|

John Ramsbottom: locomotive engineer |

| Professional papers Patents

|

|

John Ramsbottom: locomotive engineer |

| Professional papers Patents

|

Biography

Robin Pennie has produced an excellent

biography. John Ramsbottom was born in Todmorden, Lancashire, on 11 September

1814, the son of a cotton spinner who owned the only steam-driven mill in

the area. He was educated by local school masters and Baptist ministers.

His practical training started at his father's mill, where he was given a

lathe and built small working steam engines. He then rebuilt and re-erected

the beam engine at his father's mill and invented the weft fork, later adopted

universally, which enabled looms to be worked at high speed. He was an active

and enthusiastic member of the Todmorden Mechanics' Institute, showing quick

perception and ability in all mechanical matters.

In about 1839 he went to Manchester and joined

Sharp, Roberts & Co., who had a

high reputation as builders of locomotives and cotton spinning machinery.

Here he gained experience in locomotive building and his ability sufficiently

impressed Charles F. Beyer, in charge of the

locomotive department, so that in 1842 he recommended Ramsbottom as locomotive

superintendent of the Manchester and Birmingham Railway, which in 1846 became

part of the London and North Western, of which he was then appointed district

superintendent of the North Eastern Division. In 1857 he was

promoted to locomotive superintendent of the Northern Division, covering

all routes of the LNWR north of Rugby, at Crewe works.

Ramsbottom was a first-rate organizer, a brilliant inventor, and he

had an endearing personality. His first important contribution to the locomotive

engineering world was the double-beat regulator valve. This was introduced

in 1850; it was followed two years later by the split piston ring

and the ancestor of the modern mechanical coaling plant; and in 1856

(see Patents below) by the displacement lubricator and the safety valves

which bear his name. Towards the end of 1858 appeared the first of

his celebrated 'DX' 0-6-0 goods engines, of which altogether 943 were

built, representing one of the earliest examples of mass production. They

were provided with screw-reversing gear, yet another Ramsbottom

invention.

Griffiths tells a story (which he stated is almost

"folklore") of a meeting between Bessemer and Ramsbottom in which the former

advocated the use of Bessemer steel for rails, to which the response was

reply is supposed to have been 'do you wish me to be tried for manslaughter?'

And it was only after rigorous testing that Ramsbottom permitted trials of

steel rails (earlier steels had been too hard and brittle for use in rails).

Following this a Bessemer plant was installed at Crewe

Works.

In 1859 he built the first of his 2-2-2 type express locomotives,

two of which took part in the railway 'race' between the East coast and Westcoast

companies from London to Edinburgh in 1888, and in 1863 he developed the

2-4-0 type for use over more heavily graded routes.

In 1862 Ramsbottom became all-line chief mechanical engineer of the

LNWR, Britain's largest railway, with locomotive construction concentrated

at Crewe works. His mechanical and organizing abilities were given full scope

during the rapid development of these works, where he introduced Bessemer

open-hearth steel-making. In 1868 he installed Siemens-Martin furnaces. He

reduced the number of individual locomotive types and standardized their

components to the greatest possible extent, and new machine tools and equipment

ensured accuracy in manufacture and facilitated transfer of components within

the works The result was a more than twofold increase in the rate of locomotive

production.

He was the inventor of water pick-up troughs laid between the rails,

whereby a scoop lowered into the trough from the locomotive or tender allowed

additional water to be picked up whilst the train was running, thus making

possible much longer non-stop runs. First applied in 1860, this was rapidly

extended to most British and some American and French main-line railways.

In 1870 locomotive haulage replaced steel-rope haulage of trains up the steep

gradient from Liverpool, and Ramsbottom designed ventilating extractor fans

to remove foul air and smoke from the tunnel.

Ramsbottom retired in 1871, having been responsible for the

construction of 1,035 locomotives at Crewe since his appointment fourteen

years previously. In 1871 he retired from the LNWR. In 1883 he became consulting

engineer and subsequently a director of the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway,

where he was responsible for the design and construction of their Horwich

(Bolton) locomotive works and was chairman of the rolling-stock and locomotive

workshop committees. He was also a director of Beyer, Peacock, & Co.,

locomotive builders, a firm in which his two sons held important positions.

He died in 1897, when many of his inventions were still in use on

the more modem engines designed by his famous successor, F.

W. Webb.

A modest and kindly man, he took a great interest in technical education

and was a governor of Owens College, Manchester, where in 1873 he endowed

the Ramsbottom scholarship for young men in the locomotive department of

LNWR. He was a founder member of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers

in 1847 and its president in 1870-1. He was a member of the Institution of

Civil Engineers from 1866 and received the honorary degree of M.Eng. from

the University of Dublin. Ramsbottom died on 20 May 1897 at his home

in Alderley Edge, Cheshire, and was buried in Macclesfield cemetery.

Reed's major account of Crewe Works

amplifies the above concise notes:

Ramsbottom was possibly the most remarkable engineer ever to be connected

with Crewe works. He was born at Todmorden, the son of a small cotton spinner

who owned the first steam-driven mill in the valley. John had little in the

way of schooling, being trained by and worked for his father, but he schemed-out

and made other machinery for the district, and at the age of 20 took out

a patent in conjunction with his uncle, Richard Holt, for the improvement

of power looms to weave two pieces of fabric at one time. His first 24 years

were spent in his birthplace, after which he went as a journeyman on textile

machinery to the Manchester works of Sharp Roberts, where he came under the

influence of two outstanding men, Richard Roberts and Charles

Beyer. From them probably came his appreciation of accurate

measurement and its application to batch production. Eight of his testimonials

from residents of the Todmorden area dated 1839 still survive, and everyone

mentions the reliability of his character.

At Sharp Roberts he must have been drafted early onto locomotive work,

and there he attracted the notice of Beyer, who had the locomotive side in

his hands. Some three years later a recommendation from Beyer helped Ramsbottom

to get the job of locomotive running foreman, under the engineer, of the

newly-opened Manchester & Birmingham Railway, though he had no experience

of railways at all. He took up this position in May 1842, and was promoted

to take charge of the locomotive and rolling stock department of the MBR

at œ170 a year in November 1843 when that section was separated from

the chief engineer's department.

He retained that position when the MBR was absorbed into the LNWR,

and when the lines between Manchester and Leeds were opened in 1849 the engines

also came into Ramsbottom's charge as part of the new North Eastern Division

stock — his salary was advanced to £500 a year from £300,

and in 1853 was stepped up to £850. The LNWR board thought so well of

him that in 1856 he was given charge of the rail rolling mill at Crewe, though

his headquarters continued at Longsight, Manchester. During his time on the

NED he took out nine patents, including the split piston ring (1855),

safety-valve (1856), feed pump, turntables, hoists for raising and lowering

locomotives, and a coal hoist.

He was made locomotive superintendent of the combined Northern and

North Eastern Divisions of the LNWR in 1857, and in 1862 became the first

all-line locomotive superintendent at a salary of £2,000 a year, increased

to £3,000 as from 1 January 1864 and to £5,000 from 1 January 1869,

a reflection of the greatly increased responsibilities, including the steel

plant, he was holding and the amazingly good job he was making of them. These

salaries set the pace for the 19th century chiefs at Crewe; Cawkwell, the

LNWR general manager from 1858 to 1874, never had more than £3,000 a

year, nor did his successor, George Findlay, ever rise to the £5,000

level in the next 18 years. Ramsbottom's salaries also began the enormous

gap between the remuneration of No 1 in the locomotive department and those

of the various Nos 2, none of whom had more than 20 percent of the chiefs

salary. This big gap continued to the end of the LNWR and in later years

caused trouble in the line of succession. Much of the work done by Ramsbottom

at Crewe is detailed in Chapter 5; extensions of it included the mechanical

ventilation of Edge Hill tunnels at Liverpool in 1871 when endless-rope haulage

was replaced by locomotive power, the solution being based on a Ramsbottom

patent of March 1869.

Largely through the enormous amount of work that he did for over a

dozen years, and the strain of accomplishing it to the satisfaction of himself

and Richard Moon, he began to wear out in 1870, and the stress became more

intense in the summer and autumn by his presidency of the Institution of

Mechanical Engineers, though he gave no presidential address, and by the

death of the then Crewe works manager. In September 1870 he told the Board

he would have to retire at the end of twelve months, and his absences became

more prolonged in 1871. For some years after the end of September 1871 the

LNWR board retained him as consulting engineer at £1000 a

year.

The complete release from the immense day-by-day administrative task

and the large extensions of Crewe Works and the locomotive department made

the cure. By 1875, at 60 years of age, he was back to full health and vigour,

and remained a hale and hearty man with firm lines for another 20 years.

He took up outside consulting work, though he was already wealthy from his

large salary and patent royalties. Altogether he took out 40 patents, but

only three of them came after his retirement from Crewe. Nine were related

to steel and steel-making; six, over 14 years, were to do with fluids. The

first of them in 1851 resulted from his suggestion to the LNWR board in January

1849 of fitting a cheap apparatus in the nature of a gas meter, to record

mileage and speed run by each engine."

In 1883 he was appointed consulting mechanical engineer to the LYR,

where in collaboration with Barton Wright, the locomotive superintendent,

he planned the new Horwich works and specified its equipment. On the death

of Lord Houghton in 1885 he was elected a director of the LYR and became

chairman of the locomotive committee, in which position he greatly influenced

and supported his old apprentice John Aspinall, who had succeeded Barton

Wright. [This period is covered in great

depth by H.A.V. Bulleid in his biography of Aspinall). He resigned only

in 1896 on account of age. Also in 1883 he became a director of the Beyer

Peacock private company, formed some years after the death of Charles Beyer

had terminated the original partnership. Here he strengthened the close relations

he had maintained with Gorton Foundry from its inception in 1855.

One cannot record that Ramsbottom was a nepotist, and he promoted

no one above his capacity; yet he had a strong family feeling and helped

his sons, cousins and nephews into jobs, but thereafter left them to make

their own way. His sons, John Goodfellow and George

Holt, were trained at Gorton Foundry in preference to Crewe from 1880

and 1884. Both remained with Beyer Peacock until February 1900, attaining

increasingly responsible positions.Ramsbottom's younger cousins,

Frank Holt (1825-93) and

Charles Holt (1830-1900) also were in locomotive

work. The former began an apprenticeship with Sharp Roberts and Sharp Bros

before Ramsbottom left, and later went to Crewe, and while there was put

in charge of the South Staffordshire Railway locomotive working as Trevithick's

representative while the ND had oversight. Later he was for a short time

in India, and then was with Beyer Peacock, R. & W. Hawthorn, and the

Midland Railway, and was works manager at Derby until he died. He was credited

with the initiation of steam sanding. His brother Charles was works manager

at Gorton Foundry from 1877 to 1900. Robert Ramsbottom Lister, son of one

of John Ramsbottom's sisters, was taken on as an apprentice at Gorton Foundry

in 1869 and remained with Beyer Peacock all his working life, being

chief draughtsman 1890-1900 and works manager April 1900. A second nephew,

Frederic John Ramsbottom Sutcliffe, became a Crewe apprentice in 1860, and

as a result of his experience at the original 'melts' he went into the private

steel industry and became well known.

John Ramsbottom's principal characteristic was supreme competence.

He was a completely objective man, and though well aware of his worth he

was not egotistic. His manner was pleasant; he had no vanity, and no one

laughed more heartily than he at Wodehouse's quip at the farewell Crewe dinner

in 1871 that the new home of Mr Ramsbottom had hitherto been the property

of a Mr Sidebottom and was situated at Broadbottom. Cusack Roney in 1868

described him as "the earnest, persevering, never-tiring John Ramsbottom."

He had the ability to pick good subordinates from the choice available, and

once he had trained them to his ways and became confident that they could

stand the pace, he did not trouble them from day to day, and he saw to it

that they had regular increases in salary. From his humble beginnings he

rose not only to pre-eminence in the world of mechanical engineering, but

also one day entertained the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII) to luncheon

in his house near the works after Edward had made a tour of the shops in

January 1866. This was at a time when there was more social protocol than

in later years, and before Lord Richard Grosvenor (later Lord Stalbridge)

had joined the LNWR board and brought a succession of distinguished visitors

to Crewe.

On his retirement Ramsbottom was entertained formally by the LNWR

board at Euston Hotel. Among those present at the dinner were the Lord Mayor

of London, the Duke of Buckingham, who (as the Marquis of Chandos) had been

LNWR chairman 1855-60, a critical period in Ramsbottom's career, Charles

Beyer and Sir Joseph Whitworth. In 1873 Ramsbottom donated £1,000 to

Owens College, Manchester, to found a two-year scholarship for LNWR locomotive

department employees under 21 years. Another event ofhis time at Crewe was

the naming ofa new street after him; in 1872 Webb named one of the new express

2-4-0s in his honour. Ramsbottom was a founder member of the Institution

of Mechanical Engineers, and when he died at Alderley Edge on 23 May 1897

only two founder members remained: his friend Peter Rothwell Jackson of the

Salford Rolling Mills and Richard Williams of Wednesbury. A year or two after

his death a memorial window was put into the then new chancel of Christ Church,

Crewe. Ramsbottom's estate was proved at the large sum of £144,372,

but he made no bequests outside the family, nor was he known to contribute

to organised charities. The silver plate given him by the company when he

retired was much prized, and he left it specifically as a family

heirloom.

In 1860, at the close of his career, John Ramsbottom was awarded an

honorary Master of Engineering degree by Dublin University. The tendency

of outstanding British locomotive designers to get their engineering degrees

after their life's work was finished, and honoris causa too, explains a lot

about British locomotive design. Or rather, it explains why Britain fell

behind more academically-conscious nations as soon as the pioneering phase

was over. Ramsbottom might in fact be described as the last of the great

British locomotive engineers. By the time he retired most of the inventions

and innovations which could be developed by shrewdness and mechanical intuition

had made their appearance, and it was the theoreticians armed with an academic

approach who would make the next real advances. England's Churchward was

perhaps an exception, but apart from him it was non-British engineers with

years of academic study behind them who set the pace: the American Professor

Goss, the German Professor Schmidt, and that keen student of thermodynamics,

Andre Chapelon. What happened when a theoretician without academic training

got into the saddle would be shown by Ramsbottom's successor, Webb, whose

pursuit of a valid improvement (compounding), combined with an inability

to make use of evidence in a scientific way, led to the construction of hundreds

of deficient locomotives on the London & North Western Railway. Ramsbottom

was born near Manchester in 1814 and acquired his initial engineering experience

working for Sharp, Roberts, & Company; the same firm which had set Charles

Beyer on the locomotive-designing road. The early forties were a good period

for engineers in search of rapid advancement, and at the age of twenty-eight

he secured the job of managing the Longsight Works of the Manchester &

Birmingham Railway, a company which soon afterwards became part of one of

Britain's major railways, the London & North Western. Thus in 1846 Ramsbottom

was distinct locomotive superintendent of the LNWR.' s North Eastern Division.

The following year he gained additional distinction by reading a paper on

boilers to the first meeting in Birmingham of the newly-founded Institution

of Mechanical Engineers. Although he had introduced a new type of regulator

(the L.N.W.R. 'double-beat' regulator) in 1850,

Ramsbottom's first major invention was the split piston ring. This

was astonishingly successful and was adopted throughout the world. The problem

of establishing a reliable and long-lasting steamtight fit between the piston

and the cylinder wall had hitherto been unresolved. Ramsbottom's solution

was to cut circumferential grooves in the piston, into which were fitted

narrow cast-iron split rings. The rings were split to enable them to be opened

out when being fitted to the piston. They had to be held in the closed position

as the piston was reinserted in the cylinder, after which their natural

elasticity held them tight against the cylinder wall, their natural diameter

being one tenth greater than the piston. Several rings were fitted to a piston,

in order to cope with any slight irregularities in different parts of the

cylinder. On trial, Ramsbottom found that his rings could do over three thousand

miles before renewal. Moreover, with these rings the weight of the piston

could be halved.

In 1856 Ramsbottom introduced his sight-feed lubricator, a boon to

LNWR. enginemen, and the safety valve still known throughout the world as

the Ramsbottom valve. The latter consisted of two parallel pipes which projected

vertically from the top of the boiler and, between them, a coiled spring

which pulled down a beam on to the two valves at the top of the pipes. These

valves lifted equally and were so well balanced that when blowing-off pressure

was reached in the boiler the initial reaction of the valves was to vibrate,

producing a recognizable hum.

In 1857 Ramsbottom was appointed L.N.W. locomotive superintendent

at Crewe. In 1859 he appointed Webb as his chief draughtsman, and it was

Webb who was responsible for most of the design work on Ramsbottom's locomotives.

Ramsbottom realized that a 2-4-0 passenger and 0-6-0 freight locomotive could

handle the bulk of the Railway's traffic, and built large numbers of these

types, which continued to be built, with alterations, by his successor Webb.

It was these basic 2-4-0 and 0-6-0 types that were still doing much of the

work in Edwardian times, Webb's later designs having proved so unsatisfactory.

Ramsbottom's standard freight machine (class DX) was produced in numbers

very large by contemporary standards; 943 units were built, and Webb based

his own 0-6-0 on this design. In general, Ramsbottom did not believe in building

engines large enough to handle the biggest loads likely to be encountered.

He preferred to design for the average task, with the result that his locomotives

were often worked much harder than on other lines. This set up something

of a tradition, subsequent LNWR locomotives being liable to severe 'thrashing'

by their drivers, yet designed to stand up well to such treatment. His

locomotives, while setting a tradition, themselves owed much to the tradition

of their predecessors; the 'L.N.W.R. look' had already been established and

the simplicity and exterior balance of Ramsbottom's designs did nothing to

detract from it. However, he did spoil the appearance of his machines by

his fondness for crazy fretwork; the chimney caps of his locomotives had

pieces cut out of them for the sake of what Ramsbottom called decoration.

The pieces which he cut out of his driving wheel splashers were less hideous,

and were sometimes appreciated by enginemen looking for a place to direct

their oil-cans. In common with most, but not all, of his contemporaries he

offered little comfort to his enginemen. The very successful class of 0-6-0

saddle tank that he designed for yard work had screw reverse: for most purposes

this was superior to the conventional lever reverse but, because it needed

more time to operate, it was quite unsuited for locomotives whose main work

was stopping, starting, and reversing. Again, Ramsbottom refused to provide

his enginemen with a roof over their heads at a time when other designers

had accepted the possibility that wet men might not work so well as dry men.

The truth is that Ramsbottom was a hard man in a hard age. Indeed, his

predecessor Trevithick had been pensioned off precisely because he was too

kind-hearted. It is likely that Ramsbottom bears the responsibility for the

autocratic and repressive tradition which established itself at Crewe in

the last decades of the century.

In many ways Ramsbottom's most spectacular invention was the water

trough. He liked small and rather flimsy tenders, so when he was faced with

an acceleration of the Irish Mail, which was to run non-stop between Chester

and Holyhead ( eighty-five miles) in 125 minutes, the idea of a device to

pick up water at speed had an obvious attraction. He decided that a long

track pan between the rails, with the water regulated to maintain a 5in.

depth, would be the best solution. A scoop lowered from the tender would

dip 2in. below the water surface, leaving a 3in. clearance for contingencies

(like stone ballast in the trough or weak springing on the tender). Ramsbottom

estimated that at 15 m.p.h. the scoop would lift the water 7ft 6in., and

on the first trial, in which the vertical pipe from the scoop into the water

tank ended 7ft 6in. above water level, he had the satisfaction of noting

that at 15 m.p.h. the water was propelled to the very top of the pipe, and

stayed there, without overflowing into the tender tank. These tests showed

that 40 m.p.h. was the best speed for pick-up, 1,150 gallons being taken;

faster and slower speeds resulted in a smaller intake. In order that the

engine crew might maintain the optimum speed over the quarter-mile trough

which he had laid at Conway in North Wales, he fitted a locomotive speedometer

(or 'Velocimeter' , as he called it), that he had earlier devised. This consisted

of oil inside a glass tube, mounted vertically. The tube was rotated by a

cord actuated from the rear axle. As the axle rotated faster, so did the

tube, causing the top surface of the oil to become more and more concave.

A scale was engraved alongside the tube, by which the bottom of the concave

surface marked the speed in m.p.h.

Most of Ramsbottom's period as top man at Crewe was devoted to improving

the organization of the works. He introduced strict standardization of parts

and of gauges. A Bessemer, and later a Siemens-Marhn, steel plant was introduced,

and an 18in. gauge steam railway linked the various parts of the works. Among

other innovations were cast iron locomotive wheels with H-section spokes,

much used on successive generations of LNW. freight locomotives, a horizontal

steam hammer, and various improved tools. He retired in 1871 at the age of

fifty-seven, in the belief that his health was failing. In fact he lived

another quarter-century, during which he became a director of Beyer, Peacock

and of the Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway. He did much of the planning

in connection with the latter company's new locomotive works in Horwich.

His two sons reached high positions in Beyer, Peacock. It has already

been remarked that Ramsbottom was virtually the last of the great British

locomotive engineers, because after him the lack of academic training began

to hold back men who might otherwise have made great contributions. There

is a lot which can be said against the British tradition of training engineers

on the job. Years of rather boring 'experience' on the shop floor must have

driven many bright young men away from the railway service, and dulled the

brilliance of those who slogged it out. Lack of academic training, other

than attendance at night courses at the end of a hard day's work, must have

meant that good ideas lacked the theoretical underpinning that could have

ensured their success. On the other hand, it is also true that the better

British locomotive designers, because of their type of training, were excellent

organizers of production. In this sense Ramsbottom is again something of

a landmark. His inventions were almost entirely devised before he became

locomotive superintendent, and after coming to the top position his most

important work was not design and invention but production and administration.

In this he resembled most chief mechanical engineers, and for this work the

traditional non-academic training of British engineers was probably the most

advantageous.

In 1868 Sir Cusack Roney wrote respecting Mr. Ramsbottom

(cited Rly Mag., 1899, 5,

232)

"At the head of the mighty establishments at Crewe. . . . is one man who,

if he had been in Egypt, with works not a quarter the size and not half so

ably carried out, would have been at least a Bey, or more probably a Pacha;

in Austria a Count of the Holy Empire; in any other country in the world,

except England, with crosses and decorations, the ribbons of which would

easily make a charming bonnet of existing dimensions. But in England, the

earnest, persevering, never tiring JOHN RAMSOTTOM is – John

Ramsbottom."

Rogers (biography of Chapelon): John Ramsbottom of the London & North Western Railway was one of the greatest locomotive engineers of his day. His DX class 0-6-0 goods engines, which were built from 1858 to 1872, numbered more than any other steam locomotive class in British history. The DX was an extremely light engine which could run anywhere on the system and it had the screw reversing gear which Ramsbottom was the first engineer to use. He produced a noteworthy class of 2-4-0 express locomotive which as continued and modified by his successor Webb made the fastest running in the railway races from London to Aberdeen in 1895. Because, at the time these engines first appeared in 1866 many engineers held that only engines with single driving wheels were suitable for fast running, it is likely that Ramsbottom had discovered that a good steam circuit was of greater importance.

Carpenter, George W. biography

Oxford Dictionary of National

Biography

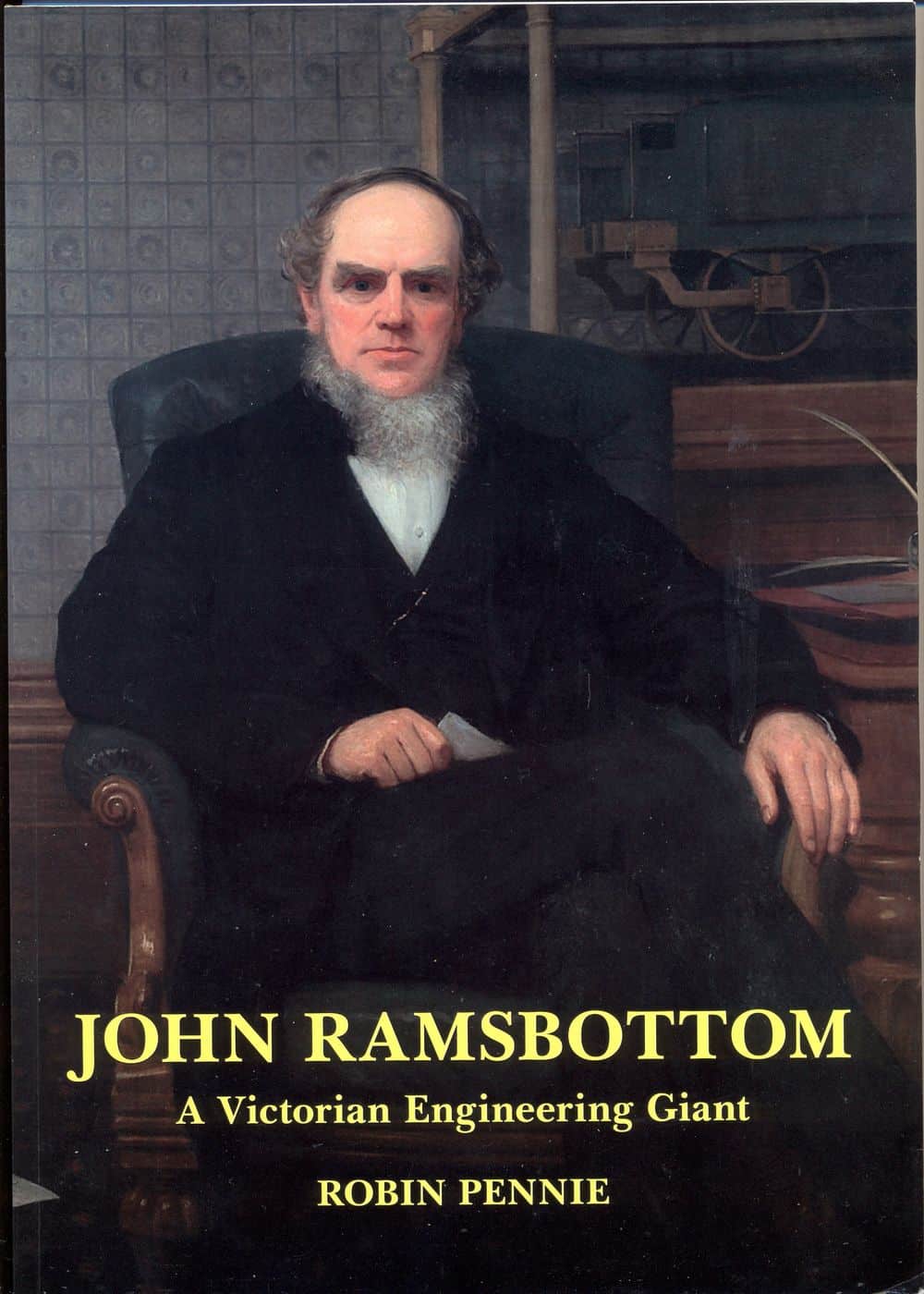

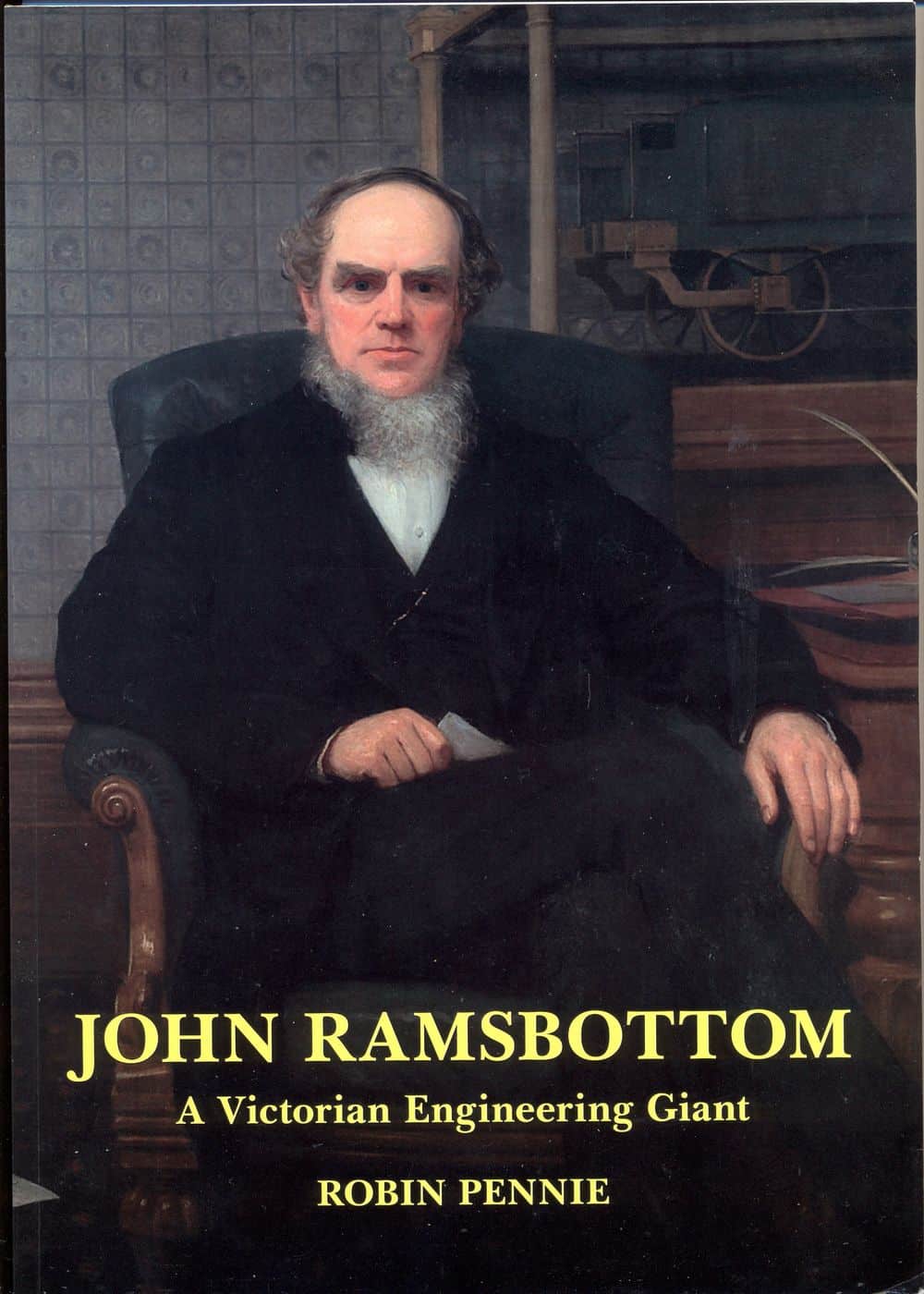

Pennie, Robin. John Ramsbottom:

a Victorian engineering giant. Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway Society,

2007. 96pp

Proceedings of the Instn Mech. Engrs. 1897,

52. 236-41 Obituary.

Min. Proc. Instn Civ. Engrs, 1896/97, 129, 382. Obituary

H.A.V. Bulleid, The Aspinall

Era.

R.S. McNaught. The influence of John

Ramsbottom. Rly Wld, 1957,

18, 97-103.

Very brief biography: mainly his inventions: double-beat regulator,

split piston rings, water troughs and associated pick-up mechanism (and diversion

to note fishes in water troughs), and safety valves. Also 2-2-2s named after

Ramsbottom's daughters Edith and Eleanor and Whale transferred

the names to Precursor class

Nock, O.S. Railway enthusuast's

encyclopedia

Talbot, Edward An illustrated history

of LNWR engines. 1985.

W. A. Tuplin, North Western Steam (1963);

Hambleton, F.C.John Ramsbottom: the father of the modern

locomotive. 1937.

Ottley 2863: notes that partly a reprint of material in J. Stephenson

Loco. Soc., 1937, February. Only 30 pp..

John Ramsbottom. Locomotive Carr. Wagon

Rev.,1941, 47, 143-7; 178-82.

Supplement to earlier work??

Nature of Ramsbottom household (including 6 children - one aged two

- the great man was 66) in Alderley Edge from 1881

Census: Backtrack 14,

637.

On an improved locomotive boiler.

Proc. Instn. Mech. Engrs.,

1849, 1, 1-11 (25 July)

Description of an improved locomotive boiler, in which it was sought

to obtain by means of a separate steam-chamber a larger flue area and larger

heating surface, with less relative bulk and weight, and with great simplicity

of construction.

Description of an improved coking crane for supplying locomotive engines.

Proc. Instn. Mech. Engrs.,

1853, 4, 122-5.

A device to assist the loading of tenders with coke.

On an improved piston. Proc. Instn.

Mech. Engrs., 1854, 5, 70-4.

Steam leakage had been a problem and Ramsbottom devised a means for

sealing the piston against the cylinder wall without increasing friction.

Ramsbottom's arrangement comprised a piston with three grooves. Packing rings

of brass, steel or iron could be inserted into the grooves, but the important

aspect was that the rings had to be made such that they would spring outwards

by a small amount. It was that spring which caused them to press against

the cylinder wall and so effectively seal the piston. Over the intervening

years nothing better has been found; although several variations have been

developed, they are still fundamentally Ramsbottom rings. By the time he

presented the paper, the first pistons as described had been at work for

16 months without any trouble and 15 other locomotives had been similarly

fitted. Ramsbottom considered that a set of rings would last for 3,000 to

4,000 miles.

On the construction of packing rings for pistons.

Proc. Instn. Mech. Engrs.,

1855, 6, 206-08.

The writer had invented a a metallic piston, as described in

Proceedings 1854,

5, 70), where the packing is forced against the working surface

of the cylinder by its own elasticity, and owing to its being comparatively

slender in cross section, had to be left about 10% larger in diameter than

the block of the piston, in order to give the requisite pressure for preventing

the passage of steam. It was found, that when such packing was made of a

circular figure before being compressed, it was invariably worn more rapidly

at the joint, and at the part opposite. It is very natural that this should

he the case, and it has been the practice with many engineers, when using

packing rings which are pmssed against the cylinder by their own elasticity

alone, to make the part opposite the joint, where there is clearly the most

strain, stronger than any other, each half being tapered off to the joint

; although the writer is not aware that this has been done by any positive

rule.

It was taken for granted that the unequal wear above referred to was owing

to the pressure against the cylinder being unequal in different parts of

the ring, and as the packing rings used by the writer are made of wire or

drawn rods, and consequently uniform in thickness, it was found impracticable

to ensure this equable pressure by tapering the ring, but as this uniform

pressure can be obtained by making the packing ring truly circular in figure,

but unequal in thickness it oocmred to the writer, inasmuch as the rings

which he employs are bent and not turned, that the same elld might be gained,

by conversely making the ring equal in strength of material but unequal in

figure or that a ring might be made of such a shape, that although uniform

in cross section, it would press equaly against the working surface of the

cylinder all round.

On an improved safety valve. Proc.

Instn. Mech. Engrs., 1856, 7, 37-47..

The tamper-free duplex safety valve. It was not unknown for locomotive

drivers to load their safety valves in order to obtain increased boiler pressure

so that they could make up lost time. Such practice was dangerous and a number

of boiler explosions were attributed to it. Ramsbottom's safety valve design

prevented any loading which would result in an increase of boiler pressure,

but did allow pressure to be released by means of a lever which had contact

with both valves.

Description of a method of supplying water to locomotive tenders whilst running.

Proc. Instn. Mech. Engrs.,

1861, 12, 43-50. Disc.: 50-2. Plates 10-13.

The length of trough laid on the Chester and Holyhead Railway near

Conway was 441 yards in the level. The trough contained water 5 in deep,

and the scoop dipped 2 in. into the water, leaving a clearance of 3 in. at

the bottom of the trough for any deposit of ashes or stones. The maximum

amount of water was raised at a speed of about 35 miles/hour, when the quantity

raised amounts to as much as the above theoretical total.

On the improved traversing cranes

at Crewe Locomotive Works. Proc. Instn. Mech. Engrs., 1864, 15,

44-58.

On the improved traversing cranes at Crewe Locomotive Works. 44-58.

The traversing cranes were employed in the locomotive shops of the London

and North Western Railway at Crewe, where they were designed and erected

by Ramsbottom. They were seen in action by the members during their visit

to the Crewe works in the excursion at the Liverpool meeting of the Institution

in summer 1863. From the interest manifested in them on that occasion and

the numerous enquiries that have since been made respecting them, the writer

has thought that ft description of the principle and construction of these

cranes may be acceptable to the members. There were seven of these cranes

in use at the Crewe works, which had been working successfully for some time,

the first having now been three years in constant work. They were driven

by power and are so constructed as to be driven by a light endless cord of

small diameter, extending throughout the entire length of the shop traversed

by the crane. This cord is driven at a very high speed, nearly 60 miles an

hour; in consequence of which only a very light driving pressure is required

on the shifting gear of the crane. The driving cord is kept in uniform tension

by the action of a constant weight ; and is arranged so as to allow of the

cranes working and traversing in every direction without sensibly affecting

the length of the cord. The cranes were of two classes: Longitudinal Overhead

Traversers, of which there were two pairs in the engine repairing shop, lifting

loads up to 25 tons; and Traversing Jib Cranes, of which there was one pair

in the wheel shop, lifting 4 tons. The cranes were all driven by endless

cords running along the top of the shops close to the roof tie-beams. The

overhead traversers were worked in each case by a man seated on a platform

attached to the crab and moving with it ; and the jib cranes by a man standing

below at the foot of the crane and walking along with it when traversing:

each man having control over all the lifting, lowering, and traversing movements,

by a set of handles.

Description of an improved reversing rolling mill.

Proc. Instn Mech. Engrs,

1864, 17, 115-29 + Plates 34-42.

The improved reversing rolling mill had been in operation for seven

months at the Steel Works of the London and North Western Railway at Crewe.

The special point in the arrangement was that the rolls were driven direct

by the engine, without the intervention of a flywheel; and the engine and

rolls together were reversed each time that a heat is passed through, the

rolling being alternately in opposite directions. The idea of reversing a

train of rolls by reversing the engine at each passage of the heat through

the rolls was first suggested by Nasmyth, but had never to the writer’s

knowledge been carried out before,

On an improved mode of manufacture of steel tyres.

Proc. Instn. Mech. Engrs.,

1866, 17, 186-98

The object was to reduce the waste of material in the process to so

small an amount as to leave its effect insignificant upon the cost of production,

and upon the calculation of the weight of ingot required for producing a

tyre of given dimensions. Another object was to reduce the time of manufacture,

thereby reducing the proportionate cost of plant by turning out more work

in the same time

Description of a 30-ton horizontal duplex hammer.

Proc. Instn. Mech. Engrs.,

1867, 18, 218-31.

The hammer was designed to forge large masses of steel in the Bessemer

Steel Works of the London and North Western Railway at Crewe. The first intention

was to put down a 30-ton vertical hammer of the ordinary kind; but as this

would have reqiured a 300 ton anvil, the practical difficulty and cost of

dealing with so large a mass suggested that the prinoiple of action and reaction

might afford a solution of the problem. Hence arose the conception of two

hammers acting in opposite directions; and as a matter of convenience it

seemed better to lay them on their side and cause them to operate horizontally

upon a bloom placed between them. As this idea grew into form it appeared

to present advantages both in economy and convenience sufficiently important

to warrant the construction of an experimental hammer of 10 tons. This when

brought into operation proved to possess the advantages expected; and in

consequence the writer designed and laid down the 30-ton hammer.

Mechanical ventilation of Liverpool passenger tunnel.

Proc. Instn. Mech. Engrs.,

1871, 22, 22-35. ; 66-74; 184-99 + Plates 1-6; 17.

The LNWR left Liverpool via a 2035 yard Tunnel, of mean sectional

area of 430 feet2, on an average gradient of 1 in 97. During the

thirty-three years that had elapsed since opening this portion of line in

1837 traffic through the tunnel was worked by endless rope and a pair of

winding engines at the top of the incline. All trains coming up the tunnel

from the Liverpool station were attached to the rope and hauled up by the

winding engines; trains in the reverse direction were controlled by the addition

of very heavy brake-trucks. Delays occurred through stopping every up train

at each mouth of the tunnel, to attach and detach the rope. This caused problems

during the excursion season, when trains leaving Liverpool were often so

heavily loaded that they were divided into two portions, each portion being

hauled up the tunnel separately, and the train re-united at the top of the

incline. These delays, together with the increasing requirements of the ordinary

traffic, at length induced the directors to determine to remove the rope

and winding engines, and to work the tunnel by locomotives in the ordinary

manner; but the employment of coal-burning locomotives in a close tunnel

nearly It mile long, intimately connected at each end with passenger stations

of great importance, was of cotirse impracticable without a thorough and

constant artificial ventilation. .

Contributions to other's papers

Siemens, C. William. On Le

Chatelier's plan of using counter-pressure steam as a break [sic] in locomotive

engines. Proc. Instn Mech Engrs., 1870, 21, 21-36. Disc.: 51-4

+ Plates 1-5.

Counter-pressure steam brake:. On the Tredegar and Abergavenny line

in South Wales there was a descent of 1000 feet within a distance of only

8½; miles, giving a mean gradient of 1 in 45, and the difficulty of

taking the trains down that part of the line was found to be practically

even greater than getting them up; and in this case he was looking to the

application of the counter-pressure working for surmounting to a great extent

the difliculty at present experienced. In applying the counter-pressure steam

for ordinary stoppages at stations, the quantity of injection water required

to be turned on would of course diminish as the speed became reduced; and

he wm prepared therefore to anticipate some difliculty in this application

of the plan, as the regulation of the jet would probably require a, nicety

of adjustment that waa scarcely to be expected from the ordinary class of

engine drivers. Another application mentioned in the paper of the

counter-pressure working was for shunting at stations, the regulator being

kept open the whole time, and the shunting being effected entirely by the

reversing lever ; and in order to carry this plan out, it was necessary not

only that the screw reversing gear should be employed, but also that the

engine should be fitted with good balanced slide-valves ; otherwise it was

certain the men would still continue to shut off the steam before reversing,

in order to render the reversing easier. In the experiments on the Buxton

line it had been mentioned that the steam had been shut off in order to reverse

the engine, and it was-clear the regulator had been used largely in the trials;

and the men would not be got to desist from employing it extensively until

the reversing was rendered as easy with the steam full on as with it shut

off, which it appeared to him could not be readily accomplished.

In regard to the excess of pressure shown above the boiler pressure in the

counter-pressure diagram that was exhibited from the experiments on the South

Western Railway, the explanation which had been offered, viewing the column

of steam in the steam pipe from the regulator to the cylinders as performing

the part of a ram, appeared to him to be corroborated by the circumstance

of the engine being an outside-cylinder one with separate steam-chests and

forked steam-pipe, increasing considerably the distance from the regulator

to either cylinder. In an inside-cylinder engine, where the total length

of the steam-pipe would be less, and where also the action of one piston

might perhaps interfere somewhat with that of the other in forcing the steam

back into the boiler, in consequence of the . two cylinders having only a

single steam-chest common to them both, it was probable the excess of

counter-pressure might not be quite so great as in the diagram shown. Another

reason that would account for the high pressure observed in the cylinder

was the greater density of the counter-pressure vapour which had to be forced

back by the piston into the boiler if it was not boiler steam alone, but

a wet vapour largely charged with water from the water jet, which would therefore

move more sluggishly through the passages to the boiler. That the momentum

of the boiler steam rushing into the cavity of the cylinder would be great

enough to produce a considerable rise of pressure in the cylinder above the

boiler pressure appeared to him a reasonable supposition; and he remembered

hearing a somewhat analogous circumstance, that in gunnery it was it well-known

fact that when a charge was not rammed home the strain upon the gun in firing

was more severe, producing a greater expansion at the breech.

Patents (non-railway inventions shown with green numbers: following Carpenter's ODNB biography: Ramsbottom's screw reverse appears to be missing). Earlier versions of this web page listed patents which are not in Pennie and were by other "John Ramsbottoms": following contact from Robin Pennie these have been deleted.

6644/1834: 12 July 1834: Construction of

power looms for weaving cotton and other fabrics materials into cloth or

other fabrics. (also Woodcroft)

6975/1836: 6 January 1836: Machinery for

roving, spinning and doubling cotton and other fabric substances.

(also Woodcroft)

12,384/1848: 21 December 1848: Running wheels and turntables; application

to shfts or axles driven by steam or other power.

(also Woodcroft who gives title as

Rail-way wheels and turn-tables)

767/1852. [packing ring for cylinders]

via Dickinson

309/1854: 9 February 1854: Hoist for raising and lowering railway

rolling stock and other articles.

408/1854: 21 February 1854: Welding.

322/1855: 12 February 1855: Construction of certain metallic

pistons.

451/1855: 1 March 1855: Steam-engines: obtaining motive power more

economically.

1299/1856: 7 June 1855: Safety valves, feeding apparatus for

steam-boilers.

1047/1857 Wrought iron rail chair

1527/1860: 23 June 1860: Supplying the tenders or tanks of locomotive

engines with water.

2460/1860: 10 October 1860: An improved mode of lubricating the pistons

and valves of steam-engines and other machines activated by steam.

White, John H. Some notes

on early railway lubrication Trans Newcomen Soc., 2004, 74,

293-307 states that there is an ealier British Patent

of 27 November 1858, but Peter Skellon's

Steam locomotive lubrication (p. 57) claims that there is no earlier

Patent. Displacement or hydrostatic lubricator.

924/1863: 13 April 1863: Machinery for hammering, rolling and shaping

metals.

48/1864: 7 January 1864: Improved machinery and apparatus to be employed

in, and improved modes of manufacturing hoops, rails and other articles of

cast steel.

3073/1864: 12 December 1864: Improvements in the manufacture of steel

and iron, and in the apparatus employed therein.

89/1865: 11 January 1865: Improvements in steam hammers and in appartus

employed in combination with steam hammers.

375/1865: 10 February 1865: Machinery for rolling and hammering iron

and other metals.

736/1865: 16 March 1865: Machinery for rolling and shaping metals.

1425/1865: 25 May 1865: Machinery employed in the manufacture of hoops

and tyres.

1975/1865: 31 July 1865: Improvements in the manufacture of hoops

and tyres and on the machinery employed therin.

342/1867: 7 February 1867 Machinery and apparatus for supporting,

moving and forging heavy masses of metal.

386/1867: 12 February 1867 Machinery for transferring engines, carriages

and waggons from one line of rails to another.

2956/1868: 26 September 1868: Apparatus for communicating between

the passengers, guard and engine driver of a railway train.

820/1869: 18 March 1869 An improved mode of ventilating railway tunnels

1060/1880: 11 March 1880: Working expansion valves of engines

John Goodfellow Ramsbottom

Born at Crewe in 1859, being a son of John Ramsbottom, President of

the Institution of Mechanical Engineers in 1870-71. He was educated at the

Manchester Grammar School and Owens College, and served an apprenticeship

with Beyer, Peacock and Co., Gorton. After filling various appointments at

the Works, he became Secretary of the Company until 1898, when he retired.

After that date he lived in London for a short time, and then went to the

United States, where he died on 26th August 1922.

Updated: 2014-10-06