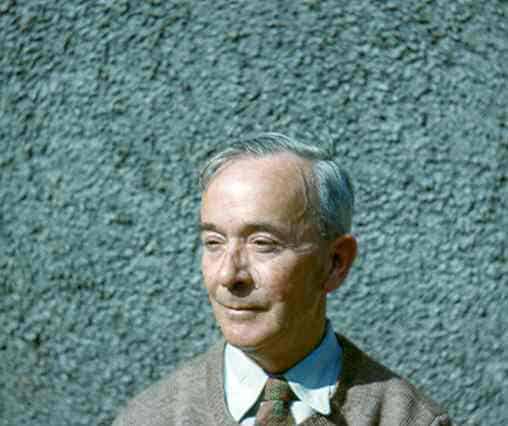

| Frank Jones |  |

| Frank Jones |  |

Kevin P. Jones

At the suggestion of Geoffrey Hughes, I am placing this incomplete file on the Internet until such time, if any, that it is possible to publish it more formally. It must be stressed that this account is far from complete but not much more awaits attention in the loft in West Runton and in my father's diaries located in a flood-prone garage in Cornwall!. A letter from 1953 flluttered down from the loft in March 2019 which has slightly improved the story.

My father, Francis (Frank) Lovett Jones was born in Dundee on 12 May 1901 in South Tay Street. As is self-evident from the name, neither of his parents were Dundonians, (Ernest Jones was born in Chester and his wife in Liverpool of parents from the west of Ireland) and my grandfather had no direct connection with the railway industry, but sometime during the First World War when my grandfather's income from teaching music was suffering from the effects of the War, my father was forced to leave school and start work on the North British Railway at Tay Bridge station: the Dundee Courier and Advertiser (13 August 1955) noting his return to Scotland recorded that he started work in the district traffic superintendent's office in 1916. This was always a source of resentment to my father whose three bothers and two sisters had enjoyed, or were to enjoy, some form of further education. After the War when my grandfather's income recovered my father was offered the possibility of going on to university, but this was declined. It is strange to think that he was probably involved in some way in the special traffic arrangements described by Alistair Nisbet in BackTrack 14 p. 194. He certainly worked with people who had been on duty on the night of the Tay Bridge disaster. Although my father was to try for a place as a traffic apprentice on the LNER his application was unsuccessful and this tended to colour his view towards the railway industry, and possibly towards some of those who had been fortunate to follow this favoured route towards becoming a railway officer. My father was never a railway enthusiast and he thoroughly disapproved of his son's activity in this connection, especially anything to do with the numbers on locomotives. As a young man he became interested in golf and First Aid, and studied for examinations (at St Andrews University on railway economics) and left dull books on railway accounting, etc.

|

Frank is on left on his Father Ernest's knee: eldest child Mary behind |

It is not clear to me when my father became involved in public relations work (see end of page for Sir John Elliot's introduction of this concept to the railways of Britain), as distinct from advertising. He left Scotland for London to get married in the early 1930s. He moved to the Advertising Manager's Commercial Advertising Department of the LNER at Marylebone. He was probably working for Dandridge at the outbreak of the Second World War and was living in Bexleyheath to be near my grandmother who lived in Charlton. Originally they had lived in rented properties in Kenton and Eastcote to be near Marylebone, and had contemplated house purchase in Chorley Wood, but strangely ended up in Bexleyheath. During the War the office was moved north to Hadley Wood and we moved to Potters Bar where my sister was born in 1941 (died 26 December 2005). It is clear from Diary entries from much later that he had never liked work in advertising.

They had been moved there from London and were in effect redundant as advertising was in short demand except for propoganda. In fact during an interview he was told that now the waste of paper was banned Mr Dandridge the Advertising Manager was redundant to requirements which Dad said would be news to him. The only thing you were allowed to use paper for was to light the fire but there were dire threats against using it to wrap left over food etc. When refused more pay he applied for the Station Master's position at Roydon, but was unsuccessful. He turned down a move to the Goods Division and requested a move back to Scotland on health grounds. James Ness the Divisional General Managers Asst said he could place "Jones somewhere in Scotland". My father's response [Diary 7 August 1942]: I called to see the Chief Clerk late this afternoon and showed me a letter from James Ness [KPJ as my father used "James" he must have known him from NBR/LNER days in Scotland, which may influence later events] saying "I do not anticipate any difficulty in placing Jones somewhere in Scotland". There is something significant in the phrase "somewhere in Scotland" that I care not for overmuch. Scotland is extensive & has Districts in which I would not care to live. On the previous day [6 August 1942] he had noted "The children's environment, outlook, pronunciation will be altered". [KPJ has never regretted that initial introduction to Scotland at the age of seven, and by the time he left for the first time was sufficiently "Scottish" to rejoice in the nickname of MacTavish].

Subsequently Diary entries include: [17 August] expenses limited to three months; [18 August advised to travel to see Mr Dunlop]; [19 August] "Saw Mr White (presumably man who was, or was to become, Advertising Manager: see Steam Wld, 218, 56.) and Mr N. Francis together this morning" (presumably one was Chief Clerk). Prior to this he had noted [9 July] "Typists asked to indicate whether any would like a change of work to another Department to faciltate travelling or for any other reason. 3 of them elected to go. It is rumoured the Department may be closed down" and 30 July "There has been a heavy falling off of the amount of work to do at Hadley Wood, where I imagine, I will not remain much longer. The article in Steam World No. 228 pp. 36-7 by Andrew Dow's on his father's paper schemes for cross-London railway routes, published in The Star on 14 June 1941 are probably indicative of this sense of "nothing-to-do" at that time..

At this point it is worth noting that my father's diaries were sporadic and that there were none written during the Edinburgh years. I suspect that Dunlop's first name was "James" and I know that he lived in Corstorphine, near to the tram terminus in a typical Scottish detached bungalow. We lived in Slateford (41 Allen Park Crescent) in a rented semi-detached bungalow within earshot of the LMS marshalling yards across the sports fields. My father travelled to work by the Edinburgh Suburban Railway from Craiglockhart Station reached by crossing Meggetland. He was in the Home Guard.

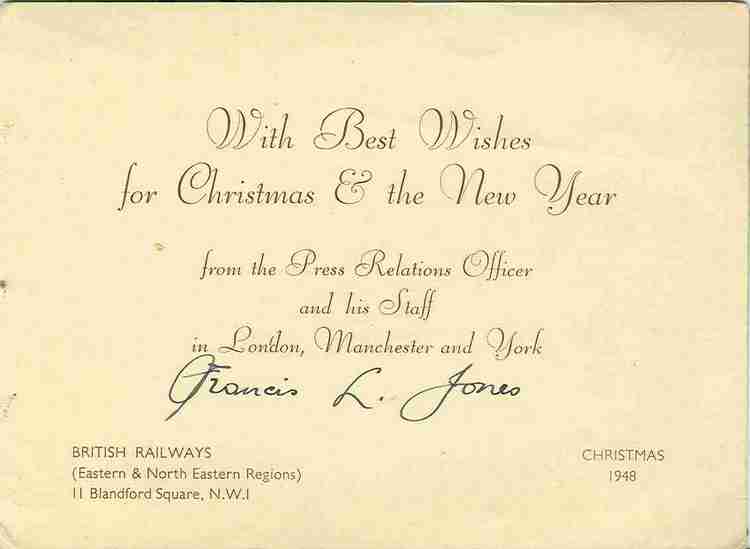

In a letter written to George Dow on 9 March 1953 concerning a possible move to Liverpool Street Frank wrote: "I took charge of the Press Office, when my close contact with Chief Officers, District Officers and the Scottish newspapers afforded invaluable training. I went up to London in 1946 to take up a position in the Press Officer's department of the Chirf General Manager of the L.N.E.R. and was appointed Press Relations Representative, Manchester (Eastern Region) in 1948. PPromoted to the position of District Public Relations and Publicity Representative, London Midland Region Manchester 1950, I have worked closely with the Divisional and District Officers in the Manchester district." The post being sought was not in Dow's then area of expertise, but in a development section of the Commercial Superintendent's Departmen: hence the style of writing. Nevertheless, it does give titles for his pre-Glasgow career.

KPJ has not discovered Dunlop's official job description, but Frank was ckearly in charge of the Press Office in Edinburgh during the latter part of World War 2. KPJ also assumes that it was at this time that he brought home railway literature in a briefcase from which he gained a love for this obscure branch of railway activity. It was at this time that we travelled on the Balerno branch and saw both the LMS streamlined Pacifics and Cock o' the North before its destruction (although this may have been on a trip, following the birth of my sister, to Dundee in 1941). It is possible that Frank may have assisted George Dow in some of the research for The Story of the West Highland possibly in checking contemporary newspaper reports in Edinburgh.

Andrew Dow in Perception and statistics: meeting the LNER's public relations success (J. Rly Canal Hist. Soc., 2005, 35, 175-7) mentions that Dow's total staff numbered eleven in 1944: four in London, two in Manchester, two at York and three in Edinburgh. KPJ knows for certain that Frank was one of the two in Manchester; one of the four (or possibly more by then in London), and may have been one of those in Edinburgh where he presumably assisted with the brief histories of the NBR and West Highland lines. He received signed copies of most of Dow's LNER historical booklets..

Due to the complexities of life following the War (we were evicted from our temporary home upon the demob of its occupant) my mother, sister and self returned to London, but Dad did not follow until 1946 when he joined George Dow's office in 11 Blandford Square, where he was to remain until late 1948. During this period KPJ, his mother and sister took holidays in Stirling staying in Phil Jones's rented bungalow in Bannockburn and KPJ used to walk to the station to meet Dad off the train from Edinburgh. KPJ is reminded of this period as our eldest daughter now lives in Alloa and we travelled thence over the reinstated passenger service in September 2014. Kevin rememberss eating breakfast in the Golden Lion in Stirling in 1946 (and lunching there with Nationalist friends in 2014); arriving via Alloa and Dunfermline (High) in a thunderstorm (1946); and the Sentinel railcar.

During the period at Blandford Square he encountered Michael Bonavia (for whom he had a high regard). A few of the Diary entries give some feel for his activities: [22 July 1947]: This morning I went to King's Cross with a Film Unit making a documentary film. The subject was the motion of a locomotive at work and a Pacific "Felstead" No. 89 was selected for the "shooting". The light was not satisfactory, but three "shots" were taken and one may prove satisfactory. He was also very friendly with Roy Vincent, the photographer.(see Steam Wld, 2005 (222), page 38 for portrait of him: at that time he was Traffic Costing Officer to the Traffic Manager at Liverpool Street)

Friday 11.4.47

Notaable today for the lunch whih was given to the LNER Press Representatives

at the Liverpool Street Station Hotel. The occasion was a Meeting, probably

the last under LNER organisation, and Vincent my colleague & myself had

been invited to the lunch preceded by Sherry or Gin & Lime etc. I chose

the Gin and Lime and was a little surprised at its potency. The Lunch consisterd

of Hors d'oeuvre which I had, or Soup, Chicken with Cauliflower and Roast

Potatoes with which was served White or Red Burgundy (I like White Wine with

fish or chicken – a luxury seldom experienced), Bomb Glacée,

Coffee, and Cognac or Creme de Menthe. I had Brandy and althouigh far from

being an expert on any liqueur this Brandy to me mind had an unusual flavour.

I had a second helping to confirm my original opinion which was not

altered. A few remarks from Mr Dow, the Press Relations Officer and the two

Asssistant General Managers Mr Corble and Mr Bonavia brought the lunch to

a close, and I returned to the office where the barrage of 'phone calls

whicj I had had to deal with in the morning muultiplied in the afternoon.

I think that I more than earned my lunch or for that matter the small salary

paid to me today of all days. The variety of questions was considerable and

ojne might be forgiven for thinking that a great deal of intelligernce must

have been expended to think out some of the stupid questions put to me.

Home again and this evening Mary unfortunately has a high

temperature...

In August 1947 we had a family holiday in Dundee where he noted that we were invited onto the footplate of a [Y9] in Dundee Docks and Dad talked to driver about mutual acquaintances (he had worked in Dundee from 1917 to about 1935 and had collected medals for his First Aid and golfing activities.

Wednesday 18.6.47

Met Mr Vincent at lunch time at Kings Cross, and mert his wife and baby

a dear little girl with a winning smile perhaps a year old..

1947: Lots of telephone inquiries which he found hard due to deafness.

5.6.47. Farewell cocktail party for Sir Charles Newton CGM at which FLJ consumed too much liquor.

Diary entry: Tuesday 27. 4. 48

Today during a trial run over the Western Region..."Mallard" holder of the

World's record for steam traction of 125 miles per hour in 1938 and in actual

fact achieving 126 m.p.h. on its record breaking run at that time today developed

a mechanical defect at Savernake on its run from Plymouth to Paddington &;

was withdrawn — a GW locomotive hauling the train for the remainder

of the distance arriving 41 minutes late. I am sorry about this for the Gresley

Pacifics are wonderful steam locomotives but were subjected to heavy wear

and tear during the War years.

Diary entry: Tuesday 4. 5. 48

This afternoon Mr Dow wished me to go to the Gaumont British Film House in

Wardour Street to see a set of Pinschewer Films (pronounced Pinshaver Films

for obvious reasons as the English pronunciation could lead itself to caricature

of an unkind nature

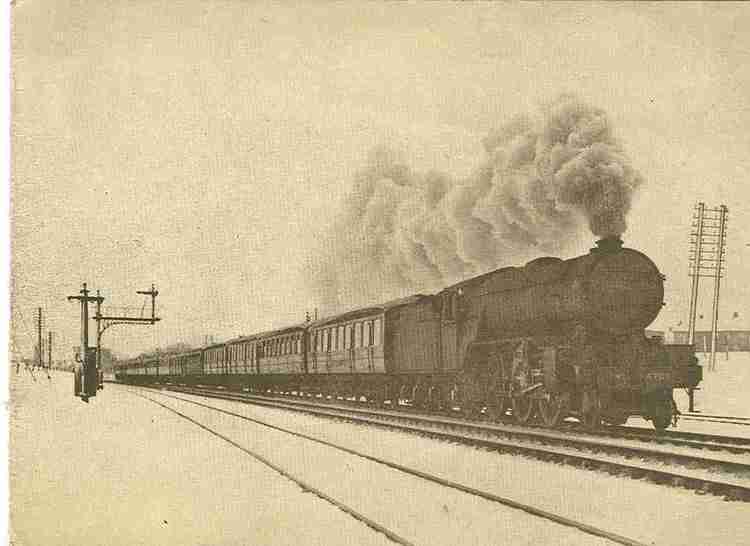

|

|

In late 1948 he became the Eastern Region's Public Relations Representative in Manchester with an Office (see 1953 letter for official designation, etc) in the old Great Central side of London Road Station. As houses were in short supply at that time we did a complex swap of houses with T.A. Germaine who had been the former incumbent in the Manchester office and was promoted back to London as PPRD. He moved to our former home in Bexleyheath, which had been purchased in the late 1930s, and we rented Ladbrook in Ladcastle Road, Uppermill, just below Saddleworth Golf Course and next to a disused stone quarry. It was approximately 750 feet above sea level. Frank's typist was Margaret Biggs, a farmer's daughter from Derbyshire..

This move provided first class travel for the family and enabled me to briefly savour the Manchester trams before their final demise. Although the vehicles were far less old than many of the ex-LCC cars running in London, their state was quite unbelievable as they appeared to have had no maintenance for at least twenty years. Similar comments could be made about the state of the railway infrastructure where dilapidated was far too spruce a term to be used. This was especially true of the LMS where nothing appeared to have ever been painted or cleaned: the LNER was markedly more caring. Crossing the road from Oldham Clegg Street, maintained by the LNER to Oldham Central, built by the L.&Y.R. at some distant time was like crossing the Styx. Clegg Street had a passimeter booking office and a colour light signal. Central was rotten through and through: this is not just superficial observation as was shown by the tragedy at Bury Knowsley Street when a footbridge collapsed under the weight of a football crowd.

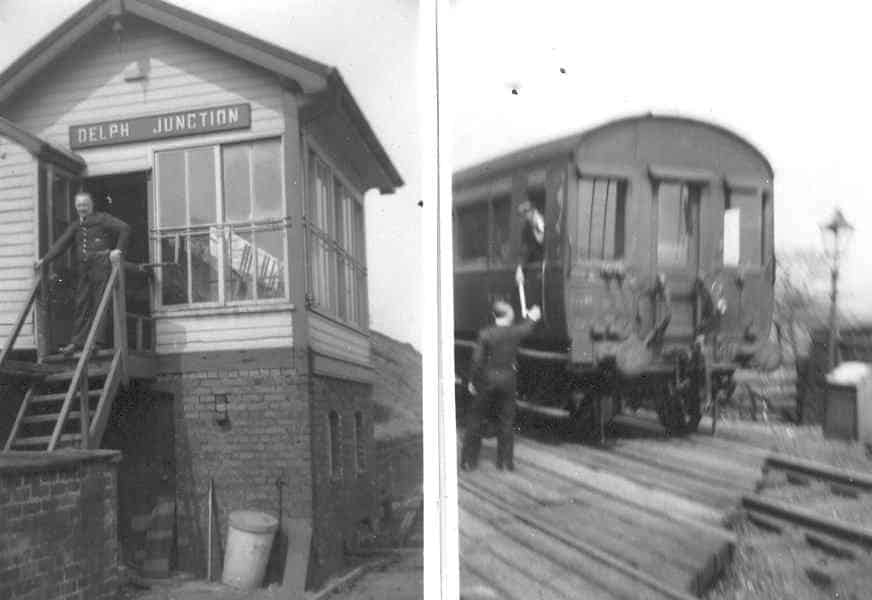

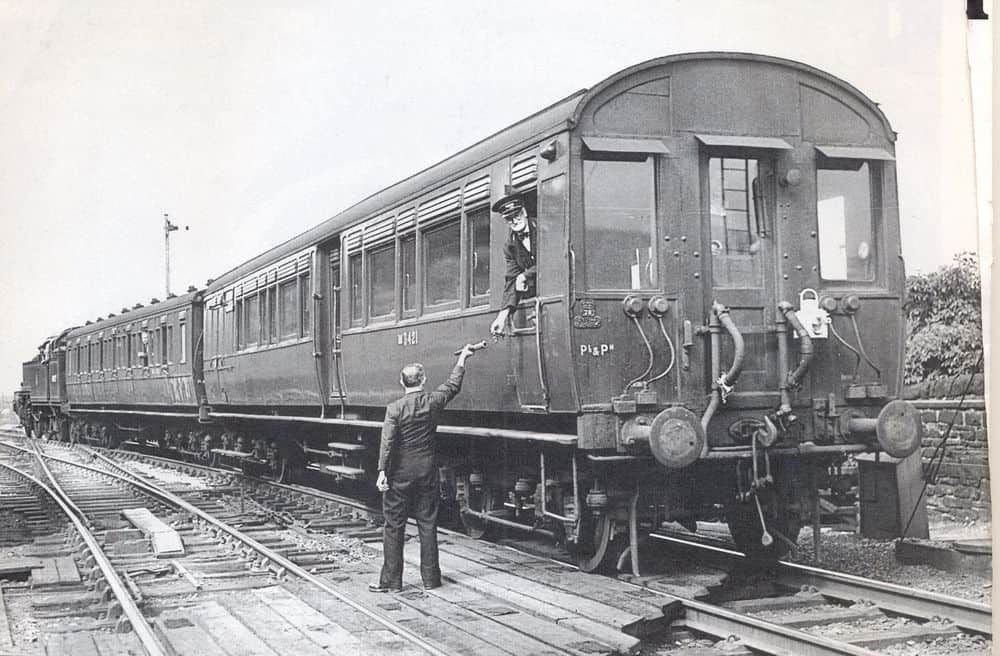

One of the delights of our new location was the proximity of Moorgate Halt and Delph Junction signal box occupied half the time by the friendly Mr Bill Hobson who allowed me to pull-off the signals, especially the motorized distant. It was a typical LNWR box with pull down locks on the levers. One view shows Bill at the top of the stairs and another receiving the staff from the driver of the Delph Donkey. Diary entry for Monday 30 January 1950: FLJ had intended to catch the 07.53 from Delph at Moorgate Halt to connect with the 08.07 from Greenfield to Manchester but due to frozen points the Delph Donkey was stuck on the branch, so Bill Hobson stopped the 08.07 at Moorgate Halt where my father and three others boarded the train to the amazement of the regular passengers from Huddersfield. FLJ was due to meet press at Gorton to inspect what he called an 0-4-4-0 electric locomotive. Unfortunately FLJ elected to travel to Gorton by electric traction (trolleybus) and this experienced traction problems of the snow and he got to Gorton after the press party. Theb photographs show Bill in his cabin, collecting the staff off the driver and (right hand) from the guard.

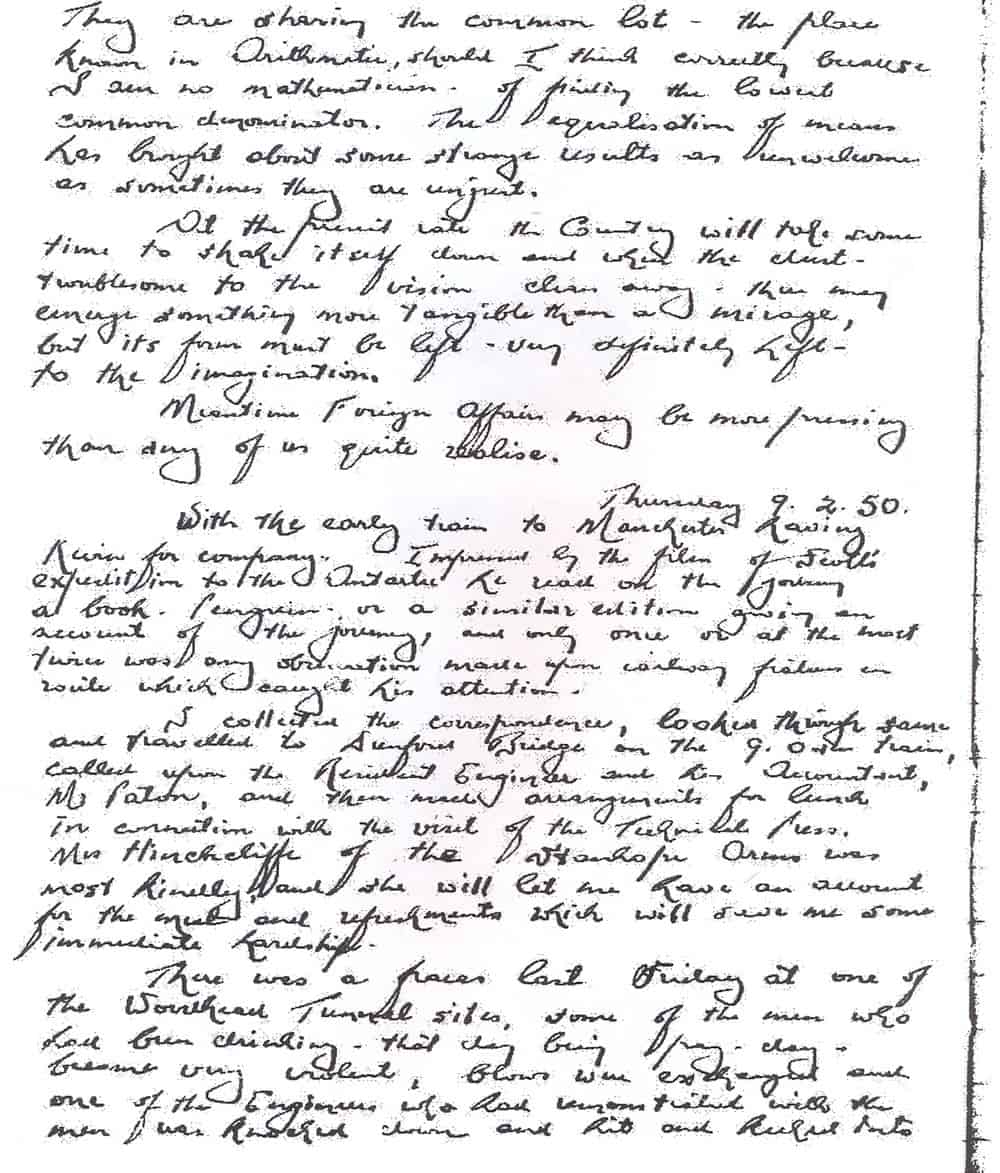

Thursday 9 February 1950.

With the early traim [approx. 07.30] to Manchester having Kevin for company.

Impressed by the film of Scott's expedition to the Antarctic he read on the

journey a book - Penguin - or a similar edition giving an account of the

journey, and only once or at the most twice was any observation made upon

railway features on route which caught his attention.

I collected the correspondence, looked through same, and travelled to Dunford

Bridge on the 9.0 am train, called upon the Resident Engineer and his Assistant,

Mr. Paton, and then made arrangements for lunch in connection with the visit

of the Technical Press.

Mrs. Hinchcliffe of the Stanhope Arms was most kindly, and she will let me

have an account ffor the meal and refreshments which will save some immediate

hardship.

There was a fracas lst Friday at on of the Woodhead Tunnel sites, some of

the men who had been drinking - that day being pay day - became very violent,

blows were exchanged and one of the Engineers who had remonstrated with the

men was knockd down and hit and kicked [see original diary entry at foot

of this page].

|

|

When making a final retirement move my father instructed me to look out for some papers which he had retained and these form the basis for this potential series of articles. The papers were official press releases, some faded photographs, a few booklets, a few letters, cards etc, some press cuttings, and an extremely useful paper by George Dow. This last forms the basis for the introduction as it is vastly superior to anything contained in histories of the LNER or of the early days of British Railways.

The paper entitled Railway public relations was presented by George Dow to the North Staffordshire Group of the Institute of Transport on 12th November 1954. It gives a concise history of this somewhat neglected topic and shows the complex task of reconciling the several systems inherited by the Railway Executive, its Regions, and the British Transport Commission. In the nineteenth century most of the functions now embraced in public relations work were performed by the general manager, although paid-for advertising was often placed by the secretary or one of the commercial officers. It was not until the early 1900s that the Great Central Railway established the first railway department to deal with matters which today are almost universally regarded as falling within the scope of public relations and publicity. The general manager of the line, Sam (later Sir Sam) Fay, created a publicity department as an integral part of his own office: its main function was to promote travel, with the aid of press and poster advertising, and booklets, etc. The department also dealt with press editorial matters, and it was fairly lavish with its "handouts" including numerous free passes, to encourage the press to write-up various aspects of what was then a growing system.

All the leading British railways possessed publicity or advertising departments at the Grouping in 1923, but subsequent developments did not follow in parallel. On the grouped railways the titles of the departmental officers all differed, and the organizations varied considerably by the last years before nationalization. On the L.M.S. the Advertising & Publicity Officer reported to a Vice-President and to the Chief Commercial Manager, and although it was the largest system, he had. no district organization of his own and no commercial advertising responsibilities whatsoever, this latter work being performed by outside contractors under the aegis of the Chief Commercial Manager. On the LNER the main functions of public relations were divided and the Press Relations Officer and the Advertising Manager, both possessing district organizations, reported to the Chief Genera1 Manager. On the Southern the Public Relations & Advertising Officer reported directly to the General Manager, as did the Great Western s Chief Officer for Public Relations, but the first named, unlike his colleagues, was also responsible for all public signs at stations.

One of the many tasks of unification which confronted the Railway Executive when the railways were nationalised was, therefore, that of evolving a public relation. and publicity organisation possessing, broadly speaking, common functions both at the Executive itself and in the six Regions of British Railways which had come into being. At the same time the new organisation had to be related to that functioning at the headquarters of the British Transport Commission. At the Commission the organisation was headed by a Chief Public Relation & Publicity Officer, assisted by a Public Relations Officer, a Publicity Officer and, in addition, a Commercial Advertisement Officer who was responsible for the selling of advertising space throughout the railways (as well as other parts of the nationalized undertaking), the. Regions performing the servicing and maintenance (such as bill-posting and provision of display equipment). as indicated earlier, the former L.M.S. system afforded a notable exception, for here the whole of commercial advertising, the selling of space, the servicing and the maintenance, was performed by contractors whose agreements did not expire until the end of 1953.

The Railway Executive accordingly appointed officers for public relations and publicity, whose work was co-ordinated by the Chief Officer (Administration), who was in turn responsible to the Chairman. In the Region the two functions were co-ordinated by the Public Relation & Publicity Officer, the division between his two assistants being identical with that applied at the Railway Executive, and this Officer was responsible to the Chief Regional Officer for the day-to-day work and, for functional matters, to the Railway Executive. The new arrangements came into being on 5th April 1949 but, with the disappearance of the Railway Executive at the end of September 1953 the latter's organisation was duly merged with that of the Commission and the Regional Public Relations and Publicity Officers became responsible solely to the Chief Regional Managers.

At this point in his presentation George Dow turned towards the specific structure of the London Midland Region, but as indicated earlier my father had been employed initially as the representative of the Eastern Region in Manchester. This was eventually to be the cause of problems and the eventual move of my father to the Scottish Region in Glasgow. Before leaving Dow, however, it is worth noting what he regarded to be the key elements of the job as managed within the London Midland Region, and making some notes on these criteria, as perceived from personal experience in a very different industry.

Dow defined public relations as relations with the press (that is newspapers and other journals),the news agencies (such as the Press Association and Reuters), the BBC (this has grown greatly since then), authors, free lance journalists and film (including newsreel) companies, both as regards dissemination of news and information and arrangement of facilities. Obviously, newsreel has since ended, but was significant then: the arrangement of facilities for filming remains an object of great interest to railway enthusiasts and there is a growing literature on some of the delightful absurdities of railways as portrayed on the "silver screen". These "faults" are solely due to the activities of the film companies and not to the provision of the facilities, although many writers have noted how the railway companies were unwilling to participate in the portrayal of head-on crashes and similar cinematographic whims.

Co-ordination of arrangements for public ceremonial (e.g. opening of installations) may seem a trifle arch nearly fifty years later, but it does convey a vital ingredient of the work and one which impinges upon railway enthusiasm. BackTrack included an evocative illustration of the naming of a Gresley V2 as XXX XXXX. Locomotive naming ceremonies were a typical part of such ceremonial, especially if a royal or military figure was involved in the ceremony, and it is a matter of personal regret that the author failed to record much of this material in his own sole bibliographical effort. Such ceremonies were especially important in the case of buildings and other major works as plaques might be left for future generations to be able to identify key events.

The next of Dow's criteria, dealing with public complaints in the press and applications from the public for railway information (other than of a commercial service character), photographs and drawings, will be well known to many enthusiasts, and some will have participated in the first-named sport, although the responses from our balkanized railways now seem quaint as compared with the concerted effort of an industry. One recent effort which made the contrast seem so great related to either the accidental division of trains in service or to the failure of automatic doors. In this the Train Operating Company publically sought to defend itself by transferring the blame to the rolling stock leasing company. One wonders what the great railway managers of the past would have made of this priggish behaviour which would have been more appropriate for the purveyor of faulty knickers. The quality of information has also declined and the enthusiast now has to rely upon unofficial sources, or museums.

Other activities recorded by Dow included: arrangements for public talks and co-ordination, where necessary, of public visits; distribution and exhibition of films, film strips and lantern slides (the production of which had been taken over by the B.T.C. Films Division); and production and distribution of the staff magazine (in the case of my father's activities this specific item did not impinge upon him until his arrival in Glasgow, where Norman MacKillop was to be an interesting colleague).

In the main my father was to be less concerned with publicity, although in Manchester he was in-charge of some of the bill-posting. Dow identified the following specific tasks: preparation and placing of press advertising; design, production and distribution of posters, train departure sheets, handbills and literature, and distribution of timetables; design, production and. distribution of window displays, and of display stands and enquiry offices at shows, exhibitions; siting, design and provision of public signs, indicators and. advertising disp1ay equipment and regulation of siting of automatic machines at stations, and responsibility for appearance of stations and property so far as these matters are concerned; and decoration of stations and property for special events.

Dow noted that "It will be observed, that the Railway Executive had wisely assigned to one department responsibility for the appearance of stations and property as regards signs, indicators, advertising display and siting of automatic machines, a step which only the Southern had had the courage to take some years before nationalisation. In anticipation of the change the Railway Executive had already standardised upon Gill Sans type for general publicity and for signs (in this it followed L.N.E.R. practice), had evolved a brief and simple basic code for signs (including regional colours) and had devised a trade mark or symbol in the form of a totem (not to be confused with the B.T.C. lion on wheel emblem)." It should be noted that the public image of the railway in those years running towards the "end of steam" which seems to hold a peculiar fascination for many railwayacs (using a useful anachronism) was a consequence of George Dow's policy for signage.

Until 1949 my father's occupation had had little affect upon domestic life. We travelled free, or at very little cost, but we always had. My father brought home a briefcase which might contain interesting literature, such as The Railway Gazette and Modern Transport, but work was work and home was home. Like many we lacked a telephone at home and television was far away in the future: listening to concerts and plays on the radio was the main domestic pastime. With the new position, we acquired a house with a telephone, and it soon became clear that this useful instrument could be highly intrusive, although we could only hear one half of the conversations. Every time that there was some minor accident the ‘phone would ring and in many cases it was obvious that the press were seeking to apportion blame in which case my father would have to reply that he was unable to state whether the signal had been at red, or that the driver had driven at excessive speed. In some cases these exchanges would extend over a considerable period, and it has tended to colour my views on the impartiality and lack of responsibility of the national press.

Sometimes our bungalow, high in the Pennines, would be informed of major events long before they became news. Thus we were to be privy to the distress of the Princess Victoria before it sank although its sphere of operation was well outside my father's remit. Sometimes, local events were sufficiently severe for the main press response to moved further up the chain of command, and in these cases statements tended to be made through the press agencies. The Irk Valley accident in which one of the Bury electric trains was displaced off a viaduct by the impact of a steam locomotive which had failed to stop was an episode in this category.

The following story based om wagon repair at Doncaster has a remarkable sense of what the railways were like in the 1890s not of the 1950s and the Festival of Britain.

|

It will be obvious to most readers that the railways in the early 1950s were very different from today, but it may be less evident that the media were also very different. Television had yet to reach the North of England. People went to the cinema regularly, and newsreels were watched with interest. In the case of villages, like Uppermill where we lived, the newsreels might be out-of-date, but they, like the old films, were enjoyed as nothing else was available without a lot of effort. The radio was a major source of news and entertainment and much was produced nationally. There were far more newspapers, especially evening ones, and many titles have disappeared, notably the Daily Herald, or have changed in character. Manchester was a major regional news centre and produced Northern editions of many national dailies. At that time the Manchester Guardian was just that: a major regional newspaper.

|

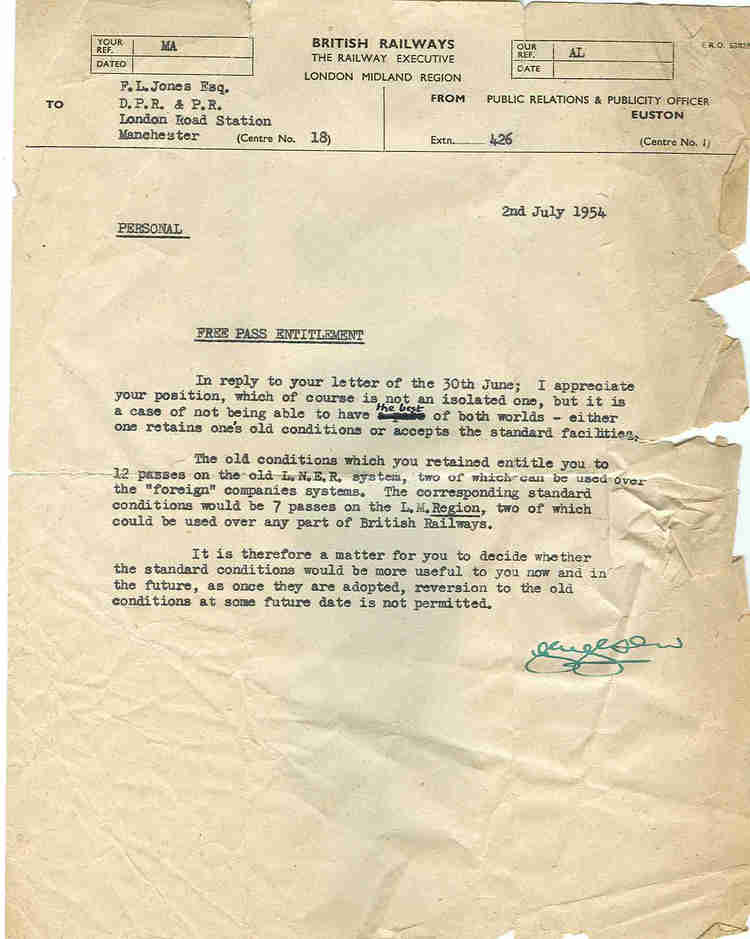

My father's "territory" tended to change with time, but on appointment extended across to Doncaster, and perhaps even to the Lincolnshire Coast, down the Great Central to Leicester and across the CLC to Liverpool and Southport. Until extremely late in his career he retained his LNER conditions of service which gave twelve free passes per annum as against seven for others in his position (see Dow sitting in the Chair of Solomon above). These journeys had to be made on LNER routes: thus the 10 a.m from Marylebone (first stop Harrow-on-the-Hill) became our normal means of travel from London, although for some obscure reason we had been allowed to use The Comet from Euston on our first journey north. The locomotive hauling the train, a Royal Scot, was painted black and this served as a suitable prelude to all that was bad about things L.M.S. as distinct from the more colourful LNER or Southern where important trains were hauled by coloured, streamlined engines. Although this initial journey would be in a first-class compartment, I was shocked to find that the kitchen car was gas lit, and exuded gas fumes. For some reason, and David Jenkinson may hate this, the double doors to the compartment seemed less convenient than the single doors to which I was used.

The office was a small one and the only other member of the office staff was a clerk/typist, a Ms Biggs who came from a farm in Derbyshire. There was a typewriter, and presumably two telephones, one for the railway network and one through the Post Office to communicate with the press, or to state that "he would be working late". There was an excellent view down the ramp to the trams and the general squalour of central Manchester. There was a small amount of pre-War publicity material which would have enhanced my personal library, but pleas for its removal fell on my father's deaf ear.

The "big event" of my father's period in Manchester was the construction of the new Woodhead Tunnel and the related electrification of the former routes between Manchester and Wath-on-Dearne and Sheffield. It is difficult to believe that so very little of this vast engineering project survives in service, although to someone like myself who had always questioned the long-term viability of coal-burning it should not be so surprising. Many of the metaphors used to describe the route, such as a coal conveyor, stressed the pre-eminent requirement, namely the need to carry coal across the Pennines; once this need had passed there was no need for the modernized railway. It is considered that the best way of illustrating my father's involvement in this doomed project is to reproduce some of the press releases which he issued with some of the response which these engendered in the newspapers published at the time.

Extracts from Frank's diaries made at time of Mary's death im 2005

13 December 1949: To Guide Bridge to interview ticket collector due to retire after 50 years service. He remembered the 11.15 pm train from London Road to Stalybridge as "Theatre Train". It was usually packed to capacity and was met by horse drawn cabs looking for fares

14 December 1949: 1 pm met director of Film Unit, Mr Oliver, and went off to Guide Bridge

15 December 1949: travelled to Barnsley Court House to visit Wath Marshalling Yard.

8 October 1951: Visited Manchester Guardian and talked with Industrial Correspondent of Evening Chronicle.

9 October 1951: To Hyde Central to meet signal woman a nd

Ashton Reporter reporter and photographer.

Re ceived application form for District Public Relations & Publicity

Representative Manchester (to add poster publicity and outdoor coommercial

advertising)

16 October 1951: Spoke to Men's Meeting of Dinting Parish Church on Manchester-Sheffield-Wath electrification.

25 October 1951: To Sheffield to see Frank Ward, a collegue on the PR side.

26 October 1951: Travelled up to Euston on Mancunian

with Norman Mottenhead for interview for post.

Richard Dimblebey on train in dining car.

15 November 1951: Phone call from George Dow to say had been appointed District Public Relations & Publicity Representative for London Midland Region, Manchester. Not to tell anyone until Flowerdew, District Passenger Superintendent had been informed.

16 November 1951: Visit from Mr. Price of York Office. Returned wishes for McDonald, former Edinburgh collegue.

20 November 1951: Meeting with George Dow and B. Thomas, PR & PO Eastern Region and Germaine, his assistant.

23 November 1951: Meeting with R.C. Flowerdew at Hunt's Bank

26 November 1951: Electric locomotive at Oxspring Junction Signal Box acting as electric banker photo session.

30 November 1951: Ma critically ill.

Frank with wet fawn raincoat is looking to right towards press photographer at Woodhead Tunnel breakthrough:

|

Clearly one of the highlights of this activity was the breakthrough in the new tunnel. The text from the official press release is reproduced below.

WOODHEAD NEW TUNNEL

COMPLETION OF PILOT TUNNEL

A further definite step towards completion of the new double line three-mile long railway tunnel between Woodhead and Dunford, on the Manchester - Sheffield main line, will be the joining up on 16th May 1951 of the pilot tunnel which has been driven, during the last two years, through the rock and shale of the Pennine hill country.

A simple ceremony will be staged to mark the occasion, when Mr. J.C.L. Train, M.C., M.I.C.E.., Member of the Railway Executive responsible for Civil Engineering, will fire the shot to complete the break-through. The charge will be detonated from the bottom of No.2 Shaft, in the presence of a small group of engineers which will include Mr. J.I. Campbell, Civil Engineer, Eastern Region, under whose direction the general scheme for the tunnel was prepared; Sir William Halcrow, head of the firm of consultants who are supervising the construction; and Sir Andrew MacTaggart, Director of Messrs. Balfour Beatty and Company Limited, the contractors.

Representatives of the workmen employed on the tunnel will also be present. The point of break-through will be about one mile from the Woodhead end of the tunnel.

Completion of tho pilot tunnel, which is about one fifth of the sectional area of the final tunnel, will be followed by excavating to the full size of 31 ft. in breadth and 24 ft. in height, throughout the total length. Lined with concrete and twin tracks laid, the new tunnel is expected to be completed towards the end of next year.

The effort was fully rewarded by an extensive article, "Woodhead pilot tunnel sections linked" in the Manchester Guardian on the following day. Befitting the gravitas of this paper all the key figures are featured in the account. Note is taken of Mr J.C.L. Train of the Railway Executive who pressed the switch which fired the shot in the presence of Mr J.L. Campbell, civil engineer of the Eastern section [sic The Grauniad has been at it for a long time] of British Railways, Sir William Halcrow and Mr Peter A. Scott, principals of the consulting engineers, and Sir Andrew MacTaggart, director of Balfour, Beatty and Co. Ltd., the contractors for the work. This section reads like a court circular and certainly confirms the importance of what Dow termed "ceremonial".

The Daily Dispatch in a short piece entitled "Tunnel men work to -inch" presented the human interest side of the story and may have relied upon interviews, or material made available by the contractors. The men actually involved at the rock face in the breakthrough were featured, namely 50-year-old Walter ("Wattie") MacColl and 43-year-old Harry Fowler. The "Foreman in charge of the job is a Scot: "Sandy" Wivell of Methil, Fife, but most of the workmen are Poles. They earn about £11 for a 72-hour week, plus a 2s. Bonus a week for every foot more than 75ft." "Walter, meet Harry!" was the Daily Herald's headline. In this description the breakthrough was only 400ft underground as against 500ft in the Dispatch. The statement made by Sir Andrew McTaggart, who represented the contractors, who claimed that when the tunnel is completed "one of the worst transport bottlenecks in Britain... will have been abolished" has an especially poignant quality in the light of subsequent events and the continuing problem of the state of the road infrastructure between Manchester and Sheffield.

Obviously, it was necessary to maintain press interest in the project, and visits were arranged for groups of journalists. Such a visit produced a short feature entitled "Cold job under the hills" in the Yorkshire Post on the 2nd December, 1950. This was written when approximately two thirds of the pilot tunnels had been completed. The reporter had obviously met Mr J.D. Dempster, the Resident Engineer. Although the journalist had been impressed by the mud, cold, damp, gloom, noise, the million tons of soil and rock, and the cost of £2,800,000, the human interest aspects predominated: "Why did they come to work in the bowels of the lonely moors...Money. That is the answer for five out of six men. Some of them in a week can earn nearly £20". Clearly, it is essential to adjust oneself to the finances of the 1950s: the Woodhead Tunnel would have been a minor Millennium Project!

Sometimes, it is not possible to find a direct correlation between a particular press release and the remaining press cuttings. This is the case with a press statement concerning wiring trains.

|

|

|

MANCHESTER-SHEFFIELD -WATH ELECTRIFICATION SCHEME

A WIRING TRAIN" AT WORK

Introduction:

The Manchester - Sheffield - Wath electrification scheme approved by the Directors of the former L.N.E.R. in 1936 had made some progress when the outbreak of War in 1939 necessitated suspension of work. In the late summer of 1947 the Minister of Transport gave approval for work to be resumed.

The scheme is being carried out in several stages:— 1 — Wath Marshalling Yards, near Barnsley, to Dunford Bridge. 2 — Dunford to Manchester (London Road), and 3 — Sheffield to Barnsley Junction, near Penistone Station.

Tracks are being equipped on the overhead line system at 1500 volts direct current, similar to the equipment used on the Manchester — Altrincham, and Liverpool Street — Shenfield electrifications.

The return current to the sub-stations is taken through the track rails and each rail joint is provided with a stranded copper bond welded to the rail heads.

The above extract was dated 4th November 1950, but a story entitled "Tug-o'-war on Dinting Viaduct" appeared in the Glossop Chronicle and Advertiser on the 17th August in the following year. Reporters, even from such desolate locations as Glossop, appear to be ill-prepared for the elements: "Cold, damp air blew on our faces on Sunday morning as we stood on Dinting Viaduct and watched 22 men play tug-o'-war." The men were heaving a pilot cable into position on behalf of W.T. Henley Telegraph Works - control cable for switchgear operated from Penistone control station.

Drivers change from steam in 3 lessons. Sheffield Telegraph, 1951-07-10.

Human interest story

Wath-on-Dearne

one week theory

one week on locomotives on four mile Wath-Wombwell stretch

Back to steam: then eventually work up to Penistone

"new drivers unrestricted by any age bar"

Six drivers sent to Liverpool Street-Shenton [sic] electric line to

qualify as "leading motormen".

"Three main advantages, they all agree, are cleanliness, comfort of

operation and protection from the weather"

ELECTRIC LOCOMOTIVE FOR FESTIVAL OF BRITAIN

British Railways Gorton built electric locomotive No. 26020, is to be exhibited at the Festival of Britain Exhibition in London. This class of locomotive is one of a number designed and built for use on the Manchester! — Sheffield — Wath electrification scheme, and is capable of dealing with all classes of traffic on the route whether express or local passenger services, fast freight, heavy mineral or goods trains,

The mechanical parts for the locomotives, consisting of the bogies and bodies, are built and assembled at Gorton Locomotive Works, and at Dukinfield Factory the electric motors and other electrical equipment are installed by Metropolitan Vickers Electrical Company Limited0

This engine will form one of a trinity of motive power employed by British Railways representing steam, electric and diesel-electric traction, and all three are to be on exhibition ut the South end of Charing Cross Railway Bridge.

Access will be from within the grounds of the South Bank Exhibition.

One of the least promising documents to be found is a "Filing Index" which had been started on the 1st March, 1949. The index is in a quite extraordinary order, yet parts of it, especially that relating traffic, demonstrate some of the priorities of the time. The first heading is "stories", that is press releases, and this was subdivided into those issued by the Railway Executive; by the London Office (Eastern Region Headquarters); the York Office; and by the Manchester Office. A Weekly Report was demanded. There were files for all the usual office routines (stationery, sickness, accounts, etc), but one file was given over to: Letters of Complaint and Bad Publicity. There were files for Train Services, and sections within these for train service alterations, new timetables, and for High Speed and Named trains. The notion of high speed trains in 1949 must have been a carry-over from the pre-war Coronation era. Were the many complaints about journeys on The Master Cutler and The South Yorkshireman filed with the sub-files for the specific trains or with the letters of complaint?

Following a sub-file for Seat Reservation, there was an extraordinary melange: Cartage (horses, lorries, etc); BBC; films; photographs; exhibitions; lectures; Press and Public visits to Railway property; and individual files for goods depots; marshalling yards; and locomotive sheds and staff. At this point which is less than one third of the way through this list, it is worth noting that the arrangement appeared to break every single convention for establishing a filing system and clearly it would be tedious for the reader to enumerate all the reamining headings and a few further examples will suffice. There was a file for Mishaps, which included instructions regarding press facilities at accidents. Contemporary events were reflected such as the interchange of locomotives which had been conducted in part on the Great Central Section. The files relating to freight included out-of.-gauge loads, large and special consignments and thirty files later Freight Traffic with sub-files for glass traffic; the carriage of agricultural machinery; poultry traffic; beer traffic; conveyance of animals; fish traffic; pitch traffic; and sugar beet and potato traffic. The absence of coal, steel and chemicals is remarkable. The presence of pitch is equally extraordinary. There were files for the Best Kept Station Awards and several for what would now be termed safety at work. About half way through the list was a file for pilferage. The formerly coherent nature of the business is reflected in the files for hotels; docks; ferry services, and railway workshops.

Actual Diary extracts

17 10 52 Met George Dow at Adelphi Hotel in

Liverpool: not home until 8 pm.

19 10 52 [following Harrow disaster]: There is a great deal of open

discussion in the newspapers upon the subject of "Automatic Train Control",

a device which gives audible warning to the driver of a locomotive together

with a partial application of the brake should he pass a signal at danger.

Sir Felix Pole, a former distinguished officer of the former Great Western

Railway attacks in the "Sunday Express" today the attitude of the Railway

Executive [and the former main line companies] for their non-adoption or

opposition to the safety method adopted by the Great Western Railway since

1906. [FLJ then anticipated opposition from Treasury for lack of funds even

following Harrow disaster]

2 10 52

Comment on station indicators at London Road station: Eastern Region for

Platforms A. B and C and numbers for London Midland Region destinations.

Same meeting: interview with reporter from "Manchester Evening News" on vandalism

in trains

Part 2 (Scottish Region)

|

|

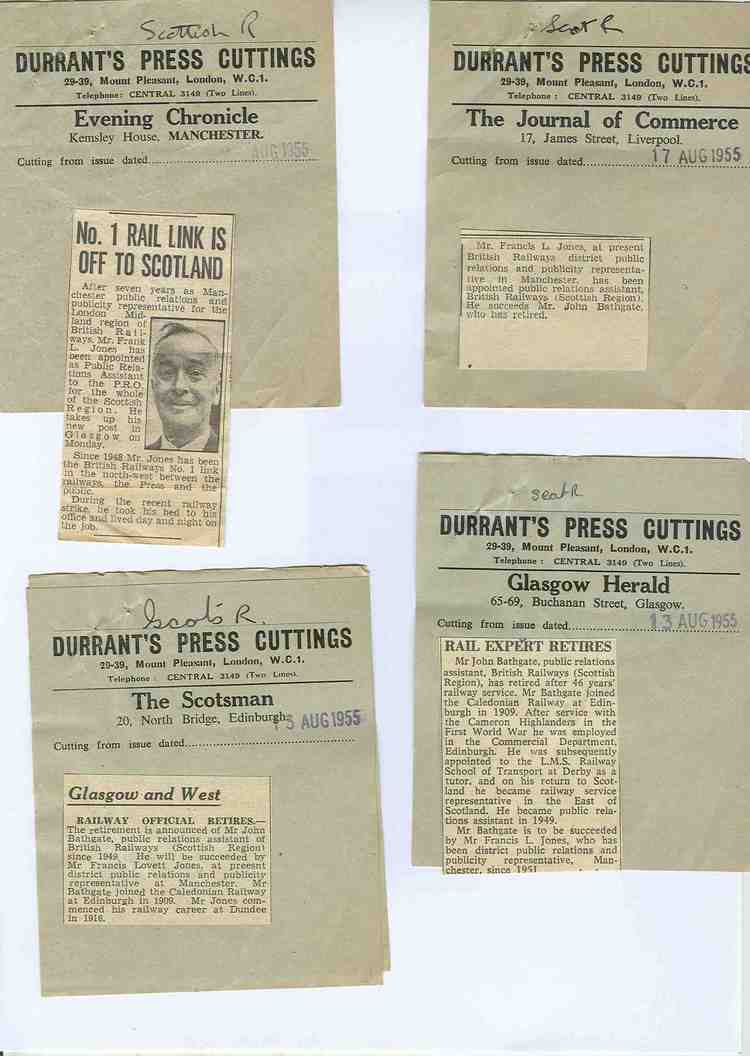

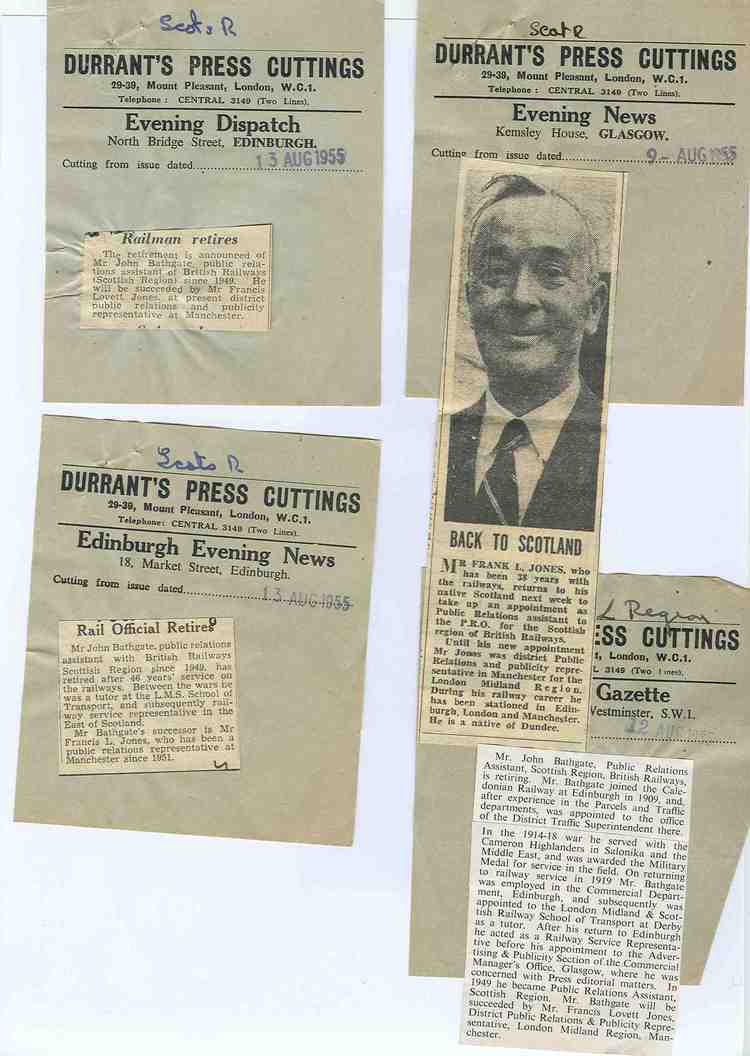

My father moved to become Public Relations Assistant, British Railways, Scottish Region (press cuttings above) in August 1955, in succession to John Bathgate who had retired. Bathgate had joined the Caledonian Railway in Edinburgh in 1909 and had enjoyed a varied career including service with the Cameron Highlanders during the First World War, when he was awarded the Military Medal; employment in the Commercial Department in Edinburgh; tutoring at the L.M.S. School of Transport in Derby prior to his appointment to the Advertising & Publicity Section in the Commercial Manger's Office in Glasgow. In 1949, as a consequence of nationalization, he acquired the position to which my father succeeded. My father reported to H.M. Hunter, who in turn was responsible to James Ness, the General Manager. Following Hunter's retirement in XXXX my father reported to a former journalist Colin Neil Mackay. At the end of this page there is an undated document which attempted to describe the Public Relations activities of the Scottish Region. It is undated, but followed the naming ceremony of Clan Buchanan and preceded the transfer of the Countess of Breadalbane from Loch Awe to the Clyde. Incidentally, Alexander J. Mullay's Scottish Region: a history, 1948-1973 is very disappointing in respect of PR activity..

|

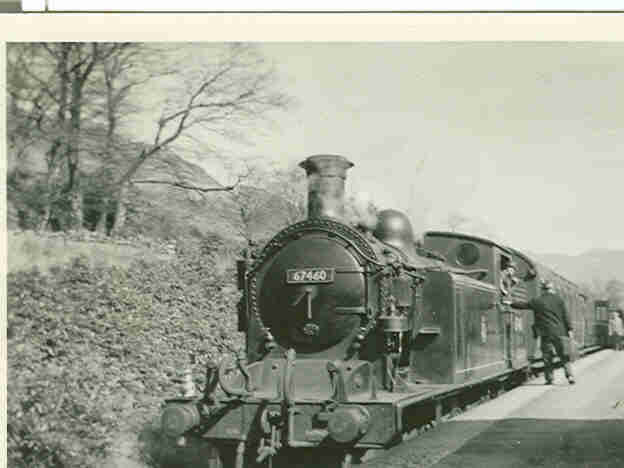

This move came as a great personal shock as I was performing National Service at the time in Cyprus and had expected to return to the North of England, instead of the strange city of Glasgow, made stranger by the first leave being spent in a time of thick November fog! During this period a trip was made to Arrochar & Tarbert on the push & pull: I suspect that we travelled first class as my parents enjoyed a Scottish Region all-line pass (first class travel on push & pull units was rare at that time). Once again, modernization of the railways was a major feature and this included the introduction, and subsequent problems, with the "Blue trains", although other facets also made an impact, notably the Inter City diesel multiple units between Edinburgh and Glasgow, and eventually the heavy impact of the Beeching Report and its closures. It did, however, enable me to explore much of the remaining Glasgow tramway network, including some of its inter-urban routes, and on the last Edinburgh trams, and to participate in that glorious folly of the preserved Scottish steam locomotives.

As in the case of Manchester, it is necessary to note the nature of the Scottish media which it that time enjoyed a considerable independence. The two "heavy" papers were The Scotsman and The Glasgow Herald, but both Aberdeen and Dundee enjoyed their own newspapers, and The Daily Record was the working class paper. Many national papers, such as The Express, produced Scottish editions in Glasgow. Glasgow had two evening papers and television had both become a national facility and had entered the domestic environment.

An article in Backtrack, 2013, 27, 235 by Alistair F. Nisbet on the Television Trains organized by the Glasgow Evening Citizen must have involved activity by Frank, although there is no mention of this in the article nor of the names of any Scottish Region staff other than the train crews. The trains came into service in September 1956, just prior to Kevin taking up residence in Glasgow following demob

The office was situated in the nether regions of St Enoch's Station in Glasgow's insalubrious Saltmarket. The buffet in the Station formed a suitable place for lunch and the location for several meetings with Norman McKillop, whom at that time was the Editor of the British Railways Magazine. The fascination of the buffet to this notable character was the ready availability of draught Bass, a commodity which at that time was noticeably absent from Scotland. The colour transparency taken by T.J. Edgington on 9 May 1959 (reproduced Backtrack, 2006, 20, 462) includes the building, and further down the platform (out of view) was the buffet.

It had been tempting to write a letter concerning John Macnab's interesting article on Glasgow's "Blue trains" especially as it clearly demonstrated the vast gulf between the formerly integrated railways and the ludicrous and dangerous system produced by the Tory scrap metal merchants. Macnab showed the versatility of the former system which enabled electric services to be replaced by steam in an incredibly short time, whereas the Hatfield disaster led to the replacement of most of the train service for a period extending to nearly two months, and nobody (especially anyone? responsible for public relations was able to state why).

It would have been helpful if Macnab had cited his sources and had discussed the nature of the faults which caused the protracted, temporary withdrawal of the blue trains. The extensive and rather florid quotation was taken from a brochure written by George Blake1. My initial reaction to the prose was that it belonged to my father, but such writing was normally proscribed. George Blake was a well-known writer about Scotland and a typical product of his was The Heart of Scotland published in 1934, but there were many others. The preparation of the brochure certainly involved my father, and he was particularly impressed by the working methods of the top free-lance photographer who took most of the photographs for it. He accompanied him on the photographic expeditions. Unfortunately, my father's reaction to George Blake escapes me, but I have no doubt that he would have wished to emulate such activity. He frequently expressed his appreciation for those who possessed "private means" which enabled them to write and travel: Hamilton Ellis was probably one such paradigm, George Blake may have been another. The brochure was an unusually lavish production and featured a cover by Cuneo (with an electric train passing steam tugs at Bowling and a steam-hauled freight). One of the interior shots with young ladies dressed in polka dot dresses with vast skirts brings back happy memories of courtship. It would now be difficult to be certain whether the flouncey dresses and the bulbous shape of the Blue trains made a common fashion statement.

The early suburban electrifications in both Glasgow and in London involved working at twin voltages: 6.25kV and 25kV: the lower voltage was used where headroom was restricted and switches between the two voltages had to be achieved whilst the trains glided through neutral sections. Eventually it was found the clearances for the higher voltage could be reduced and the 6.25kV sections were gradually eliminated, the last one being on the very constricted approach to Fenchurch Street. Initially, it had been intended that the approach to Euston would have to be at the lower voltage.

The failures were mainly in the transformers which led to serious explosions, in one of which a guard was seriously injured. The fault was mainly due to design of the transformers, inadequate venting, and to some extent failings in the mercury arc rectifiers and circuit breakers which caused the transformers to be highly stressed, especially during voltage changeovers, or through pantograph bounce. The most serious faults occurred in Glasgow, but the North East London electrics were not immune, but did not have to be withdrawn. To some extent the more advanced rolling stock (in electrical terms) for the LTS electrification saved the day.

In retrospect, it seems extraordinary that mercury arc rectifiers, of the sort which caused so much amazement in the television documentaries on the Royal Opera House at Covent Garden, were ever used in multiple unit electric trains, and it is fortunate that germanium and silicon rectifiers became available to enable the mercury arc devices to be replaced. I would agree that the units have worn well: I last travelled on one returning from viewing the "tall ships" in Greenock. They still run well, although the Gresley bogies impart a somewhat old-fashioned motion, but which was vastly better than that provided by the BR Mark 1 bogies. Mr Macnab is perhaps incorrect to imply a link with the Liverpool rolling stock: the Shenfield units were perhaps more similar, and there is some similarity with the Metropolitan line A60 stock, notably the generous width; this stock has enjoyed similar longevity. The forward view was marvellous whilst it lasted.

One of the items which has survived was a simple brochure produced to mark the introduction of diesel locomotive hauled three-hour express trains between Aberdeen and Edinburgh. The launch date was 4 April 1960. The service was launched with the departure of 07.30 from Aberdeen waved off by the Lord Provost who had breakfasted with James Ness in the Station Hotel. The General Manager of the Aberdeen Journals travelled on the train with the District Traffic Superintendent, breakfasted on the train , left the train at Dundee, and returned in time for lunch with Cameron of Locheil and James Ness. It almost sounds Victorian in its splendour: what does the local bus-train company offer when new-liveried stock arrives?

A copy of the Beeching Report Part 1 is marked with Frank's jottings in ink on the cover and pencil inside and on page 126 the total number of Scottish stations to be closed (435) is underlined thrice. Clearly Beeching was intended to be savage in its cuts. Sadly much of the publicity material related to closures: most follow a uniform patterrn, but a rare exception was Ernest Marples' statement concerninng his refusal to consent to the closure of the North of Scotland Lines. This was the subject for a press release on 16 April 1964 where Mr William G. Thorpe added some pointed remarks to the statement which included: "If only half of the people who have sent in protests about the proposed closures will regularly and frequently use the railway the prospects of the future can look much brighter".

One of the obscure, but delightful, episodes which happened on the Scottish Region was the restoration and running of several preserved pre-grouping locomotives. There was an extensive correspondence between my father and Mr Hogg the archivist in Edinburgh concerning this locomotive which led to a slender brochure printed by McCorquodale to mark a run on 18 March 1958 from Perth to Edinburgh. The cover is reproduced below:

|

Frank on right (had not realized that walking poles had been invented then): who he was with, and why he was there will remain a mystery until his Diaries are examined |

Presumably with James Ness, GM Scottish Region, either on way to Caledonian Princess junketing or for launch of Inter-City DMUs |

Inauguration of Stranraer Larne service with Caledonian Princess (Frank far right) |

PUBLIC RELATIONS AND PUBLICITY.

The Public Relations and Publicity Department of Briish Railways bas become more widely known throughout Scotland during the past four or five years than similar Departments run by the former Railway Companies. One can say, however, that there has always been a Public Relations &: Publicity Department or Departments of some sort or another throughout the entire history of the Railways of this country although the name Public Relations & Publicity was probably never heard in these far off days.

Public Relations work in its modern form came into being in the United states of America. at the beginning of the present century although it is only in recant years that the name has become so widely known in this country, indeed it is only since the end at the war that the public have taken an interest in the matter at all. The function of public relations is a separate and distinct function a1though in our organisation public relations and publicity are under one supervision. This organisation is perfectly sound because although their functions are different, public relations depends on publicity for much of its material.

Since those early days, there has come into being in all the major industries not only in this country but in other countries of the world a department of the industry which covers public relations. Much nonsense has been written and spoken about public relations but the work of this department is simply to present the business done by the undertaking to the public in the best way and to convey to the management the reaction of the public. Boiled down, this simply means the maintenance of good relations and mutual understanding by service and co-operation.

Each of us possesses the power to influence other people and to cause other people to form opinions. How often have we ourselves when we go into a large shop or into a large railway station where we do not know our way about immediately formed an opinion of the organisation based on the helptul or negative attitude adopted by the emp1oyees from whom we ask advice.

While I have stated it is the f'unction of the Public Relations man to foster good relations and mutual understanding, he has sometimes a very difficult task in front of him and qu1te often at the beginning the task may seem insuperable. He may be bombarded from one end of the country to another, feelings may be aroused but provided he does not quite lose the place, he will in the end manage to convey to the public, and secure an appreciation, the reasons for the course of action adopted by his employers. We have recently come through – in fact are still passing through – difficult days in connection with the Clyde Pier controversy. From the point at view of British Railways, the difficulty is solely one of economics. It would be an easy matter to provide any services at any time if one had not to find the money to provide that service and this is what is happening on the Clyde today. We are losing roughly £150.000 per annum on these services and having regard to the terms of the Transport Act, it is essential. that these services should be made to pay their way. Nevertheless, progress has been made by consultations with thc various interests and it is confidently expected that this progress will be continued.

In the Scottish Region, the Public Relations staff of the Department provide an effective channel for the dissemination of regional news and information through the media of the Press, the B.B.C. and the Cine News-Reels including the circulation to the national and technical press o£ regional news items of major interest. In this connection, the Press and the B.B.C,. in Scotland are kept fully informed of developments on British Railways. In the Scottish Region, we are constantly in touch with, the Press throughout the twenty-four hours of the day– during the day by personal call and by telephone, during the night by telephone. We are advised by Railway Headquarters Control of every happening in Scotland and it may surprise many ot you to know that through a system of 1ocal correspondence the newspapers quite often have word of a mishap as soon as we do ourselves. so that it is necessary we are in a position to give them the true facts in order that no garbled accounts may appear in the newspapers next morning. The Press appreciate. the help given to them. They have no desire to print wrong information although I sometimes think they like to give it a twist to make it as newsy or sensational as possible.

It has always been the policy of British Railways to give the Press the true facts and. to hide nothing from them, in other words, in the unfortunate event of an accident taking place the Press are admitted to the scene of the accident to observe and take note of what is happening but natural1y they do not seek to interrupt the work of the railway staff at such a scene but rely on information being given to them for publication in their papers.

Apart altogether from instances such as that. we have many items of general public interest and the Press and the B.B.C. are always glad to know about them. This necessitates the preparation of what has become known as a handout although I personally do not like the term. These press issues require to be written in such a way as will appeal to the type of paper wh1ch is using the material. e.g. the requirements of a gossip paper. are different from that of the commercial paper and again there is a difference between the commercial paper and a technical journal. Each has to be treated. in a different way and the member of the staff engaged on this work must have a nose tor news.

We have this week introduced in Scotland the first of the "Clan" class locomotives. The press issue was written several times - once tor the Dailies, again. far the weekly papers and again for the technical journals. The event was also recorded by the B.B.C. and will be referred to in, I understand News of the Week.

So far as Cine News-Reels are concerned. the News-Reel Companies are most anxious to obtain information of major events and I have no doubt many of you have seen the news-reels which appeared during the time of the severe flooding in Scotland when so many of our bridges were washed away and our permanent way damaged so extensively. This was the greatest flood disaster which had ever taken place in this country and a permanent record of it has been made by British Railways Film Unit who have moulded together a film which will f'orm a permanent record of tho oocurrence and which will be of value to students in the years to come. It may be of interest to know that copies of' the film of the Scottish floods was sent to the United States of America,. to Canada, to European countries where we have Agents. and has been shown to several millions of people throughout the world.

The Cine people win again feature British Railways within the next week or so when the Countess of Breadalbane is moved from Loch Awe to the Clyde.

You may have noticed in the public press letters under the nom de plume of "Mother of Ten", "Disgusted" in regard to indignities or inconvenience which they allege they have suffered while patrons of the Railway, but many of these complaints are put down on paper in the heat of the moment and if' instead of putting them in the pillar box at night, the writers put them under their pillows before they went to bed, their letters would never have been despatched. In the light of the morning, what has previously seemed an item of magnitude quite often assumes its correct perspective. Nevertheless in some cases there is a grain of' truth in the writer's complaints; in other cases, the letters are perfectly correct - we have failed in our job in a particular instance. If we have failed, we admit it; if' we have not failed, we try to convince the writer that he or she has made a mistake. Having regard to the magnitude of the organisation which we serve, the number of passengers who travel by our services and the large volume of freight which we handle, the criticism levelled against us is infinitesimal.

Please do not think we object to criticism, after all criticism is merely an expression of opinion and expression of opinion can be most helpful to any organisation so long as they are honest expressions and do not have their origin in a contorted political outlook no matter what the politics of: the writer may be.

I have recently received a lette:r from a gentleman in a very responsible position in Northern Ireland who expressed himself in very strong terms about the lack of service which he had received from British Railways - stating they had taken no interest in his consignment at all and threatening that unless he received a satisfactory explanation and an apology for the trouble he had been occasioned, he would not send any more traffic by British Railways.. He followed this letter up the next day with another letter apologising himself for the tone of his letter and stating that British Railways were not to blame at all.

We have a very live Section dealing with the distribution and exhibition of' films and these films are ot many types – some deal with public relations activities, some publicise tbe work of the various Executives and some are staff training fi1ms. Where necessary we provide a projector and screen and in many cases a representative of the Commercial Department attends to tell the audience what British Railways has to offer. These displays have been given in various towns throughout Scotland to organised bodies of people such as Guilds, Schools. Women's Rural Institutes, Church Associations – in fact to any collective organisation interested in travel. During the past year, they have been seen by about 60,000 people. We have also disp1ayed fi1ms to members of the staff and recently we displayed throughout Scotland a series of films produoed by the British Transport Commission to 2,168 staff. A short time ago in Glasgow we took over a cinema for a morning perfomance and obtained an audience of about 2,100 members of the public.

While we display films by means of our own projectors, we have a most interesting job in arranging all the necessary facilities required in connection with the making of films and we are often able to assist our own organisation in taking films and also other organisations who take films on a commercial basis.

Another aspect of our work which provides some colour is the ceremonial side of' our job. In this connection, I have told you about the "Clan Buchanan". We also arrange Christmas tree displays, exhibitions in railway stations and reception of distinguished people.

You will, I am sure, be interested to know that a very large number of people who have no connection with transport whatsoever take a very great interest in everything that pertains to a railway, locomotives, steamers and railway rolling stock generally. Spotters circulate in large numbers, more particularly in the south, and even in Glasgow on the occasion of the unveiling of the "Clan Buchanan" locomotive, Mr. Riddles, the designer, had to sign several autograph books held up by small boys before he was permitted by them to leave the station.

The spotter is sometimes rather a trouble to the railway staff but this is caused by his enthusiasm for his hobby, and. I think while one may often have two minds on the subject that the young spotter should be encouraged as it leads in later years to an interest in railways.

To encourage our many friends outside the railway industry to continue the pursuit of their hobby, we arrange visits to railway installations, to railway locomotive depots and to people who have a keen and practical interest in the matter, we arrange visits over such outstanding works as the Forth Bridge. I should imagine that in a Society such as yours, the majority of you have walked over this remarkable engineering achievement and I know if you have done so, you must have been greatly impressed by the magnitude of the job. Our visitors come from all walks of life, from people in engineering and locomotive trades. lawyers, doctors and clergymen and. it is amazing to see how good the grip these men have of railway matters.

One of British Railways new ventures has been the setting up of Regional Staff Magazines. These magazines are now aged two and growing lustily so that I have no fear, unless the paper situation becomes such as to prevent us, that they will become oven better than they are today. I am glad to say the Scottish Region Magazine occupies a very high place. It is technically correct, the standard of the articles ia high, the articles are readable and the credit for this excellent result goes to the Magazine Editor, Mr. Norman McKillop, who has worked. very hard and very efficiently in the interests of his Magazine.

That, gentlemen, gives you very briefly an idea of the various and widespread ramifications of this particular part of our work but there is another side of our business again upon which I have not yet touched and that is the advertising or the bread-and-butter side.

You will appreciate it is no use running a. train, running a special excursion or arranging outings if you tell no-one about it and it is with the object of informing the public what we have to offer that the advertising side exists. The man in charge of the production side of the business has a very heavy responsibility. It is his duty to see that the la,yout is correct, that is to say, that the advertisements are presented before the public in the best way possible to attract them, and for this he must have a sound knowledge of the various fonts of type because the type must be such as to suit the message.

For our advertisements we have gone over largely to Gill Sans type but in view of the magnitudc of our business we have to spread. our advertising over many firms and many of these firms do not, unfortunately, possess a. wide range of type. They intimate to us what their stock is and we make a decision as to the best use which can be made of the type in their possession.

Into the Production Section of our Oftices comes the preparation of all those pictorla1 posters displayed on railway billboards. These necessitate a. knowledge of colour, a knowledge of layout and. a knowledge of the 1eading artists of the day. Added to that, the man in charge of the Production has to select a site after considering various angles which shows British Railways to best advantage. We are now departing f'rom the old standard of design and going in for modern treatment and I tbink in the course of a few months you will be agreeably surprised with the work which is on display.

British Railways do not advertise on1y their own facilities but they assist the holiday resorts to advertise the attractions which they have to offer to the visitors because, after all, if a large number of visitors decide to visit a holiday resort, we can confidently expeet to convey them to and from their destinations. We. therefore have joint schemes with. the resorts embracing poster, folder and newspaper advertising.

On the newspaper advertising side of the house, the man in charge has to have a detailed knowledge of his papers, of their rates, when they go to press, what his absolute deadline for the acceptance of an advertisement. Again a knowledge of typography is essential in a job such as this, because the size of type is based on a pointed. syatem of 72 points to an inch. while the width of a column is mewaured in ems, pica ems = 12 points.

It may surprise you. to know that the cost of inserting an announcement in a newspaper varies from a few shillings to about £25 for a single column inch..

If you remember that we produce posters, pictorial posters and letterpress posters giving details of the facilities run by British Railways, Timetable Sheets and Timetables. Clyde Steamer Programrnes, Circular Tour Programrnes, Holiday Run-about Ticket Programmes, Camping Grounds in Scotland and the day-to-day train services, cheap f'ares, day tickets, evening excursions and fares publicity, an appreciation will be obtained of the heterogeneous collection of material which passes through the Production and the Newspaper Sections.

I have not yet mentioned one of the heaviest Sections in the Public Relations & Publicity Department and that is the Section daeling with outdoor matters. This Section is responsible for the arranging of sites for billboards, billboards which advertise railway f'acilities and sites which are sold to advertisers to advertise their own goods. It covers the provision of station name signs and public direction signs, neon lighting of stations, the siting of various kiosks – in fact wherever alterations and improvements are carried out to a station in the Scottish Region, this Section is always in the fore. In view of the very large expenditure of money required to maintain this side of the business, the people engaged on it must have a knowledge of Parliamentary legislation covering their particular jobs and not the least of which is the Town and Oountry Plarming Act which covers the majority of outdoor display advertising today. There is scope for initiative, artistic ability and ingenuity in providing and equiping display stands and enquiry offices at shows, exhibitions and other public events.

It will be appreciated that the men in Departments such as I have indicated, have to work hard and always against the clock.

In all our work, we have been fortunate in securing the co-operation of the various Departments of the Scottish Region and our thanks are due to the Officers of these Departments for giving ot their time and their co-operation to maintain the high record which the Public Relations and Publicity Department of the Scottish Region holds today.

PAPER TO BE READ BY SIR JOHN ELLIOT, M.Inst.T., CHAIRMAN OF LONDON TRANSPORT

to

THE INSTITUTE OF PUBLIC RELATIONS SEVENTH ANNUAL CONFERENCE, MARGATE, SUNDAY, 29th APRIL 1956

------------------------------------------------------------

WHY SHOfJLD WE MIIND WHAT THE PUBLIC THINK?

What a silly question to ask! Well, I will tell you a story.

The relations of a great railway company with its public – in this case bad relations – were the cause of my entry into this curious and then uncharted business, just over thirty years ago.

A famous railway manager, Sir Herbert Walker, was very busy making plans in the privacy of the offices at Waterloo for the electrification of the line and he did not appreciate the seriousness of the complaints of his passengers about the poor quality' of the existing services. Indeed, he was not fully aware of them, because the officer whose job it was to deal with them, Fred Milton, was so far down in the official hierarchy that he never saw Walker to tell him about them. That was lucky for me, because Milton, as I soon found out, was a first-rate public relations man – 'a natural' in fact. Here's to his memoy.

One day the Southern Railway found that its annual parliamentary bill was going to be blocked by irate Members of Parliament from Kent, Surrey and Sussex. This was serious news; Walker went straight off to 55 Broadway to see his friend Lord Ashfield, to ask him how it was that the Underground with all their difficulties seemed to keep clear of tris one.

"I will tell you, Herbert", said Ashfield. "You must take much more trouble to tell people what you are doing, and why, and tell them before the difficulties appear. Take them into your confidence, add them to the team. I am told that newspaper reporters can get no help from Waterloo, so of course they go elsewhere and pick things up as best they can, and nearly always to your disadvantage. What you need is an interpreter – someone who knows Fleet Street, and whom you can rely on to advise you how to deal with journalists."

I had left the "Evening Standard" a few months earlier, and was thinking about retiring at the age of 26 when Lord Ashfield sent for me and told me he had recommended me for the Southern job. A week later, on a cold foggy morning in December 1924, I sat by the fire in Walker's room and the conversation went something like this.

"Well, Elliot, Lord Ashfield tells me you can manage the Press."

"No, sir, I don't think that is right. The Press will continue to manage themselves."

"Well, what can you do then?"

"You must tell me first what you want me to do. Are you serious about this, or do you merely want to get out of a temporary trouble?"