome looking

engine, with bright brass dome, and wheel splashers—old fork and gab

motion— and I fitted one of these forks, having learnt to file and chip

and [he adds] to mash my knuckles with the hammer.

[Diagram 2 (not included herein) showed

type of locomotive under construction].

At this time all such work— fork ends of eccentrics, etc., was

done by hand, the forging was chipped and filed, and set to truth by a small

set-square; and a pair of callipers for outside measures, and below for inside.

Every fellow made his own in company's time, of course, and each fellow prided

himself on the high finish of his pocket tools.

August, 1842

After all the work of a day, I well remember staying over hours to

see one of these engines (the last) tried in steam. It was placed on special

rails with struts in front and behind, and the middle wheels resting dn

underground pillars, which they drive round, and to which was attached a

counter to show the revolutions per minute or the miles per hour. After that

test a dynamoineter was yoked on at the traihng buffer, and the hauling power

noted. Any way, now I was in my element, and happy, and I forgot to be tired.

The steam pressure was then only 60 lbs. —and no lap on the valve.

These engines finished, slack times began, and autumn and winter passed

very drearily away. There were three of us apprentices at the works, and,

being too far from home to return for meals, we fed in one of the workmen's

houses close by. Breakfast, 8 to 8.30; dinner, 12 to 1; afternoon tea, 4

to 4.30; works closing at 6 and opening at 6 a.m. Catering thus together

we did it for about 6s. 0d. per week. Saturday closing time was 4 p.m.

Here I had a slight accident to my finger, a big bar fell on it as I centred

it on the lathe, when it slipped. Then I was off for a week, and read

locomotives. Then the Chartists were making a row all over the country, and

came to Leeds to make demonstration and frighten folk. Of course I was a

working man, and yet a gentleman's son—so I had no bed of roses. At

Christmas the Governor at home got us a little organ to keep us at home,

and out of mischief ; more of that often. After Christmas we paid a visit

to Uncle Jack's at Manchester, and I went to see the shops of the Manchester

and Crewe Railway at Longsight, where Mr. Ramsbottom was then superintendent.

February 1843

All the engines I saw that I remember, were of the common type, same as Midland

Railway, and lots of "Sharps". Spring came, and times were slacker. Finally

Mr. Jackson sent for me to tell me that they were going to close the works,

so I should not be wanted.

Spring, 1843

Then I had a time of leisure, working partly at my foot-lathe, which

the Governor had given me, a 5 in. centre back gear on a wood gantry—cost

£5. Then reading hard at locomotives at home and at the Mechanics'

Institute, "Whishaw on Railways" especially, also drawing locomotives

—particulars of which I got by going to the railway station. My height

was then 5 ft. 6 in., and by that I measured the diameter of wheel, and then

made all the parts come relatively together.

The frontispiece in Whishaw was my friend the Great Western Railway engine

I worked at.

By summer it was arranged that I should go to Shepherd and Todd, Locomotive

Builders, Railway Foundry, as an office apprentice, paying £200 as premium,

and to work for nothing till I was 21—so I had not quite three years

of it to look to. Here, with vastly increased advantages, I just worked the

harder. Hours 9 to 5.30. and half an hour's walk home to dinner. The work

in the shop was only two of Gray's six-coupled goods engines for the Hull

and Selby Railway, fitted with "Gray's Patent Expansion

Valve Gear." Here was my fate again —" Valve gears."

At that time [Gray's gear was] the earliest example of expansion

working.

|

Autumn 1843

There were two other apprentices, W. E. Garrett, afterwards of steam pump

notoriety, and a I. Wright, son of a tailor, a tailor and a fool. I was at

once set by Mr. Todd (of blessed memory), to copy a longitudinal section

of one of these Gray's engines. The drawing I still have, with all the series

of elevation, plan, cross sections, etc Mr Todd taught us, and gave us every

chance We did shading, line shading, etc. We learnt all about the Gray

motion.

|

The locomotive illustrated in Diagram 5 had

90 lbs. steam pressure, and was fitted with the Gray

valve-gear.

I well remember the steam trial of this engine with its head just

pushed outside the shop door, the chimney just clear of it—the boiler

unlagged. The peculiar smell of a new engine floating about—they always

have it— and a little pother of hot, dry steam blowing bluish from the

safety valve. Steam pressure, 90 lb., the first lift from the usual 60 lbs.

So here I got my initiation into the use of higher pressure—I have seen

plenty of it since. The engine had the Gray gear. I at that time quite mastered

the dodge by which the lead was kept constant and the expansion got.

This class engine was the first to work steam expansively, and so to make

a saving of about 30 per cent. of the fuel.

Of various particulars and experiments with these engines I had a book full;

this was prigged by I.C.W. at Railway Foundry, but

one experiment remains.

The margin states that this book covers the period to 1841. The one experiment referred to is a comparative test between three locomotives, carried out on the Leeds and Manchester Railway, and occupied 5 days; viz., November 10th to 14th, 1840. The dimensions of the three engines are given as follows

GRAY'S PATENT: Cylinders, 11 in. (or 12 in.)

x 24 in. — wheels, 6 ft. and 3 ft. 6in. ; boiler, 9 ft. x 3 ft. 3 in;

weight, 14 tons ; firebox, 2ft.x3ft. 6in.; 94 tubes, 9ft. 6in.x 2in.

FENTON, MURRAY & JACKSON, ALTERED

Tubes, 436 ft.; box, 54 ft.—490 ft. ; grate, 7ft.

FENTON, MURRAY & JACKSON ORDINARY ENGINE: Cylinder, about 11 in.

x 18 in. wheel, 5 ft. ; boiler, 7 ft. 6 in. x 3 ft.

These are the particulars of the experiment

|

Autumn, 1843

Working through this [Gray] gear set me on scheming a reversing and expansion

gear of my own. This was afterwards re-invented by

Crampton and went by his name.

Here was my first attempt in the direction of invention of valve gears—but

I believe it was never used even by Crampton—but I remember drawing

it out and leaving it not locked up when I went to my dinner, and then

remembering it, rushing back, lest it should be pirated in my absence by

my sharp colleague in the office—not the tailor.

After this we began to get very slack, and once, on the occasion of a tracing

of a crank axle for a locomotive being wanted, we pupils quarrelled who was

to make it, so anxious were we to gct to a bit of practical work. Meanwhile

we were tracing everything we could lay our hands on for oursevies. And Mr.

Todd still taught us everything. As specimens my shaded locomotives, screw

and ball, mitre-wheel, etc., all in Indian ink shading. A Corinthian column

in line shading, etc.

June 1844

Mr. Todd came suddenly in to bid us good bye, leaving Mr. Shepherd

sole master. He soon brought a manager, Mr. Buckle, who had a son whom we

christened "Little Bottle," and we used to fight him. Buckle did not know

a word about locomotives, and was always talking about the big marine engines

he had had to do with in Russia, but he gave us a temporary taste for marine

engines.

This autumn [Aug. 14th] I got a holiday

to go to Wales, and on my way called at Crewe engine works, then the Grand

Junction Railway. I had an introduction from my father to

Mr. Trevithick, the chief engineer.

I spent the whole morning roaming round the works, and then made sketch of

the "Crewe Engine" thus (see Diagram

6 not featured herein).

Prior to November

1844

Meanwhile Mr. Buckle did nothing and left, and another manager came

from Manchester—I think from Fairbairn's—Dutton by name. He knew

nothing about locomotives, but got an order for a mill engine (beam, of course)

for Saddleworth. He made the general drawings himself, and we had to copy

out the details for the shop. It was a Fairbairn type, as I afterwards recognised

from drawings. All castings, columns, cylinder, valve pillar, and capitals

of Egyptian architecture. It was a clumsy looking beast.

December 1844

I was sent down to Manchester to the Leeds and Manchester Railway

works to trace some roof work for that railway, James Fenton being engineer.

This was a few weeks after the explosion of the "Ilk" [Irk] when she

blew out her firebox crown. Of course the box carrier crushed in, and flapped

down, and the engine was shot up into the air, and fell 150 yards away. I

got my work done in half the time the other fellow did (I. Wright), and fooled

about the works. Among other things I learnt was Mr.

Fenton's expansion gear, put on a six-coupled locomotive, the ''London.''

— I think I copied it on the sly; any way I got it. The reversal was

got by sliding the valve spindle link from one end of a lever to the other,

and lap and lead were arranged by slipping the eccentric (any one) round

on the crank shaft by the lateral motion of a screw.

Dates "are a little hazy", but it must have

been when "Link Motion" came out.At this time the general type of engine

for passenger trains was as Diagram 7 (not reproduced): but York & North

Midland Railway 2-2-2 with:

Driving wheels, 5 ft. 6 in. (or 6 ft.); leading and trailing, 3 ft.

6 in. ; centres about 10 ft. boiler, 8 ft. long, 3 ft. 4 in. diam. ; cylinders,

12 by 16 in., or 14 by 18 in. Steam pressure, 60 lbs., no weather boards,

and open railings round the footplate. Gab eccentric motion for reversing,

and no "lap" on valve. Rocking lever to valves which were on top of the

cylinders—sometimes a little round dome on the boiler, but mostly. a

big square dome rising on the firebox as in sketch.

In Diagram 8 (not herein) Joy illustrated a typical 0-4-2, goods locomotive with 'gab' motion.

Late in autumn I was sent on an outside job to Huddersfield via

the old Manchester and Leeds Railway. We travelled in open thirds, not

even a seat, but two rails, from end to end, and side to side—a pen

for sheep.

It must have been about then that the "Princess of Wales" appeared at York

Central station, where all new engines showed up.

This was a long boiler 'single' engine, but with inside cylinders, and the

valve chest between; the valve gear as per sketch

below,'[not reproduced] which I always thought

since was the origin of "link gear," but I had not seen it then.

Beyond my own information I give facts, from a letter from R. Stephenson

& Co., June 16th, 1891, kindly giving me the following information:

"First link gear put on their No. 359, delivered to Midland Railway, October

15th, 1842.

Wedge motion, H. S. & Co., No. 358, delivered to Midland Railway,

September 9th, 1842.'

This wedge motion, called Dodd's, I distinctly remember seeing at Masbro',

and the bridge, links, clamps, etc., then struck me as most

complicated.

Advent of Stephenson long-boiler engine

These had all the six wheels under the boiler. The most notorious

of them, the "White Horse of Kent," signalised herself by going off the road

repeatedly and killing a man or two.

This engine, with about 12 ft. boiler, all wheels under it, and cylinders

outside, further curtailing the wheel base, and adding to the overhanging

and disturbing weight, was a notorious roller, although just now rose the

cry for a low centre of gravity to get steadiness.

The " White Horse of Kent " is illustrated by Diagram 9 (in Rly Mag).

June 1844

The second Leeds Exhibition, under the management of the Mechanics' Institute,

was now held. The things I best remember were steel cutting (old files) by

a rapidly revolving soft iron disc; this gave a blaze of sparks and collected

a crowd. Then there was Furness's Locomotive, all in brass, with tubes and

a blast pipe. He was a chemist in Kirkgate, and we boys were in at the making

of this engine, spending hours in Furness's workshop. The engine ran round

lines laid in the figure of eight. He got up steam with a hand blast just

to move, and then the engine blast did the rest, till it ran as fast as he

dare let it go. It was a 1½ in. scale, of a 5 ft. 6 in. 'single' engine,

outside frame. Also there was a lovely model of the "Rocket" in brass, and

rather fancy in finish; this set me thinking that if I had time and patience

enough I could make one—but no!

In November, 1844, Shepherd brought round E.B. Wilson, of Hull, and soon

Wilson took the place, and went in for some patent spindle and fliers. I

spent all possible time at the old Leeds railway station, where guessing

the diameter of driving- wheel by standing by it (5 ft. 6 in. my height),

I proportioned the rest of the dimensions, so getting a fair outside view

of an engine.

January 1845

Joy mentions an order for ten engines for the

Manchester, Bury and Rossendale Railway.

Dutton, our manager, knew nothing of locomotives, so I had to take

all particulars from the railway's engineer, Mr. Cawbey, and I made all the

drawings of the engine, going to the station to copy details from Stephenson's

engines chiefly.

Mr. Cawbey was very particular about his water level and steam space, as

the engines had to work on an incline of 1 in 33.

Early in this spring [1845] Stephenson's "Great A" came out, and was the

engine which ran in the battle of the gauges against the Great Western Railway

engine " Ixion."

Apart from the general interest in locomotive

matters excited by the " Battle of the Gauges," these trials gave Joy his

first real ride on a locomotive:

We pupils used to frequent the railway station very much, and one

afternoon, watching the 4 p.m. York express start, the driver,

Sid. Watkins, asked me if I would like a ride. (Will

a duck swim? Rather). No coat, nothing on, I popped on to the engine, and

away we went, so jolly, This was my first fair run on an engine with a train;

only to Castleford, still it was fine. I had many another like it. And this

was "Great A" (see Diagram 10)

Vol. 22 Page 473-

Joy's accuracy and grasp of detail was recognised by his employers

August 1845

Was very busy now, though pupil, acting as chief draughtsman on the

drawings of Manchester, Bury and Rossendale engine, as I had to do everything

myself, picking up the information by copying the details from engines at

the station, chiefly from Stephenson's outside cylinder long-barrelled engine.

This type of engine had quite become the standard. for all passenger work.

(We had just got another manager, Alex. Wilson, who also knew nothing of

locomotives).

At this time we lads were always on the engines of the Y. &. N. Midland

Railway (as it then was called), taking little trips to Castleford, Milford,

and sometimes to York. And just now we got an order from this railway

for six engines—Thomas Carby, engineer. I had all these drawings to

make.

Joy presented his shaded drawings of this engine

to the local Mechanics' Institute. Joy illustrated the Y. & N. Midland

Railway locomotive No. 10 (not herein), with the following

dimensions:

Wheels four-coupled, 6 ft. diameter; cylinders, 15 in. by 20 in. boiler,

12 ft. by 3 ft. 4 in ; steam, 90 lbs.

This is the first I distinctly recall of the link gear, though our Manchester,

Bury and Rossendale engine had it on (but on the Manchester, Bury and Rossendale

engine it was the box link.) The next run I remember was with Joe Elliott,

on "Zetland," a little engine, like the Y. & N. Midland Railway engine,

but smaller——5 ft. 6 in. wheels.

At this time also I had to design a horizontal pumping engine for the Bramhope

Tunnel on the Leeds and Thirsk Railway, of which James Fenton was engineer;

for this engine I got great credit. And it afterwards became the drawing

on which Carrett, etc., etc., based their design for all their horizontal

engines.

With the four o'clock express from York we rushed into Leeds ticket platform.

With a hot big end the engine pulled up dead, and would not move till the

big end was slackened. We boys used constantly to get on the engines at the

ticket platform to run round the train, to push it in. All this autumn I

was at work finishing the Manchester, Bury and Rossendale Railway engines,

and the above Y. & N. Midland Railway engines.

January 1846

About now a new locomotive superintendent had come to Manchester on the Leeds

and Manchester Railway, and was to bring out a new type of engine, for which

we all looked out. She started three times from Manchester before she reached

Leeds, and she was a beast; nevertheless, she became the standard type of

the Leeds and Manchester engines (Diagram 11

not herein).

Now my apprenticeship drew to a close.

28 February

The first Manchester, Bury and Rossendale Railway engine was finished,

and we took her for a run to Normanton. A crowd of us was on the footplate

(Fenton was not named in my original tour at all) and all over her. Then

we had a big dinner at Normanton, and lots of wine. After having had a bottle,

or near it, I passed the bottle. And E. B. Wilson, to whom I sat next, said:

"Joy, you'll never make an engineer if you don't drink your bottle of wine."

I said: " I will, nevertheless." We all returned to Leeds on the engine,

being booked on to a Leeds and Manchester train.

There was not a sober man on the footplate but myself. The driver of the

Manchester and Leeds train not only made us pull the train, but he put on

his brake for mischief. Didn't our engine "spit fire!"

Went to Manchester with Manchester, Bury and Rossendale Railway engine with

Willis, taking the 9 a.m. train, and returned with her at night at 7 p.m.,

up Hunt's Bank without pilot, with a flame 3 ft. long from her chimney top.

Willis (the Black Devil), the shop foreman, with me.

3 March

My birthday and, free of my apprenticeship, had a spread at home.

Joy lost no time in seeking employment, for

next day he went to the Railway Foundry—

to ask for a berth. No, they wanted no paid hands. ToWilsons' at night

for a big dinner. Myers, the Russian, there. Twice as many bottles of wine

drunk as guests. A month later—on April

5th—he went to Manchester on executors' business, also to

seek a draughtsman's berth. Called at Leeds and Manchester Railway

offices—on

Sharpe<sic>, Roberts &

Co.—and others. No go. Stayed at Uncle John's. Home on Thursday, 6th,

and found a letter asking me to call at Railway Foundry. Went and found a

"break.up." Wilson out of it, and Fenton and Craven waiting. They offered

me a draughtsman's berth at 31s. 0d. (guinea and a half), took it and began,

disgusted. One engine to build like Manchester, Bury and Rossendale

Railway—-but with 5 ft. wheel. A drunken draughtsman (Archer) making

drawings exactly the same as Manchester, Bury and Rossendale Railway—but

only wheel dropped to suit rail-centre ; the line of cylinder the same!!

! I took up drawings and put them right. But that man could shade gloriously

even when he was drunk—so I learnt from him—I was not too

proud.

May 1846

Long boiler engines were going out; the engines did well, but were

bad rollers. One dreary afternoon the driver came, and said Mr. Carby wished

us to see them. Willis and I went, and left with the 4 p.m. express to York,

a wet afternoon with driving rain. (See the sketch, and see how much shelter

we got from the engine). And did not that engine tumble about. She rolled

like a ship in a gale. But we put balance weights on the wheels, and she

went all right then, and so did all the others when balanced. We were now

busy scheming engines for the Leeds and Dewsbury Railway, of which Jimmy

Fenton was boss, The only idea in favour was the Manchester, Bury and Rossendale

Railway engine, or some sort of long boiler—but we ended by putting

the cylinders outside, and the trailing wheels behind the firebox.

'While the goods engines had inside cylinders, and the trailing wheels behind

the firebox like the passenger. The type of engine designed for the Leeds

and Dewshury Railway, for passenger traffic, he describes as follows

The boiler was 11 ft, long, a sort of half-way to the long boiler type. The

goods were inside cylinders, six-coupled inside frames, cylinders below leading

axle; a bad engine, like Railway Foundry first lot of six-coupled for Great

Northern Railway. There should have been plenty of room for bearings, but

there was not. And the cry now was for low engines.

All this time I was working awfully hard, as the manager, Alex. B. Wilson,

knew nothing of locomotives, and that was all our work now. Autumn had come,

and our doctor said I must go from home to recruit .

So went with a party (Mr. Ripley, mother, and others), to London and Isle

of Wight. At Southampton met British Association, and went with them round

the Isle of Wight, Dr. Scores being of the party. Such a little tub of a

boat, but I knew nothing of marine engines then. Had a boat, and a plunge

and swim before breakfast. Back, after a fortnight, to Portsmouth with a

jolly rough sea. Home via Birmingham, where I saw a Norris's Yankee

engine at Bromsgrove.

Arriving at home on Friday night found a letter from Railway Foundry urging

me back to work.

30 November

So, on the Saturday morning went and found E. B. Wilson back in power.

I was to go same night to London and on to Brighton on Sunday to see

John Gray .about an order for ten engines, of which

I was to take all particulars.

Arrived at Brighton on Sunday night. Spent three weeks taking tracings all

day, and receiving instructions from Gray after 7 at night. He gave me an

engine pass, so I went all over the line on the various engines—to

Chichester on "Satellite," a little engine by Rennies (diagram 12

not herein).

Joy experienced one of several 'freak'

engines then around: Bodmer's four-piston balanced engine; the pistons

reciprocating were supposed to give balance. (Diagram 13 is a half-plan of

the motion) He rode on this engine from Brighton to Lewes, down the Falmer

Bank:-

Same engine, running hard, went off the road at same place a few years

after, and killed both driver and stoker.

Had a spin to London on one of the Gray engines, built by Hackworth to same

drawings I was taking.

On this trip we passed alongside of the old London and Croydon Atmospheric

Railway.

Anyway, the Gray engine could spin. Running through Clayton tunnel at 40

miles per hour she slipped, doubling that speed. I got my fill, too, of running

on long boiler engines on the St. Leonard's branch (Hastings was not open).

They did roll, and one went over a bridge into the river while I was there.

Returned to Leeds and started drawings for the new engines, 60—61 inclusive.

We had got the new drawing offices—over the entry— and Jimmy Fenton

for manager.

I had hardly started the Gray drawings when word came that Gray was 'out',

and we were to design a new engine. I, as chief draughtsman, had it to

do—so set off scheming by order of Fenton, of course, on the lines of

the last engine we had, Leeds and Dewsbury, short boiler (11 ft. 6 in.),

outside cylinders, drivers far back, trailing wheels behind the firebox,

and as much heating surface as possible in tubes, and 60 sq. ft. in firebox,

if possible. Got out 10 or 12 schemes in a week, and threw all aside—after

dissension. Then—12 noon, Saturday—Fenton came to me and said:

"Try another, and give inside cylinders 15 in. by 20 in., and 6 ft. wheels,

and again the biggest surface possible." I was sick of it, and bolted for

my Saturday afternoon.

Arrived at home, I thought over the engine to go for—and at once

it struck me what a pretty engine it would make. So abandoned the Leeds and

Dewsbury type, and all the feeling in favour of the long boiler class. This

was going back to the old engine, and my inoculation into Gray's ideas at

once biassed me in favour of that type. I had studied very well for three

weeks, and had ferretted among all the types of engines on the Brighton Railway,

and had ridden on most of them, with the idea to get a definite opinion of

my own which was best for big speeds.

So, having a sheet of double elephant mounted ready, as I mostly had now—as

I spent all my evenings at drawing any engine I could ever get outside dimensions

of—I set to work and drew out with Gray tendencies, a 10 ft. 6 in. boiler,

as big in diameter as I could get it, and as low down as I could possibly

get it—for the cry was one for low centres of gravity to secure steadiness,

though Gray did not seem to care for it. Cylinders, 15 in., by 20 in. ; drivers

single, and as far back as possible, 6 ft. diameter. Inside frames, which

must be made to carry the cylinders, the frames stopped at the firebox, so

that the firebox was got as wide as the wheels would allow it. This, of ordinary

length, gave 80 sq. ft. of surface, and with 124 tubes 2 in. diameter, gave

730 sq. ft, or a total of over 800 sq. ft. Then I put on the Gray's outside

frames for leading and trailing wheels, 4 ft. diameter, giving the bearings

below, thus making a firm wheel-base, with no overhanging weight.

Cylinders and valves between, with ordinary (then approved) link, but slung

only from one side. The steam dome on the middle of the boiler, and two safety

valves under a cover on the firebox. The fluted decoration of dome and valve

covers came in afterwards, and were a sort of combination of old London and

South-Western Railway domes and Gray's square boxes. So also the radially-barred

splasher for driver was a mixture of a lot of various engines.

On Monday morning I took my drawing to the Foundry (it is now in my possession),

and it was instantly and entirely approved, and I went to work on the details.

How these got strengthened up and thickened—the boiler and firebox

especially—I don't remember, but the total weights came out three tons

heavier than usual, and the engine itself as diagram 14.

This, then, was the origin of the engine afterwards called the "Jenny Lind," the type of the Leeds Railway Foundry engine, and I believe the first of the really steady fast runners and low coke burners.

In the Illustrated Interview with Mr. Archibald Sturrock, which appeared in the RAlLWAY MAGAZINE for August, 1907, Mr. Sturrock claimed that it was higher steam pressure that made his locomotives successful, and Joy ascribes the success of the "Jenny Lind" to the same cause.

Of course, it was the steam pressure that did it. But who was to blame, or to credit, for this lift of pressure from 80 or 90 to 120 lbs ? I have no note, but doubt not it was Jimmy Fenton. Thus this engine came out a mixture of the good points of the Gray, as first designed by Gray himself for the Brighton Railway, and the engine that had come of the long boiler, with its inside frame ; from this type it got the elastic plate frame, for leading and trailing wheels, but not rigid as in Gray's design. So these engines, at high speeds, always rolled softly, and did not jump and kick at a curve. Another thing which I think came of my fancy was a very free exhaust. I always, from the first, saw the blast port cores made, and with my own hands passed over them, had them passed over, to get a free passage.

end of 1846

In this new smiths' shop was one of the original Nasmyth's steam hammers,

with all its screws and tappets. Later

Joy designed and constructed steam hammers extensively.

It was under a general repair every Saturday afternoon, but it did

a lot of work.

May 1847

first Brighton engine, No. 60, was completed, boiler, etc., lagged

with mahogany. Made first run with her to Wakefield via Normanton,

and returning lost steam, and were nearly run into by the Manchester mail.

Opened new erecting and small tool shops with a big dinner and a ball to

follow, when Wilson brothers — Charles and Arthur— and I fraternised.

Charles is now head of the shipping firm Thos. Wilson & Sons, Hull.

First Brighton engine was called "Jenny Lind" after the famous singer, "Jenny

Lind," who was making a great excitement in London. I made a very highly

finished drawing 1 in. to 1 ft. of her (the engine, not Jenny), which was

lithographed, and sent about.

Got lots of orders here and there for this engine, and made at the rate of

one per week —then a vast accomplishment. Now arranged same engine for

a four.coupled.

Built the last Brighton engine, No. 69, with 6 ft. 3 in. drivers and 1,000

ft. surface.

Here I add an after thought which I had quite forgotten, of which I had no

record in either drawing or tracing like all the others; but of which I am

reminded by a picture in the Engineer, February 17th, 1897 which I

copy (see diagram 15 not

herein).

We were asked at Railway Foundry to build this engine, and I got out

a set of drawings for her, but when we got to the details of the vibrating

pistons in their cylinders, the packings for these showed very slight chance

of being made steam-tight, and E. B. Wilson & Co gave it up after I had

worked out the question to exhaustion, and the manufacture was taken up by

Messes. Thwaites Bros., of Bradford. It was patented by John Jones, of Bristol,

and called the "Cambrian"

system.[fully described in Sekon's

Evolution of the Steam Locomotive] Crampton's

patent locomotives were now coming to the front, and Joy early made their

acquaintance; indeed, that of the first—with 7 ft. wheels—built

by Tulk & Lay, Whitehaven.

She came to Leeds, and we ran a trip with her on the Midland Railway to Elkington

(Fenton was there) ; she had separate regulators for each cylinder, and one

rod being longer than the other, one shut off before the other, so she went

"dot and go one" when nearly shut off. She was awfully rough to ride on,

in spite of her very low centre of gravity, but we did. not know why then—I

do now. The furore for getting steadiness by low centre of gravity

and balanced parts was simply rampant. We built two Crampton's with 7 ft.

drivers.

Everyone was scheming on the above question, and at Railway Foundry we built a big coupled, which was called—to match with the "Jenny's"—"Lablache." Here we got perfect balance of parts, and a low centre of gravity with 7 ft. wheels, arranged, as in diagam 16.

Both these engines were the outcome of the cry for a steady engine

for high speeds, and the idea that a low centre of gravity was the only way

to get it.

In spite of this lower centre of boiler, the Crampton was a most uneasy engine,

and kicked at the curves, making her movement, when running fast, like a

series of rushes, to go off at a tangent, while the "Jenny" just swung to

the outside the curve, and the shock was taken up by her elastic horn plates.

As to "Lablache" her parts were in perfect balance, and we had a half size

model in iron in the drawing office set on tressels loose; this you

could turn round as fast as one could without disturbing its balance. The

engine had the credit of running 70 miles per hour as speed, and pulling

70 wagons (empty?) as hauling power. Indeed, it was told of her that her

driver, entering old Derby station with a very long train! saw red lights

to the left in front, and sent his stoker to see what they were, and found

them the tail lights of his own train. The curve entering Derby used to he

a short half circle (but still this must be American).

Anyway, this engine got sadly abused because it was thought too much of;

it was not even mechanically correct in its motions, as the paths passed

over by the two cranks were passed over at different instants of time. Thus

the main lever had to be made in two pieces bolted together by the big discs

in the centre, so that the two ends of the lever could move slightly

independently — to allow of the wheels passing round without skidding.

Again, to force her to pull big loads with her big wheels, the pressure valve

was screwed down regardless of safety. And one morning I had to go to examine

her in the Midland Railway Running Shed. I found the two top rows of firebox

stays drawn in sufficiently to make a rose of spray come from each. No wonder

that they brought her back to the station, saying, "she would not steam!"

If she had not got this relief, and damper, she would have blown her firebox

crown out, and killed every man of them. Next I examined the safety valve

balances, which were of the new fancy style with elliptical springs. They

were a bad gauge, as they were very hard and had little elasticity. Here

I found the balances screwed down till the springs were pressed fiat, and

the gauge stood at 220 lbs. if it had been worked, which however, it was

not beyond 120 lbs. I measured the rest. This was about the last of "Lablache";

she was afterwards reduced to a four-coupled "Jenny," and finished her brilliant

life as a ballast engine, sic transit gloria mundi.

In these wild days there was one driver specially

attached to Railway Foundry, one Jack Hemsworth, also called "Hell fire Dick,"

but he dare do anything, and was a splendid driver. He was one of the first

contract men—in the days when real coke saving was begun.

At this time the "Jenny" had become a very popular engine, and we were building

for very many railways as well as the Brighton, specially for the Midland,

and on this line it was decided to have a trial of a 6 ft. "Jenny" against

an ordinary Midland engine, and a type built by Sharpe <sic>, Roberts

& Co., and called the "Jenny Sharpe"

was chosen.

Sketch of the latter engine is given in diagram 17, whilst below are dimensions of both engines:-

By May, 1848. the "Jenny's" had become so popular, that the cry was not only for more, but larger; but Wilson and Fenton were very stiff as to alterations on the standard 800 ft. "Jenny," which was being turned out of that new long erecting shop with 12 pits— one a week it was now.

Even for the alteration of the position of a clack-box was demanded £5 to £25.

But the evolution of the locomotive was not to be prevented by such absurd disregard of the railways' requirements, for soon an enlarged "Jenny" came, with 1,000 ft. heating surface. Wheels 6 ft. 3 in. to 6 ft. 6 in., but only 15 x 20 in. cylinders; till the Manchester, Sheffield. and Lincolnshire Railway had the enlarged one built with oval boiler, 11 x 3 ft. 10 in. x 3 ft. 5 in.; heating surface: 169 tubes, 915 sq. ft. firebox 90 sq. ft.; total, 1,005 sq. ft.

| Ton | Cwt | Quarter | ||||||

| Weights | Leading | Right | 5 | 2 | 0 | |||

| loaded | Left | 5 | 1 | 0 | 10 | 3 | 0 | |

| Driving | Right | 4 | 1 | 2 | ||||

| Left | 4 | 2 | 0 | 8 | 3 | 2 | ||

| Trailing | Right | 3 | 10 | 2 | ||||

| Left | 3 | 10 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 2 | ||

| 25 | 7 | 0 |

This was according to the theory and practice of Brighton drivers, who said an engine would only save coke if you could spin her driving wheels round on dry rails, and that was why Crampton's were so extravagant, the wheels of which could not get round for jar.

May

1848

Joy went to London to see the lady after whom his locomotive was

named with someone—the initals in the Diary are "W. J."

Heard her in the Opera, Lucia de Lammermoor. Wonderful! lovely!

Amongst other things, he dined at E.B. Wilson's, in. Chester Terrace,

Hyde Park, where he met Peacock (Manchester and Sheffield), C. de Bergue,

etc., where it was arranged with Peacock to build ten engines, big "Jenny's."

"Settled particulars, and went down to Leeds on Monday—this was Saturday.

No contract in writing, only talk after dinner; still it was an order." Diagram

18 shows the engine.

Immediately after this a similar order was given by Mr. Kirtley, of

the Midland Railway, for 12 six-coupled goods engines with outside frames

and cylinders under the front axle, ,just to get a low centre of gravity,

but they were bad engines, the cylinders never seemed to be fast (diagram

19).

Most of these were built, but some of the boilers were difierently fitted.

Afterwards all this was reversed in a lot for Great Northern Railway, bearings

inside, cylinders over the front axle without regard to height of centre.

These big passenger engines were a splendid engine, with their ample surface,

but afterwards they got scattered all over, two to the Great Northern Railway,

where I once had a run on one of them from Retford to Doncaster in one minute

over the number of miles—that was 60 miles per hour all the way. Johnson

(pere 1) [possibly Mr. Richard

Johnson, afterwards the chief engineer of the Great Northern

Railway.] met us at the platform,

and shook his head at me, saying, "That's you, is it?" Well, we had run,

because I was there. I do remember that driver; he was killed afterwards

on that bit of road; going back over the carriages, a bridge caught him.

The consumption of these engines was

34 cwt., 30, 29, 25—114 cwt. for 560 miles=22.8 lbs. per mile,

whilst the distribution of weights was:

|

T | cwt | qrs | ||||

| Leading wheel | Right | 4 | 10 | 3 | |||

| Left | 4 | 3 | 0 | 8 | 13 | 3 | |

| Driving wheel | Right | 5 | 11 | 2 | |||

| Left | 5 | 13 | 2 | 11 | 5 | 0 | |

| Trailing wheel | Right | 2 | 4 | 0 | |||

| Left | 2 | 16 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 1 | |

| When empty | 24 | 19 | 0 |

December 1848

These halcyon days for engine builders did not to last for ever, for

in the collapse following the railway mania, the after-dinner orders were

repudiated, and so the Railway Foundry was left with about 20 engines far-on

towards completion. Joy tells the result in a few terse words

No orders, everything was to shut up, and I was to go in three months,

that is, March, 1849.

Spent spring at Railway Foundry finishing work just all under a cloud, and

this was very dreary after the lively times we had had with trying all sorts

of engines. In March I left, and looked after other work to no purpose, as

everyone was reducing establishments. So got a holiday, and a tour into the

English Lake district.

1 November 1849

E.B. Wilson sent for me in a big hurry to the Foundry. I was there

in the morning, and he wanted me to go to London the same evening to take

a lot of tracings, etc., for some iron work for "Baths and Wash-houses" in

Lambeth. "Engineering work" with a vengeance. I found it awfully hard after

our bright, brave, stirring locomotive work. But I was to stay in town after

as the "London Agent of the Railway Foundry Company."

And I was established in a big house as offices—No. 19, Great George

Street, Westminster. (I stayed here till March 5th, 1850).

Shortly after the offices were opened, Wilson came up to stay, and brought

his wife, then it was awfully gay, or busy work.

Joy now came in contact with many of the leading

railway engineers. Every Tuesday evening he and Wilson, went to the Civil

Engineers' Institute,

and, after that, always four or six big swells in with us to smoke

and talk. I remember John Fowler, Bidder, Stileman, Maclean, the Stephenson

then to the fore [Robert], and C. P. Rooney (Cusack Patrick R., afterwards

Sir C.P.R), secretary of the Eastern Counties Railway. Wilson was a very

energetic and daring man, and so we were all this winter full of schemes.

One was for our taking a section of the Eastern Counties Railway and working

it by contract, finding all material, coke, etc., and paying all wages, taking

over a selected lot of the railway's engines. With this view we had heaps

of meetings with the chairman, Mr. Betts, and C. P. Rooney. And always these

meetings had a appearance of secrecy, and were really one part of the Board

wqrking in opposition to the other.

Joy was again in his element, for he had to

inspect all parts of the Eastern Counties Railway and the various conditions

obtaining, to do which he had to go spinning all over the line on the

engines,

much to my delight, and always with a sort of mystery about it all.

Also we got bold of a lot of Eastern Counties Railway engines, long boilers,

so recently in favour, to alter them into four-coupled "Jennys," cutting

their boilers down to 11 ft., and putting the trailing wheels behind the

firebox, and their cylinders inside ; yet with 2 ft. 0 in. to 3 ft. cut off

their boilers and tubes, they steamed better.

Then came the furore for light trains to carry the least possible

tare weight. This came of the crash among the railways in the autumn of 1848,

and forwards.

Samuel, on the Eastern Counties Railway, was working on this line, and had

two small engines running, the "Enfield" and the

"Cambridge." This question of "light locomotives" I had to examine. Short

notes of some of these runs are

"Enfield," December 10th, 1849: 7 cwt coke: 78 miles, 6 hours in steam=10

lbs. per mile; at 45 miles per hour, sleet and mist, rails greasy.

December 11th, ran half miles in 45—44, 42—40 sec=45 miles per

hour.

Cambridge ran ½ mile in 54 secs.—53 miles per hour.

Cambridge to London, 57½ miles, 7 cwt. coke 13.6 lbs. per mile, cylinders,

8 in. x 12 in. ; wheel, 4 ft. 9 in., leading, 2ft. 8 in; boiler, 6 ft. 6

in. x 2 ft. 9in. ; tubes, 112, 7 ft. x 13/8in., outside cylinders, inside

framed, Cramptons bearings. The "Cambridge" is illustrated by Diagram 20

(not herein).

January 1850

Working in Great George Street, Joy schemed

light engines with London and South - Western engines partly as type—but

inside cylinders — bulging the boiler in, where it was in the path of

the crank, to get a low centre of gravity. Also the question of increasing

pressures to get bigger powers out of smaller engines attracted his attention.

Out of this scheming he got at his first idea of the double boiler, making

the boiler in two, so that lighter, thinner plates would do.

Mixed with all this was the cry for steadiness now called for in another

form, and I worked up the question, and spoke at Arts'

Society. It was jolly, for I knew my subject. I compared the "long boiler

" with its short centres, and heavy overhanging weights at each end with

the "Jenny Lind" with the weights mostly within the centres.

I also went into the effect of inside or outside bearings, but this is only

a question of elasticity, as the wheel tread is the real base.

Worked on at double boiler in a new form as a coupled engine. This tracing

I lent to someone and lost, but I remember it well enough, with the particulars

from my note book, to reproduce it.

This engine was then built at Railway Foundry as an experimental one, but

this came after.

Meanwhile E. B. Wilson agreed with me to patent it, jointly, he finding the

cash.

This initial patent of David Joy's was the means of introducing him to Brunel, for Wilson took Joy with him to show it to Brunel. Joy's time was now spent at the various offices of the railways, seeking orders for engines, wheels, anything; the evenings were spent in estimating costs with E. B. Wilson.

Then came Easter, and I went back to Railway Foundry. This proved a permanent move, but before I left town there was the first fuss about the proposed International Exhibition. Wilson was very full of it.

On return to Leeds Joy

records

worked in a very desultory way in the office. Wilson came home with

an order for ten Great Northern Railway goods engines, and telling Dickenson,

the cashier, the price, Dickenson said, "Why, Mr. Wilson, that will only

pay for the engines." Wilson swore a big oath, "D—— I never counted

for the tenders at all."

Sturrock (Archie) was then the new locomotive superintendent on Great Northern

Railway.

These engines were just about copies of the Leeds and Dewsbury's inside

cylinders. Wheels behind box; they were beasts, but I don't know why—they

were crowded in all their bearings. I think it was now the new drawings of

"Double Boiler" we got out.

END of V. 22

23: pages 39-48

May 1850

Joy was becoming more appreciated by the Wilsons as shown by staff changes at the Railway Foundry

A great "dust up" was in the shops, the shop foreman, Bob Willis,

alias the "Black Devil," was kicked out, and Wilson put me in. It

was horrid hard work, back again to 6 am. to 6 p.m., and not a moment's respite.

Now we got another order from Great Northern Railway for 10 four-coupled

passenger engines, 6 ft. wheels. These I sketch because they became quite

a type, and were the back stay for the running of the passenger trains, and

all the specials of the Exhibition time the following year.

It is interesting to read the views of these engines as expressed by Joy, and also by the designer. What Mr. Sturrock claims for the design can be read by reference to the R4ILWAY MAGAZINE for August, 1907 (p. 92). Joy summed them up:—

There was Great Western Railway go in them, Sturrock's stamp, but they were a one-speed engine, yet always ready for their work. My No. 266, on the Nottingham and Grantham Railway, was one of them built for a contractor with 5 ft. wheels.

One of these engines is illustrated by Diagram 22.

Joy inserted remarks about the limitations placed

upon the designers of express locomotives

In the big struggle to enlarge engines, the 'spread' had to go every

way, and there was an objection to it every way. Thus:—

She must not be longer, she would jam the curves.

She must not be wider, she could not pass the platforms.

She must not be taller, she would topple over.

We shall see how even tually all these difficulties were got-over, or were

found not to be objections, but some of them advantages. These were some

of the largest engines of the day:—

| ft | in | ||

| Crampton's French | 16 | 0 | extreme couplings [? Wheel Base] |

| "Lablache" | 16 | 0 | |

| McConnell's "Bloomer" | 17 | 0 | |

| McConnell's Patent | 16 | 10 | |

| Crampton's "Liverpool" | 18 | 6 | |

| Great Western Railway "Iron Duke" | 18 | 6 | |

| Stephenson's "A" by McConnell | 19 | 0 | |

| Stephenson's "A" 8 wheels | 19 | 0 | |

| Great Western Railway South Wales Tank | 17 | 0 | |

| Great Western Railway Bogie Tank | 22 | 6 | |

| Hawthorn's Bogie engine for Great Northern Railway, 1851 Exhibition | 22 | 6 |

June 1850

Quarrelled with E. B. Wilson about forthcoming Exhibition for 1851,

and went at a moment's notice, J.C. Wilson taking my place as shop foreman,

and prigging my books and papers in the shop foreman's office—all my

John Gray's notes.

Summer, again a holiday.

August 1850

E. B. Wilson fetched me on a Friday evening in a cab, took me to

Arthington Hall to go next evening to open Nottingham and Grantham Railway

on the Monday. He had taken it to work by contract at 2s. per mile run. No

engines, nothing ready.

To Nottingham early Saturday. Midland Railway supplied us with two old Bury's

singles to be at Grantham Sunday night. Saturday afternoon over the line

with Underwood (engineer), Gough (secretary), and on the contractor's (G.

Wythes) engine (ballast), went off the road, not very fast, but a jolly tumble

about. Water tanks all to get ready by Monday.

Then came the opening.

Started at 9 a.m. with first train—five or six carriages—part second and third—and a lot of low-sided wagons.

Joy gave the following statistics of the coke consumption for the "Bury" engines he used for working the Nottingham and Grantham Railway upon its opening, running passenger and a few goods trains

| No. 107 did 18 trips Express three carriages No. 115 ditto mixed traffic |

409½ miles 91 388 4277 |

4 tons 10 cwt. coke 1 tons 0 cwt coke 4 tons 10 cwt. coke 54 tons 0 cwt coke |

= 24½ lbs. per mile =22½ =26 =28 |

So I got my first experience of working locomotives with old Bury's

engines.

Joy soon found that theoretical locomotive

engineering was not quite the same as practical, but his assurance carried

him through successfully. He says

I saw my first piston "set up," and told the man to do it, watching him, and suggesting just as if I knew all about it.

Here, too, I had my first go in at driving. I took No. 115 and a "cleaner

"—not a stoker —and about seven wagons of goods, and stuck fast

four miles out—short of steam, hut I did not let the cleaner know that,

but had to adjust something (that was the apparent cause of stopping) till

steam got up, and then I never did it again. But these engines without "lap"

and without expansion could not be humoured any way. I could drive after

that. In those days the "hook in the chimney," as it was called, was the

refuge for the destitute.

In those days railway traffic was worked

in a very haphazard manner. Even primitive signalling had not then been

introduced. Joy soon has his first escape from death by a railway

accident

We had got another engine from Railway Foundry, known as No. 266,

and she did "goods"; and Nottingham Goose Fair coming, and a special ordered

for Nottingham, I snapped at the chance of driving one of the engines. I

don't know how it all came about, but at night I found myself on the leading

engine, the other old Bury behind with old Pilkington as driver down at the

junction of the Mansfield line at the front of a long line of carriages,

on the down main line, which, for the day, was being used to stand lines

of trains—the down trains for Mansfield being shunted at the junction

on to the up line to the next station. It was pitch dark; and we waited for

a signal to go on to Nottinghem with our train, and waited long. At last

a rustle, and I thought we were going to be liberated by the passing out

of the mail to Derby. So watched for her disappearing sideways to the right,

but no, I could see her sweeping round and approaching us. And instantly

I calculated that she could not have stopped and passed on to the up line

at the junction, so must be on our line rushing upon us. It was not many

seconds before we found all this true, as we jumped from our engines and

rushed forward on the "in" side of the curve, and only just in time, for

I saw the flare of the ashpan of the coming engine ripple over the sleepers

as she came on, and heard the broken buffers of my own engine wizz over my

head. It was only just in time, the next instant our two poor little light

Bury engines were one wreck of material in front of the big six-coupled,

with a train of twenty crammed carriages behind her.

The footplate of my engine disappeared entirely, the firebox of the engine

falling in between the legs of the tank—buffers and buffer beams gone

altogether. It was an awful experience, and none of us forgot it in a hurry.

After this 'spread' (as Joy calls the accident)

of October, 1850, more engines were wanted for the Nottingham and Grantham

Railway. These the Midland Railway provided, and Joy remarks

I don't remember both, but one was a little "Sharp."

This little engine was nearly the death of a nephew of one of my directors.

He wanted to ride with me on the footplate one night with a special I said,

No! We ran down Biugham Bank into a fog—stuck—no weather board.

Suddenly we went through the road crossing gates, the bits flew all round

us, we knew how to duck.

As Locomotive Superintendent, Joy found that he had to execute his repairs at Grantham under difficulties; but he says

Still I had the wagon building works of Neal, Wilson & Go., of Grantham, to go to, and material from Leeds. Still running repairs we did. Thus, setting up worn piston rings was done by hammering the middle of the ring with a ball-faced hammer. I soon did this quite as well as a fitter—the hammering was most in the middle, and eased off towards the end, so the ring could be made to swell out in a perfect circle.

Here is a glimpse of the wonder with which country people regarded a railway in the 1850s

One of the funs of the place was its being a new line, everybody and

everything was strange to the engines.

People used to come and get on to the line at the road crossing gates

and wave their umbrellas at us to stop as if we were an old stage coach:

We didn't.

Then the game, and cows and sheep used to stare. We picked up lots of game,

especially at night, when they ran at the lights.

George Stephenson's coo was soon in evidence on the Nottingham and Grantham Railway, but she did not live to repeat the experiment.

She was the property of the navvies, and was considered free of the

Line, but she did it once too often. We were running at Ratdiff Bank from

Nottingham with a train of coal, 15 wagons, and the old thing was going to

cross the line; the driver thought he would get there first, and outrun her,

and kept on steam; suddenly she ported her helm, and came diagonally on,

and the next instant the buffer beam caught her buttock beam and toppled

her over and went clean over her, her body tumbling through the whole train,

some times under and sometimes over the axles. I was in the van, and watched

the wave on the wagons as we passed over her, expecting every moment to see

the train separate and roll off.

We stopped and tippled her off the line, and I don't think there was a whole

bone in her body.

Locomotives of the early 1850s had little or

no reserve of power:

The Ratcliff Bank was a bother, as it started in 1 in 110 up, and

went into 1 in 130 and 1 in 176—so we often had a stick on it with a

load of goods even when we had taken a big run at it from the level at the

bottom. Then the englne would puff out her last breath till she stuck dead,

Then we put oil the brake at the back, and spragged the last two or three

wagons, and then backed the engine close up with every buffer compressed

or close, and every drag chain slack; then at the given moment on went steam

full, and the engine would pluck wagon after wagon on till the last was caught

up, and at a slow pace we would move on a bit to stick again, and repeat

the dodge till we topped the hill, and then run merrily down to Bingham—1

in 76.

Anyway, this life was very lively, and I learnt every practical dodge going,

and could drive as well as a driver, indeed better. Thus, I caught one of

my drivers alone on the engine one night at Ratcliff, his stoker had gone

to prig coal to whip up the fire, which was dead, and the steam slack. I

felt I must do the moral thing, so sent the coal back, and told the man I

would take the engine. Well, somehow or other, I wheedled her, got steam

up, crawled through the tunnel, and, that over [the summit], slipped down

the bank to Grantham like anything, and then told the man, "Do that next

time." But I did win those fellows to care for me, and to believe in me.

I had one very clever fellow from Brighton, Bob Wilkes. I learnt heaps from

him.

By October the Nottingham and Grantham Railway had got the four-coupled

engine (No. 266, previously referred to), which was one of the Great Northern

Railway's passenger, built with 5 ft. coupled wheels; cylinders, 16 in. by

22 in. ; wheels, four- coupled, 5 ft. diameter; about 1,100 ft. of heating

surface. No dome, only slotted steam collecting pipe. Weight, loaded, 26

tons ; light, 23 tons 14 cwt.

Cost of one week's running goods trains with No. 266

Before this (September) we had a big special to Matlock, and borrowed of the Midland Railway a big six-coupled engine, built by the Railway Foundry. This engine worked the train, and back to Grantham as a trial, to see if she would suit our work; anyway she was accepted by the company to add to the plant, her No. was 158 (see diagram 19, not included). Her weight loaded, was 28 tons 9 cwt. 3 qrs. -light, 25 tons 14 cwt. 1 qr.

Before the end of 1850 the two new "Crampton" passenger engines came from Railway Foundry, they were called the "Little Mails," another went to Darlington. They were credited to W.E. Carrett as his design, as the double boilers had been to me.

Joy's drivers were unused to the link gear,

and as the ' Little Mails' were fitted with it — Joy remarks:—

What a mess the driver, old Pilkington, made of his first trip. I

knew right enough about driving, with link gear and expansion, and told him

after starting to pull her up on the link, but he would not believe she would

pull, and let her out, to stick fast at Elton, three stations on. Then I

made him link her up.

They were smart little engines, as can be seen from diagram No. 24, which is a drawing of Grantham.

These two little engines were called "Grantham" and "Rutland," and were supposed to be alike, but" Grantham" had brass tubes, and "Rutland" had steel tubes, and was somehow different, always giving more trouble, not so smart, and burning 1 lb. coke more per mile.

Several pages of the diaries are filled with details of the running of various trips by these engines, the maximum speed being 66 miles an hour, attained by "Grantham," with two coaches [weighing together 11 tons down the 1 in 165 bank near Bottesford.

The rolling stock, locomotives, etc., were the

property of E. B. Wilson & Co., who worked the line by

contract

Total capital and plant on Nottingham and Grantham

Railway:—

| Cost each | Total | ||

| 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 1 2 |

Low sided goods wagons .. 11 in. cylinder locomotives .. First-class carriages .. .. Composite ,, .. .. Second-class ,, .. .. Open tbird'class,, Parliamentary .. Wood framed goods van .. Horse-boxes |

63 1,100 295 270 200 125 160 80 100 |

630 2,200 590 540 400 250 320 80 200 |

| 10 25 5 1 |

Cattle trucks High sided covered low wagons High sided, uncovered. Iron carriage truck |

75 80 70 50 |

750 2,000 350 50 |

| 1 1 2 1 1 |

6 coupled engine, No. 158 .. 4 ditto No. 266 .. Iron guards' vans .. .. England's screw jacks .. .. Lamps, couplings, etc 11 in. cylinder tank engine .. |

2,000 2,000 120 20 — — |

2,000 2,000 240 40 30 1,300 |

| Total | £14,000 |

5 per cent, on £14,000=£700=£55 6s. 8d. per month.

£58 6s. 8d. per month on 5,820 miles=2.40d. per mile run.

There was afterwards added an odd Jenny Lind.

April, 1851

The next entry in the diary records Joy's visit

to Leeds to the trial of the double-boiler locomotive. He first took her

to Leeds and Bradford to work trains against those drawn by "Jennys"; the

comparative dimensions of the engines were

| 'Jenny" | cylinders | 15 in. x20 in | driving wheels | 6 ft | heating surface | 800 ft | 24 tons 1 cwt |

| Double boiler | l2 in. x 18 in. | 5 ft | 750 ft. |

Of these competitive trials, and referring to the running of the double-boiler engine, he says

The trains consisted of about ten ordinary carriages, say, 60 tons. Kept time fairly. Then went to Normanton to let her fly. In those days an engine could not go too fast for me.

But judging from the table below, the weight of the engine was very unevenly distributed. Joy soon had these altered, so that there was about 3¼ tons on each wheel.

| T | cwt | qrs | ||

| Weight on wheels | Left hand leading | 1 | 12 | 0 |

| Right hand leading | 2 | 11 | 2 | |

| Left hand driving | 4 | 10 | 0 | |

| Right hand driving | 4 | 5 | 2 | |

| Left hand trailing | 3 | 13 | 0 | |

| Right hand trailing | 3 | 1 | 0 | |

| Total | 19 | 13 | 0 |

Then she went back to the works to be decorated for the Exhibition.

Back to Nottingham, took a tour among the collieries with one James Smith,

a small engineer, but a gentleman. Among other things had a thorough go on

one of the American engines by Norris that came over to England in 1846,

which I saw at Bromsgrove (see diagram 26).

This engine was then doing contractor's work. I had seen these engines at

first arrival at Bromsgrove.{on my London and Isle of Wight trip in

1846}

Joy now had an opportunity of testing one of these American engines which had been imported by the Birmingham and Gloucester Railway.

The little thing could pull, but she was odd, plenty of cast iron

in her, even the cross- head pins were cast iron.

1 May 1851

Went to great 1851 Exhibition, for which I had a season ticket. It

was a grand sight, but what gave one an idea of its size was that, as H.M.

the Queen and procession passed up the nave, one could see the shaking of

hats, etc., but no whisper reached one for long, and then it came on like

a wave. And I knew they could tune one organ while another was playing full

organ in another part of the building.

The locomotive department fetched me. There were the Great Western Railway

"Lord of the Isles," or "Iron Duke"; "Lady of the Lake," London and North-Western

Railway— the 'double boiler,' painted blue, and looking lovely; an "Ariel"

by Kitson's, which went afterwards to North-Eastern Railway at Thirsk, also

painted blue.

Joy next relates his experience on the locomotive with a premium pupil

Returning to Nottingham, I got on the engine, and found my gentleman driver there. He had come to Grantham to learn all about locomotives, driving also, as he was going out to India to take charge of a railway, and wanted to know all; he was what the drivers called a "well plucked 'un."

Getting on to the engine, I found she literally jumped under steam—she just was smart enough to make me look round, and say, "What's up?" There was no steam blowing off, but I felt the valve, and then looked at the markings on the balance—we had not gauges then as now. I just was astonished to find it registered 220 lbs.. Godfrey Mann said, "Oh, he thought it was all right, the engine was very jolly." I quietly let "her down a peg," not that I was afraid. I knew her strength.

Joy here illustrates in the diaries one of the Great Northern Railway's 6-coupled goods engines then being constructed at the Railway Foundry. Of these he says

I did not get one of these engines, they were too good for us, we only got one of those old lot with boilers same as the Manchester, Shef field and Lincolnshire Railway's big "Jennys," the cylinders being below the leading axle, 17 in. by 24 in.'— a low sort of engine.

In the autumn we were arranging to transfer the contract to work to Neal & Wilson, of Grantham, and this terminated October, 1851, and the company added to the plant another engine, an odd "Jenny" from the Railway Foundry.

I had a very hard time settling up, but got some nice runs in the country to Bottesford for Belvoir Castle, and the Mausoleum, to Preston to see Newton's birthplace and the tree from which the apple fell!

October 1851

Free from Grantham, looked out for something else.

North British Railway asked for a loco superintendent,

so I hunted up all the testimonials I could muster, and set off one miserable

January afternoon to Glasgow, spent about a fortnight seeing directors and

officials, getting testimonials printed, etc., then sent in all, and in a

few days learnt that there had been 150 applications, and I was one of three

for a further consultation. Missed it after all. They said "I looked too

young "—so I did, but I knew enough. Then I got ill. When better I stayed

with some friends. Went to see Professor Nichol at the Glasgow Observatory.

He showed me all over—his big reflector especially — 24 in. speculum,

20 ft. focal length—I consulted with him as to a reflector I had thought

to make, 6 in. speculum, 6 ft. focal length. He said I could make 8 in. x

8 ft. quite as easily.

Home to Leeds and spent my winter drawing designs for locos. with the "Jenny"

as my type, and with a very strong conviction that quitting the steam quickly

was the way to get both speed and economy.

12 January 1852

He refers to a drawing of a single engine 'dated January 12th, 1852, which he made, and also shows a valve, of which he writes:

This was the valve with a double exhaust port. Dimensions of engine as below:—

| Cylinder | 15 in x 20 in |

| Blast pipe | 5¾ in |

| Wheels (diameter) | 6 ft in and 4 ft |

| Coupling | 14 ft 11 in |

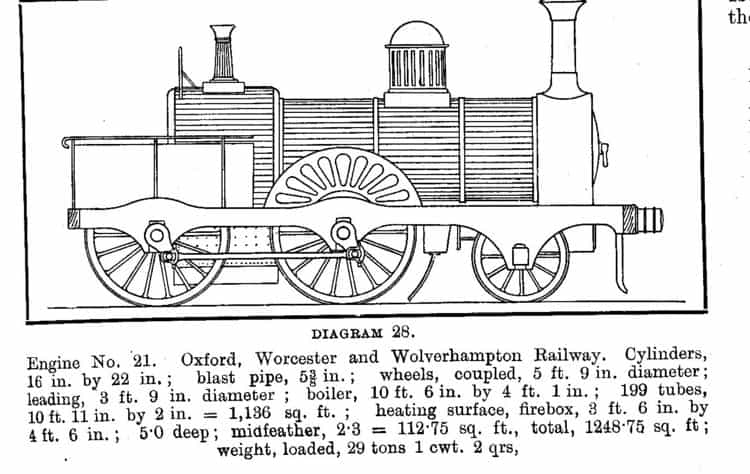

| Boiler (length) | 11 ft |