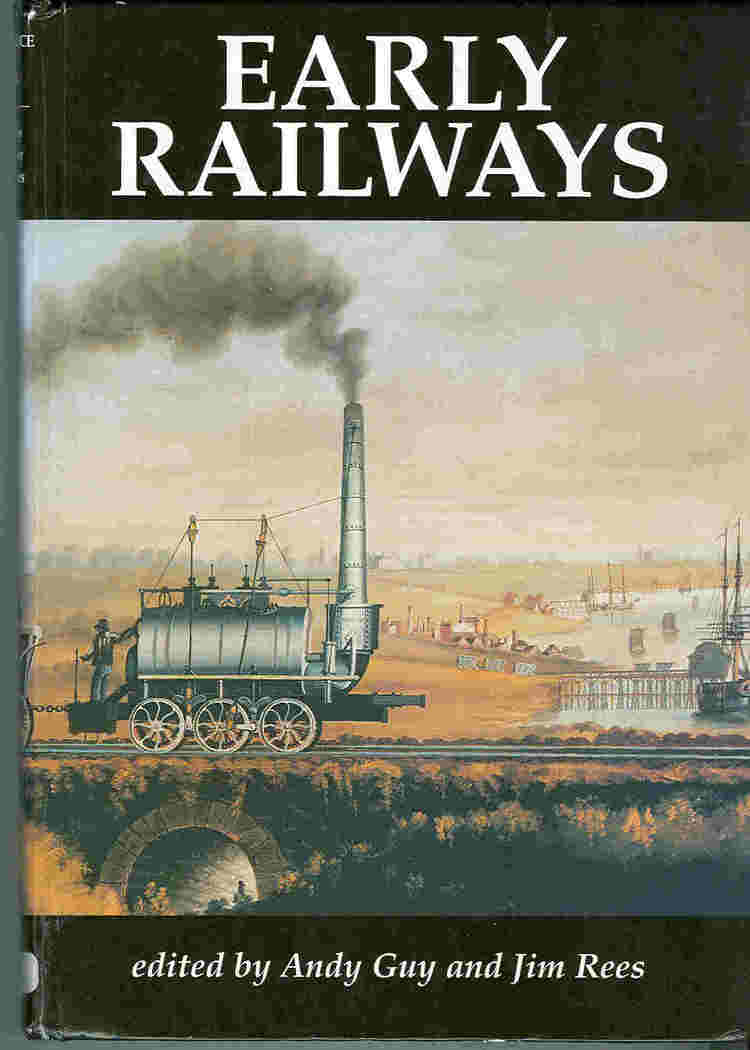

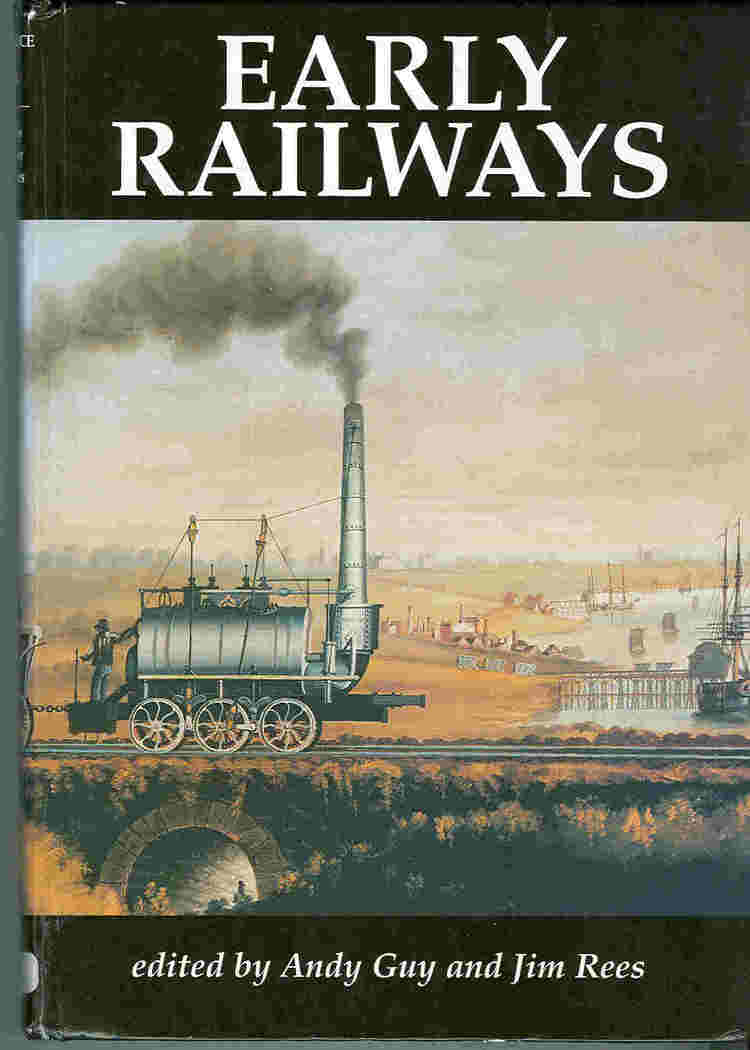

papers from the International Railway Conferences

Steam Elephant

| Early

railways: papers from the International Railway Conferences Steam Elephant |

|

These are without question the most important sources of information about early railways and early locomotives to emerge since Dendy Marshall, and in many cases change our perspectives of this period without diminishing the significance of George Stephenson. The involvement of the Beamish Open Air Museum and its staff has been highly significant. There have been four conferences so far, and the proceedings for three are available and have been examined. One paper from the first conference by Andy Guy introdues a paradigm shift and has been quoted at considerable length, albeit without the wealth of citations in the original. There is only one minor quibble about the proceedings: the cover illustrations on all three are highly significant and really deserved to have been reproducced in colour within the body of the work.

The first was reviewed by Michael

Rutherford in Backtrack, 2001, 15, 543.:

For your reviewer, not present at the Conference, it has been a long

wait for these papers - two and a half years but the wait has been worthwhile.

(Further conferences, Manchester this year and another in 2004, are planned).

Not all the papers read are included here but alternatilve references are

given for some of the others. The period covered is from the ancient world

up to a cut-off at 1840 and the geographical coverage (potentially) worldwide.

The range of subjects is good but the papers are something of a mixed bag,

many being of the type found in specialist railway and transport history

journals. Some would struggle even to find a place in the latter but the

best are absolutely superb and essential foundations for much inevitable

revisionism. In particular in this respect are the two papers prepared by

the editors; Andy Guy's work on huge quantities of primary

source papers held by the Tyne & Wear, Durham and Northumberland archive

in his "North Eastern Locomotive Pioneers 1805 to 1827: A Reassessment" and

Jim Rees' "The Strange Story of the Steam Elephant"

a once mysterious early six-wheeier, now so familiar it seems that a fullsize

working reproduction is under construction at Beamish – should at last

rescue the early history of the locomotive in the North East from the historical

treacle of Hedley-Stephenson (George)-Hackworth mythology. This is truly

new work where the epithet 'exciting' is not inflated rhetoric. Colin Mountford's

paper on rope haulage is a timely reminder of the longevity of the practice

insofar as incline operations are concerned but the crucial importance —

in the period dealt with — as an alternative to the locomotive for public

railways is sadly left out. The London & Blackwall Railway is not mentioned

and the 'reciprocating system' of Benjamin Thompson is mentioned but briefly

and nothing said of the details and schemes such as the Newcastle & Carlisle

and Liverpool & Manchester Railways.

The Conference was held at Durham University and inevitably there is a

concentration on topics in the North East and its claim to be 'cradle of

the railways'. Future conferences may temper that assertion!

The major irritant for this reviewer was the paper by Prof. Gamst, "The Transfer

of Pioneering British Railroad Technology to North America". Gamst not only

confuses 'technology transfer' and 'diffusion of technology', using them

interchangeably and even in the same sentence but leads us into paragraph

after paragraph of Socio-Cultural babble before resurrecting the Smilesean

version of George Stephenson and his invention of Rocket. What does it lead

us to? A chronology of the first 25 railways/railroads in the USA in the

sort of brief form collected on index cards or nowadays on a simple website.

None of this is explained in terms of the opening verbiage and comes as a

complete anti-climax.

It is a pity that the publication of the proceedings was left to the Newcomen

Society with apparently no assistance or commercial partnership. Although

the 'Keynote Address' (printed here with an unnecessary photograph) was by

Sir Neil Cossons, then Director of the Science Museum and in overall charge

of the National Railway Museum, there sadly appears to be little direct

contribution from that organisation and no groundbreaking papers from any

of its curatorial staff.

Your reviewer reckoned that nine of the papers were essential to him, seven

also very useful and the remainder padding. This is a good score and the

book is an essential reference and should be on everyone's bookshelf. Buy

it and wait patiently for the next one.

Early railways: a selection of papers from the First

International Railway Conferennce: edited by Andy Guy and Jim Rees.

London: Newcomen Society. 2001. 360 pp.

Cossons, Sir Neil. Keynote address, 1-6.

Begins with a quotation from Sir Arthur Elton who elegantly notes

the pivotal siginificance of the opening of the Liverpool & Manchester

Railway on 15 September 1830, and the involvement of George Stephenson in

that event. Also notes the significance of C.F. Dendy Marshall and Charles

E. Lee.

Lewis, M.J.T. Railways in the Greek and Roman world. 8-19.

Rutways, notably the Diolkos developed by Corinth to ship boats across

the Isthmus.

Karlsson, Lars Olov: A rediscovered early rail waggon 20-3.

A late 17rh century or eighteenth century mine wagon discovered in

Sweden.

van Laun, John. Pre-1840 trackways in south Wales. 27-45.

Gwyn, David. Transitional technology; the Nantlle railway. 46-62.

South Wales, in adopting and adapting the Shropshire philosophy of

cast iron plates on wooden rails, pioneered the all-iron edge rail. Its reign

here was relatively brief; but the plateway, although it undoubtedly came

to dominate the Heads of the Valleys scene, never acquired a monopoly. When

many of the Monmouthshire Canal Company lines changed to plateway the Trevil,

Rassa, Clydach and Blaenavon Railroads were not converted. For plateways

the ubiquitous stone block was favoured, with ear marks and a hole for the

fixing nail, particularly for the main lines built to Outram's specifications

by his younger cousin John Hodgkinson. Nevertheless, lapped coned plates

and eared plates closer to Curr's specification were used in the 1790s. Early

sills were of the horned variety and there appears no connection to Curr

here. From about 1807 (or possibly earlier) the dovetailed sill derived from

Curr's wooden sill was used exclusively up to (and beyond) 1840 by the ironworks

at Nantyglo and Rhymney for their quarry railways. Hodgkinson himself adopted

the dovetailed sill for the Sirhowy Tramroad branch to Rhymney and for the

Hereford Railway. Blaenavon converted to Outram-type plates about 1804, probably

to accommodate Clydach Ironworks who had a connecting line to Blaenavon by

then, but after 1818 it returned to sills. Tredegar stuck to a modified horned

sill until a wholesale change to chairs in the 1850s.

Hills, R.L. The railways of James Watt. 63-81.

Watt disliked locks as they limited capacity and favoured long level

routes with wagonways at the end to accommodate the change in height: such

canals were planned for Monkland, Strathmore and Campbeltown

Paxton, Roland. An engineering assessment of the Kilmarnock

& Troon railway (1807-46). 82-102

Wilmott, Mike: Early railways in Dorset; the industrial railway of

Purbeck, 103-13.

Middlebere Plateway which served the Norden clay pits. Involvement

of Benjamin Fayle. 3ft 6in gauge.

Guy, Andy. North eastern locomotive pioneers 1805

to 1827; a reassessment. 117-44.

A major review of locomotive engineers in Northumberland and Durham.

Contains many significant statements. Mentions Trevithick's Gateshead locomotive

constructed by John Whinfield under the control of John Steele: Steele returned

to London with Trevitick and was later killed in a boiler explosion on a

steam boat in France (p. 119). Considers that Christopher Blackett deserves

more credit than hhe is usually given (p. 120): he was one of the few to

show any inteest between Trevithick and Blenkinsopp. Notes that there

appears to be very little evidence for Blackett's adhesion trials at Wylam:

what little is in account book records. Similarly the 1813 locomotive constructed

by Waters of Gateshead (p. 120) is only traceable in the account books. The

second Wylam locomotive type (Puffing Billy) is much more visible and was

mentioned in a letter from Blackett to Hedley. (page 121). In 1814 there

was an important wayleave dispute which established that locomotives were

not a nuisance. Notes the doubling in the number of wheels to ease the stain

on the rails, but also notes the "thick fog of Hedley and Hackworth claims".

Matthias Dunn (121) "was a rising Tyneside colliery viewer.... His recently

redisccovered diary gives a professional and rerlatively unbiased summary

of the locomotive trials going on aroound him in 1815/16. He shows that three

locomotives were at work at Wylam by January 1816.

Remarkably, two of these engines survive, as Puffing Billy and Wylam

Dilly. Charlton suggested that they were totally new in 1828-30, and

not just rebuilt. The account entries are not at all clear, but there is

at least as much evidence within them that the .two engines were rearranged

and converted to four-wheelers, rather than replaced. A third engine, Lady

Mary, apparently survived to be photographed in the late 1850s or early

1860s, but the colliery valuations do clearly show that it had gone by the

early 1830s: an anomaly yet to be resolved.

It is recognised that the actual Wylam design was something of a dead end,

nor was there substantial development from its original form. It is noticeable

for example how little attention it received when locomotives were being

examined in the planning of the Liverpool & Manchester Railway. Its major

claim to fame was (and is) its remarkable longevity. All the more surprising

then to see, during wayleave renegotiations in 1829, the Colliery promising

'that the locomotive engines are to be discontinued' and that 'stationary

engines...will be substituted for the locomotive ones38'. A certain lack

of commitment is clear, although ultimately they were not removed for another

30 years. As at this same time it had converted half of the line to edge

rail, while the other half remained as plate — a situation that went

on for more than two years — a degree of indecision would seem to be

nearer the mark. The working arrangements must have been rather

interesting.

Kenton & Coxlodge (page 123)

It is generally considered that the first practical, everyday locomotive

was that built in 1812 for the Middleton Colliery near Leeds under John

Blenkinsop's Patent. Articles in the Tyneside press were followed that August,

just weeks after the opening, by a talk on the engine given by the Rev William

Turner to the influential Literary & Philosophical Society of Newcastle.

The subsequent introduction of the locomotives at the Kenton & Coxlodge

(K&C) Colliery just north of Newcastle is well recorded, but the spread

of information was more personal than just through the publicity. The owner

of Middleton Colliery, Charles Brandling, lived in Newcastle. The engine

builder, Matthew Murray was a Tynesider as was Blenkinsop, who took care

to keep tabs on developments in his home area.

He wrote to his friend, the K&C viewer John Watson, 'Chapman's Plan is

only a mechanical larceny — I will thank you for a description of it,

if you know his scheme', some six months before its first use at Heaton.

When it was about to start testing he commented, 'I don't think by the by

that either Chapman or Hedley will succeed in their mode of conveying goods'.

A year later, he was rather more concerned:

'I have been told that the Coxlodge Managers are going to adopt the Killingworth

Plan of conveying their Coals; shall I beg the favour of you informing me

whether their is any Truth in this information or not — I shall also

be obliged if you will inform me whether the Fawdon Owners intend to adopt

the Killingworth Plan or mine —Do you think the Killingworth Engine

will travel up hill or on a Level during Wet or Frost'.

That final question points to the advantages he considered his rack drive

held over the adhesion system, but particularly all these comments demonstrate

that Blenkinsop was clearly both aware of and concerned by the spate of trials

in the region.

As for the supposed loan of the first engine from Middleton to the K&C,

the accounts show that it was paid for in full, not lent, and state its name

Lord Wellington. The engine dimensions have been found, suggesting

the later K&C locomotives were altered from the Leeds design - adapted

for longer distances with harder work.

The first of the Tyneside engines was damaged very quickly, with Watson having

to request a new piston and set of gears. It was to be some time before they

were settled at work. As for the engines going out of use, there is an amount

of misunderstanding in the texts. In short, Watson claimed compensation from

his partner in the Colliery for their absence from 1815 to 1817, not because

they then returned to use, but because he was selling his share in the colliery,

and hence that was the extent of his alleged loss. And they were not just

put aside. Watson's Chancery case claimed that they had worked well, but

interference from another viewer had 'placed improper and ignorant men to

work the said engines, so that by their mismanagement the Engines have been

rendered unserviceable and laid entirely aside.' This seems to stem from

their work being concentrated on a bank that was at times 1 in 24. Even though

the design did not rely on wheel adhesion, that must have been a stern test

indeed.

The Colliery was sold to Brandling in 1817. He considered fully reinstating

the engines, but apparently decided to use them no more than from the pit

to the start of the bank, if at a1l. Blenkinsop's system had had a rather

inglorious outing in his home area, victim in part of an uncompleted line,

over ambitious loading and allegedly systematic abuse.

Heaton and Lambton

William Chapman of Tyneside was an unlikely candidate for Blenkinsop's accusation

of 'mechanical larceny'. As two major papers for the Newcomen Society (see

Forward's Chapman's locomotives vol.

28 page 1 and Skempton'

s William Chapman vol. 46 p. 45) have shown, he had a full and

distinguished career as a leading civil engineer, specialising in canal,

harbour and drainage schemes. He is regarded as the first to explain if not

invent the masonry skew bridge. Less well known was his deep involvement

in mechanical engineering, which led to the patenting of a successful rope-making

machine, the advocacy of the Boulton & Watt engine designand recognition

as an authority on the earliest steam boat engines.

Even more relevant were his colliery interests, ranging from the patent coal

drop to the preservation of mining records. No mere theorist, he sunk Wallsend

Colliery and had leases on Tyneside collieries, including the Kenton &

Coxlodge, for which he had built a major new iron waggonway in 1808. As early

as 1813, he proposed a Sheffield railway where 'long carriages, properly

constructed, and placed on two separate sets of wheels, 8 in all, may take

30 or 40 people with their articles to market' - a remarkably advanced concept

with a similar design proposed in 1825 for restaurant cars.

He had then a deeper mechanical, engine, colliery and railway experience

than has been credited. As already mentioned, he may have had an early Trevithick

locomotive, and probably inspired conversion of the Wylam engines to eight-

wheelers.

His patent of December 1812 covered bogies and a chain-haulage locomotive

system. The Butterley Company drawings for February 1813 give designs and

description for building such an engine. Known only as copies, doubts have

been cast on the document but the text has now been found in Chapman's own

hand for the same date.Completed that August for Heaton Colliery, the short

time scale suggests that the drawings must be similar to the engine as built,

hence a six-wheel, bogie, chain locomotive. The engine arrived in September,

was assembled by Butterley's fitter, Thomas Grice, and ready in October

1813.(page 124)

A supposed 'eye witness account' exists of the first trial, published by

R N Appleby-Miller. However, this has so many fundamental flaws that it must

be considered highly suspect. It is known that the engine was tested right

through 1814 and into 1815 until disastrous flooding closed the colliery

in that May. It finished life pumping and winding at the shaft, a particularly

easy conversion for a chain haulage locomotive.

There is some evidence that it was demonstrated on the Lambton waggonway

south of the Wear early in 1814. Approved by the Colliery Board that May,

they agreed to order an engine and to adapt for it the whole Lambton waggonway

system. In fact, the engine had already been designed. Built by Phineas Crowther,

it was ready and tested by the end of the year as an eight-wheel joint chain

and adhesion locomotive. However, the trials had to be extended as the new

iron waggonway was slow to complete, and were still continuing at the start

of 1816. It seems never to have done useful work, with the railway later

redesigned for self-acting inclines and stationary engines.

Newbottle (page 125)

If Chapman's engines are now considered rather eccentric, William Brunton's

'iron horse', propelled by steam-powered legs, is seen as famously mad. It

was realised some time ago that the design shown in the patent and subsequent

prints could not have worked. But work it certainly did — clearly it

is not known what the locomotive was like as built. Brunton himself described

it later as resembling a man pushing a weight forward, although the Patent

drawings suggest that it more nearly relates to a man with his back to the

boiler pushing with his legs.

The Butterley Company of Derbyshire — where Brunton was engineer —

made the first engine, for use in their Crich limeworks. The quarry was served

by a plateway some 1¼ miles long down to the Cromford Canal at Amber

Wharf, a gradient of up to 1 in 50 generally in favour of the loaded waggons,

and with a gauge of 3 feet 6 inches. Although Butterley owned the limeworks,

both it and its waggonway had been leased to operators, including Edward

Banks, the contractor for the Surrey Iron Railway.

The Butterley account book entry for the locomotive, often mentioned in the

texts, answers many of the questions on the engine when seen in the full

original. It states that it was built for Brunton personally, not, as has

been assumed, for the Company. The completion date is shown as March 1814,

although he had published details of it supposedly at work at Crich some

four months before, when he described it as having a single six-inch cylinder,

supplied by a wrought iron boiler of unusual construction, capable of a pressure

of 4-500 lbs/ sq inch, but normally working at 40-45 lbs (a comment that

will seem sadly relevant later) and it 'performs very well'.

Crucially, this engine was not then sent on to the Newbottle Colliery on

Wearside as state many of the texts. That was a second 'horse engine', purpose

built, constructed some six months later. Again debited personally to Brunton,

not to the Colliery, it cost £540 to Crich's £240. Brunton had

described his first machine as just two and a quarter tons, but later implied

Newbottle was nearer five, and it was probably twin-cylindered. It would

seem then to have been twice the price, twice the weight and twice the cylinders,

compared to Crich. It was finished in September and assembled at the Colliery

by Thomas Grice in October 1814.

The Newbottle waggonway was a major iron railway, built by the viewer Edward

Steel for colliery owner John Douthwaite Nesham and opened in 1812. For 10

years it would be the only line direct to the collier staithes at Sunderland,

so avoiding the expensive use of keels and the transhipment they involved.

However, at over 6 miles in length, with a difficult incline and costly

wayleaves, it was itself considered something of an extravagance.

The Butterley Company had already supplied machinery to the Colliery, but

it is likely that Brunton's approach was more direct. In a letter to his

brother in late April 1813, just before the patent, he spoke of 'going in

about a fortnight into the north'. Less than a month later, the Count de

Scepeaux wrote that 'the gentleman who hath taken out a Third patent to convey

coal waggons with a steam engine, hath been in this country. His engine instead

of drawing, push before it the waggons & I am told is not upon wheels.

Scepeaux was writing from Lambton, the neighbouring estate to Newbottle.

It seems quite possible then that Brunton may have personally interested

Nesham in his invention and persuaded him to either order or to test a

machine.

For Newbottle Colliery and John Douthwaite Nesham, 1815 was to be a year

of remarkable misfortune. The Wear keelmen, rightly judging the railway a

threat to their livelihood, rioted and burned down the Sunderland staithes.

A two months seamen's strike stopped all shipments of coal, the Colliery's

bank collapsed, and in June one of the pits was devastated in an explosion

that killed 57 miners. Finally, on July 31st, surrounded by a great crowd,

Brunton's engine blew up.

Contemporary accounts disagreed about whether the spectators had come to

see the first ever outing of the locomotive or that following a new boiler.

The Butterley entry confirms the boiler version, as did Brunton himself later.

This was the first major railway disaster, killing a dozen or more people,

and, with a humility unusual in engineers, the source of profound regret

to him for the rest of his life.

The joke design had a tragic punchline then. However, the explosion was due

not to an inherent flaw, but to the enthusiasm of the driver overloading

the boiler. And the assumption that the engine must have been quite useless

is not as clear cut as may be thought. As said, the detailed arrangement

remains unknown. The Crich machine was built and tested when Brunton was

the principal engineer of a leading firm. It was promising enough to build

another, much larger version some months later for Newbottle. It was later

described as working there with a load, up a gradient of 1 in 36, throughout

the winter of 1814 :(page 127). "It would seem that amongst contemporaries

Bruton's enging was given due attention" (p. 128).

Killingworth (page 128)

A note considers the veracity of the name My Lord for George Stephenson's

first locomotive. Guy considers that this locomotive was "quite successful".

and the cost of moving coal was halved. Notes the importance of the patent

taken out with the colliery viewer Ralph Dodds. The Killingworth owners were

pleased and paid the patent expences and paid Stephenson a bonus. Notes how

Stephenson was "a very well regarded man in a field of experts". Matthias

Dunn singled him out as the only unqualified success of the many locomotive

pioneers of 1815: " George Stephenson has completely succeeded in gatting

two travelling enginnes into complete work which save about 8 horses each.

Eighteen fifteen was a seminal year. It saw engines at Wylam, Killingworth,

Kenton & Coxlodge, Heaton, Lambton, Newbottle and later at Wallsend.

By the end of that year, of these seven sites, only at Wylam and Killingworth

had it become established. This was due as much to misfortune as to failure.

The Blenkinsops had been abused and broken, Heaton colliery laid off due

to flooding, Newbottle had suffered an overloaded boiler, the track at Wallsend

proved unsuitable. So ended, with very mixed fortunes, the first experimental

period in the North East.

George Stephenson (page 129)

Traditionally, the era of Stephenson followed. The main texts agree that

there was no other figure continuing locomotive development in the north

east, if not the country, for the next decade (cites Dendy Marshall).

From 1815 his reputation grew apace, bolstered by his 1816 patent and the

general working success of the Killingworth engines. Repeatedly developed,

improved and quantified by Stephenson and Nicholas Wood, they became the

Tyneside engines that informed and influential visitors wished to see. By

1820, he is considered as a consulting authority on railways in the region

and beyond, surveying a number of lines. At this stage he was not locomotive

fixated — they are recommended for straight and level lines with heavy

traffic otherwise he suggests inclined planes, stationary engines and/or

horses

In 1813, when manager of the Vane Tempest group of collieries, Arthur Mowbray

had unsuccessfully promoted plans for a railway from the Rainton pits to

Sunderland. As seen, he tried again in 1815, suggesting a line on the

Newbottle/Brunton scheme. Edward Steel's proposals included estimates that

strongly imply the use of locomotives. They were rejected. In 1819 he employed

George Stephenson, 'a Man of great reputation and much experience in the

making of Rail Roads, and particularly in the use of Machinery', to survey

a line. The plans, which did not include locomotives, were again turned down.

Stephenson then made a remarkably bold offer. He would supply the machinery,

run the railway for a year at the old rates and then hand the line back for

no payment, on the basis that the savings would exceed his entire costs in

that time. However, the new controller of the colliery, Lord Stewart (later

Marquess of Londonderry) had taken violently against Mowbray. Within weeks

he had been replaced by John BuddIe and all his proposals put aside. (page

130)

The irrepressible Mowbray quickly renewed his interest in the proposed Hetton

Colliery nearby. With his previous connection with Stephenson, the scene

is now set for this famous railway over the hills to Sunderland. Again however

the story is considerably less straightforward than the texts suggest. As

early as September 1819 Stephenson submitted estimates for the railway —

they do not include locomotives. Other estimates were made that year for

joining the new Colliery to the Newbottle line but using horses and inclined

planes. In July 1820 Edward Steel was noticed surveying the line to Sunderland

and three months later Benjamin Thompson was claiming that he had been approached

to build and run the railway on contract, presumably on his reciprocating

system.

Mowbray finally returned to George Stephenson, who worked with his brother

Robert on all the colliery and waggonway engines. But it has been seen that

this, supposedly the first railway built for purely mechanical haulage, could

well have taken a quite different route, could well have been constructed

instead by Steel or Thompson. Even Stephenson had initially considered using

horses rather than locomotives on the two short sections for which they were

suited. And Robert, the resident engineer, was sacked by the owners after

little more than a year, in acrimonious circumstances. On one of the

locomotive-hauled sections they were never very satisfactory, being replaced

by stationary engines in mid-1827 and only barely surviving on the remaining

section.

Hetton's initial success considerably enhanced George's reputation. Killingworth

led on to the national platform that was the Stockton & Darlington Railway.

Exactly how locomotives were decided upon there has always been anecdotal.

But that, and an account of the deliberate marketing of George Stephenson,

is contained in an important archive at Durham — the Hodgkin letters.

All are from Edward Pease in Darlington to his cousin Thomas Richardson,

the London banker. The following extract comes from a letter dated 10 October

1821.(page 131)

'Dear Cousin,

......... the more we see of Stephenson, the more we are pleased with him,

he commences the setting out of the line in a few days — he is altogether

a self taught genius, a man thee would be remarkably pleased with, there

is such a scale of sound ability without anything assuming, Cousin Jonathan

[Backhouse], Joseph & myself went to see his works about 5 miles from

N Castle, & were exceedingly pleased with the correctness of every thing

he had designed and executed — don't be surprised if I should tell thee,

there seems to us after careful examination no difficulty of laying a rail

road from London & to Edinburgh on which waggons would travel & take

the mail at the rate of 20 miles per hour, when this is accomplished Steam

vessels may be laid aside! — we went along a road upon one these Engines

conveying about 50 tons at the rate of 7 or 8 miles per hour, & if the

same power had been applied to speed which was applied to drag the waggons

we should have gone 50 mile per hour — previous to seeing this Loco

motive Engine I was at a loss to conceive how the Engine could draw such

a weight, without either having a rack with teeth laid in the Ground &

wheels with teeth to work into the same, or something like legs — but

in this Engine there is no such thing, the way and wheels are exactly same

as a common Rail way & by the Cranks of the Engine first propelling the

fore wheels of the waggon & then the hind wheels the loaded waggons are

impelled forward from all this judicious man says & all we can yet see,

no doubt has yet entered my mind but we shall make a good thing of this

concern.'

This must surely be one of the most important railway letters. If ever a

clear explanation was wanted why locomotives were adopted for the S&DR,

it is here. The extraordinary, almost boyish, enthusiasm of this supposedly

dour and practical Quaker businessman, the grasp of the possibilities, the

complete faith given to Stephenson are all here. And it is addressed to

Richardson, the money man who will partner Pease in the railway through its

troubles, who will back both Robert Stephenson & Co and George Stephenson

& Son.

The letters of 1824 and 1825 that follow give a major insight in the making

of George Stephenson. Pease and Richardson determine to market the man in

the most modern way — they were his spin doctors then as much as Smiles

would be later. They cover everything from his scale of fees to the essential

need for fresh patents, from the advantages of a new address to his actual

dress:

'he is a clever man, but he must have leading straight'; 'he should always be a gentleman in his dress, his clothes real and new, and of the best quality, all his personal linen clean every day his hat and upper coat conspicuously good, without dandyism'.

Increasingly, inevitably, they also reflect the frustrations of his

absence from the engine works and from their railway. The control they hoped

for slips away as the success they promoted takes him on elsewhere - to his

great railway incontinence of the later 1820s and beyond.

John Buddle (page 132)

The conventional story of this pioneering work in the north east to 1815

— and it was happening virtually nowhere else — is capable then

of some modification, as are elements of the early career of Stephenson.

However, to approach that initial problem of the rogue engines entails the

reappearance of a forgotten character.

The driving force of the colliery was the viewer — part manager —

part mechanical engineer, mining engineer, surveyor — responsible both

for the pit and the waggonway arrangements. In the north east in our period,

there was a viewer so dominant that in his own lifetime he was known as the

'King of the Coal Trade'. Renowned as one of the first so-called' scientific

viewers' he was the major instigator of new techniques in the industry, including

segmental iron tubbing, district working and pillar robbing. He promoted

the experiments of Davy into the safety lamp and was the first viewer to

order it. In addition, he was a great believer in mechanisation in general,

introducing underground engines, the first Tyne steam boat, and tub transport

— a form of containerisation new to the region. His name was John Buddle.

If that name is not familiar, then it is hardly surprising. The locomotive

texts give him no more than a passing mention at best. So, by the early years

of the 19th Century this inventive colliery viewer, this promoter of

mechanisation, an authority on waggonways, has apparently no significant

role in the remarkable flush of experiments taking place on his patch. This

appears inconsistent and unlikely.

According to Ottley (who does not make a claim KPJ and it be entry 242),

the first publication dedicated to steam locomotives was an 1813 pamphlet

by the Chapman brothers describing their patent chain engine. Enquiries were

directed to themselves and to John BuddIe. In fact, his account books show

that BuddIe paid for that patent. When the engine was tried at Heaton, it

was BuddIe who designed the necessary railside kettle. He prepared the chains

for the track, he paid for fitting up the engine, he paid a share of its

purchase price, he conducted its trials and oversaw its modifications.

He was a partner in and the viewer of Heaton. He was also the viewer for

the Lambton Colliery Board' and within days of discussing a new engine design

with Chapman, he has their agreement to ordering a locomotive and to the

waggonway rebuilding necessary. The Board pays for the engine, but via BuddIe

personally and again he conducts its trials

So, he is very intimately concerned with these two Chapman engines —

in the patent, in the waggonways they need, in the collieries they serve,

in their trials and in their cost. It may be more realistic to see these

as Chapman-BuddIe locomotives. But this remains within the known engines.

One of the potential rogue locomotives mentioned in the Introduction comes

from an account book held at Beamish. This gives a kit of mechanical parts

made by Hawks of Gateshead for an unnamed colliery from late 1814 to early

1815 — a six-wheeler, and so does not fit any of the available early

engines. The internal evidence in this book shows clearly that this locomotive

was built for Wallsend Colliery. The manager and viewer was John BuddIe.

The existence of this important new locomotive is confirmed by the invaluable

Matthias Dunn, who stated that 'Wallsend have also started a Travelling Engine,

but the wood ways obstruct it much'. In May 1816, he noted that it had been

removed to the sister colliery at Washington - another BuddIe pit and another

previously unrecorded location — but that it 'cannot be made to answer

any good purpose, and is for the present set by'. (page 133)

It would seem that it was subsequently not only reinstated, but may have

been joined by another. The well known complaint in 1821 from Losh to Pease

about Stephenson's choice of malleable rails stated, 'At Wallsend they have

long employed the Travellers...', but, with no known engine there, that clear

statement has been understood to mean the neighbouring slaithes at Willington

for the Killingworth line. There is now however sufficient evidence from

the colliery accounts, the Dunn diary and the Losh letter to establish this

new locomotive, introduce Hawks & Co as a builder, and to locate it at

Wallsend and Washington.

Another has long been suspected as working at Whitehaven. Dendy Marshall

suggested that it may have been built by Taylor Swainson, but in 1978, Peter

Mulholland clearly showed (The first railway locomotive in Whitehaven, J.

Cumberland Rlys Ass, 1978) that the locomotive had been ordered by the

resident viewer, John Peile, under the supervision of BuddIe as consultant

for the colliery. It was constructed by Phineas Crowther of Newcastle, to

the designs of William Chapman. A somewhat confused mention of it at work

has also recently been found,

'Several carts being loaded and linked together in a long line, a machine of iron, called, from the office it performs, and also from its shape, a horse, is fastened before the first. This horse contains a steam engine inside, which causes the wheels on which it is raised to run in a toothed groove below, and thus to drag along the rest of the waggons to the place where they are to lay down their burden. This is one of the wonders of modern invention..

Most importantly, the drawings survive, both for the construction

in 1816 and its conversion to a stationary engine two years later, so that,

for the first time, a clear view can be given of a Chapman engine as built.

See Jim Rees below

L.G. Charlton The Steam Elephant J. Stephenson Loco. Soc., 1980, p.

330 noted a further Chapman-BuddIe engine. In 1820, BuddIe bought back the

Lambton locomotive to use on a new line he was constructing at Heaton. After

some trials on the old route, he found the major fault to be lack of steam

capability, and so completely rebuilt the engine. The boiler was lengthened

fully three feet and fitted with a single tube, the eight-wheel double chassis

reduced to a single frame four-wheeler, and he connected the wheels with

an endless chain. This 'Heaton II' is nearer a new engine than just minor

adaptations, and the redesign was John BuddIe's. It must be the long-queried

'large travelling Engine' at Heaton mentioned by Losh in 1821, who says that

they have now put springs to it and so suggests that it is BuddIe who first

fitted a locomotive with solid springing. John Birkenshaw confirmed the existence

of the engine in an open letter to Chapman in 1824 .

In 1819 BuddIe gave up many of his other colliery interests to become viewer,

and later manager, of the important Londonderry collieries based at Rainton

and Penshaw in Durham. Their account books show that' a travelling Engine

for leading Coals' was built for them by Joseph Smith, payments on account

being made in early and late 1822. Smith, a previously umecorded maker, was

engine wright at Heaton, and so had already rebuilt that engine for BuddIe.

He would shortly go on to succeed the sacked Robert Stephenson as engineer

at Hetton.

This engine would have mixed fortunes. It was included in the estimates for

the planned Seaham railway in 1823, but construction was postponed. Thomas

Wood of Hetton, in the L&MR Parliamentary hearings of 1825, said that

it had been laid aside and BuddIe would appear to have made a similar comment

that same year. In 1826 it underwent trials near Rainton, but broke the rails

and suffered Slip - it was apparently purely an adhesion engine. The following

year, it must have been this locomotive that was shown to the Duke of Wellington

by Lord Londonderry and BuddIe on the Rainton line. The Smith engine would

seem then to tie up a number of long standing questions.(page 134)

Even less detail is known of what may have been the first locomotive crane.

In 1822, Londonderry was committed to the building of an extravagant country

house at Wynyard, north of Stockton. BuddIe made the arrangements for getting

the very large amounts of stone to the site, by ship and then cart. Once

there, he used a temporary railway and some form of locomotive fitted with

a crane. It seems that neither was used much, if at all, and the railway

was sent back to Rainton early in 1825.

This use matches the machinery specified for the building of Londonderry's

new harbour at Seaham, of which Chapman was engineer and BuddIe the manager.

For the construction work itself, Chapman proposed both a travelling crane

and a locomotive engine with a winding apparatus. It might be imagined that

this was perhaps an adaptation of his Lambton design, which used both adhesion

and chain haulage. When harbour construction started in 1828, that engine

was in use, lifting rock from the shore and transferring it along the site.

BuddIe wrote proudly to Londonderry, that it had taken its station and how

it 'gives an appearance of civilisation to the place. Nothing I think gives

such a finish to a Scene of this sort as to see an engine smoking upon it'.

Shortly after, there is a reference to using 'one of our locomotive engines

to keep the basin workably dry'

Now it may well be that the Wynyard and Seaham engines are the same —

there is certainly the same purpose to them. Clearly however, the belief

that it was Stephenson alone who continued the development of the locomotive

is misplaced. BuddIe and Chapman continued it in 1815 with the

Wallsend/Washington engine, in 1816 with Whitehaven, 1820 with the rebuilt

Heaton II, 1822 with Rainton, followed by the dual-purpose Wynyard/Seaham

locomotive cranes.

Buddle, Chapman & Stephenson (page 136)

Despite this, it remains hard to deny the dominant role of George Stephenson.

It is his promising first engine that founds a dynasty of locomotives, it

is his design of 1815 that will be the most successful arrangement of locomotives

for the next decade, that will be lead on to Hetton, the Stockton &

Darlington, will allow him the platform to press for locomotives on the Liverpool

& Manchester. A formidable pedigree.

Even here, however, there is some evidence for reconsidering the story. No

one has pretended that the first Stephenson engine in 1814, the geared My

Lord, was hugely original. Rather, it was a synthesis of locomotives

he had had the chance to examine, especially the Blenkinsop of the Kenton

& Coxlodge. Such a pragmatic approach was sensible and effective, but

this practical solution may not have been his alone.

There is an unpublished collection of letters at Durham that may be significant,

in which Doctor Joseph Hamel writes to John Buddle. Hamel is the agent, the

information gatherer, for Emperor Alexander of Russia. In the first letter,

he refers to a visit he made to Newcastle which is known from another source

to be in early November 1814 — the time of My Lord and some months

before the 1815 patent engine. He asks for a model of Stephenson's locomotive

and some exact drawings. Does Mr BuddIe object to this request? Will Mr Chapman

assist or give his consent?

This seems a remarkable situation. Why should BuddIe or Chapman have such

control over the design of Stephenson's first engine, and in particular why

is their permission necessary? Stephenson works for neither of them, nor

are they associated with him. One interpretation is that they have given

some direct assistance to the inexperienced Stephenson in his first design,

the drawings for which BuddIe is later able to send on to Hamel. They may

be in the Russian archives yet.

That leaves the seminal 1815 patent that followed, the essential Killingworth

and Hetton design that made his reputation, and which everyone came to see.

Charlton's Locomotive engineers noted a remarkable entry in Nicholas

Wood's private view diary which stated that a locomotive of the' same

construction' as the patent engine had been tried before that patent was

dated, and so had made it null and void. It had been run by Nowell &

Co of Sunderland and by Grimshaw of Fatfield Colliery, and tried on Nesham's

Newbottle railway. Such a statement made by Stephenson's closest collaborator,

must carry weight.

Charlton got little further than this. In fact, John Grimshaw was an experienced

engineer who would later play a significant part in persuading the businessmen

of Stockton and Darlington to opt for a railway rather than canal. 'Nowell'

is a misreading for William Norvell — a millwright, later to adapt a

famous rope-making patent of Grimshaw's. The real question is, what engine

or design could have been of the' same construction' as Stephenson's?

In essence, if the similarity was based on the patent claim to an endless

chain connecting the wheels, then there is certainly a design that predates

it. Chapman's pamphlet was the first publication dedicated to steam locomotives.

The second was an anonymous proposal for a train of locomotive and waggons

with all the wheels driven. The coupling was by endless chain :

'rotatory motion to be communicated to the wheels by means of an endless chain which passes over toothed and grooved pulleys fixed on some convenient part of the axles of the wheels.. . Respecting the chain...it is composed of circular and oval links, placed alternately, and may easily be repaired or lengthened by means of shackles with screw-bolts, etc. We conceive it to be of new and advantageous construction, and calculated for general use in mechanism [sic].'

The pamphlet was a reprint of a letter to the Royal Society of Arts

written by two Scarborough men, William Tindall and John Bottomley, and dated

4 June 1814. That is to say, not only eight months before Stephenson's Patent,

but even before his first, the geared engine, had drawn breath. Stephenson's

preference in his improved design had been for a crank to couple the wheels,

and only when that had proved impractical had an endless chain been substituted.

It would seem that he might have borrowed the idea.

The Scarborough connection initially appears unpromising. The area had no

waggonways, and so the inspiration for the design and its translation to

the Wear seems unlikely. But there is a common link, and that is William

Chapman.

As suggested before, Chapman may well have worked with Stephenson in 1814.

During that year, he was also down at Scarborough, where he was the engineer

for the new harbour works. It was the area that his wife came from, and he

had encouraged his contacts there to invest with him in the Kenton &

Coxlodge colliery some years before. A major partner with him and its banker

was James Tindall of Scarborough — uncle to both William Tindall and

John Bottomley.

In short, it is suggested that the Newbottle engine may have stemmed from

the Scarborough proposal, hence its chain connection nullified the Stephenson

patent. The original idea probably came from Chapman, the great chain man

and the link between them all. When reporting in 1824 on what would become

the Newcastle & Carlisle Railway, Chapman suggested a design of train

in which adhesion could be increased without additional weight if one or

more of the carriages were to be coupled to the locomotive drive.

This evidence is essentially circumstantial, but there is a case to be made,

for there can be no doubt that Nicholas Wood knew of a built design that

had ruined a patent seen as the embodiment of Stephenson's Killingworth and

Hetton engines.

Conclusion (page 138)

It is quite possible then to review this period with the aid of significant

new sources. Most have been found in the County Record Offices, principally

of Durham and Northumberland, but document extracts familiar from the texts

have yielded a surprising amount of fresh information when seen in the full

original. There can be little doubt that further valuable material remains

to be unearthed, and will reconfigure this apparently well-known history.

In general terms, a significant but seldom stated facet of the domination

of the region in the development of the locomotive is its remarkably small

area. Before 1825, all the north eastern waggonways discussed were within

a diameter of just 15 miles. Even on foot, any interested party in 1815 could

have seen the engines at Coxlodge, Heaton, Wallsend and Killingworth in less

than an hour. These trials then were on local, familiar ground and in the

open air, not distant, remote or secret. The choices that Arthur Mowbray

had at his fingertips for Rainton and Hetton are a case in point.

It has been seen how intertwined were some of the relationships between the

pioneers, and how aware they were of each other's progress. For the viewers

this was emphasised by the nature of their profession — as resident,

group, consultant or check viewers they were constantly involved with the

affairs of collieries other than their own and regularly came together at

the meetings of the Coal Trade. Rather than happening in isolation, the progress

of the various tests must have been common knowledge and the subject of detailed

discussion between them.

More specifically, it has been possible to add information to the well known

trials at Gateshead, Wylam, Kenton & Coxlodge, Heaton, Lambton, Newbottle

and Killingworth. As for the 'mystery' engines, new evidence can be offered

for the identification of the locomotive seen by the Duke of Wellington,

the Stephenson patent breaker, the Wallsend and Rainton engines.

The early career of George Stephenson can be reconsidered — the first

engine, the first patent, the enchantment of Edward Pease, the conscious

marketing of the man. Nicholas Wood played his part in selling the Stephenson

story as well. His 'Treatise' conceals his own knowledge of the nullification

of the Patent, fails to mention the experiments by others after 1815 or the

dreadful Newbottle explosion that year. Prior to publication, Longridge warned

Pease that 'Wood's Book must undergo a strict censorship before it is published

and I fear this will be a work of considerable delicacy, but it must be done.'

A fortnight later, Wood wrote placatingly to Edward Pease that the book would

be worthwhile and necessary 'if it only be done judiciously and without injuring

my friends', in particular George Stephenson. When so many later histories

of these experimental years were understandably based on his expert, contemporary

account, it is unfortunate that it is at best incomplete and at worse quite

knowingly misleading.

Finally, it can be suggested that John BuddIe be given due recognition. He

is intimately concerned with Heaton and Lambton. He is responsible for the

locomotives used at Wallsend and Washington, Whitehaven, Heaton II, Rainton,

Wynyard and Seaham; he places Hawks and Joseph Smith in the list of engine

builders. And it is not just the totals of BuddIe and Chapman which are

impressive, it is the sheer variety. They are built with four wheels, or

six, or eight; connected by gears, connected by chain; bogie frames, single

frames; adhesion, chain, and both together; first use of solid springs, first

locomotive crane. Such a richness of thought, such open-minded pragmatism

is hard to match in the contemporary pioneers. BuddIe's contribution has

long been unknown and Chapman's underestimated. Both richly deserve

reassessment.

Rees, Jim: The strange story of the Steam

Elephant. 145-70.

The papers at this conference in general and that by Andy Guy in

particular, are striking confirmation that, with honourable exceptions such

as Dendy Marshall and Charlton, the history of locomotives as it has evolved

from the informed but selective Nicholas Wood onwards is in need of continued

study and reanalyses of participation, innovation and influence. This paper

sets out it is now quite clear that the locomotive now known as the Steam

Elephant is the locomotive of 1815 built at Wallsend by John BuddIe and

William Chapman, for use on its colliery waggonway, the machined metalwork

being supplied by Hawks of Gateshead. After a shaky start the locomotive

had a working life longer than many of the other early engines. It was fitted

with slide valves rather than plug cocks. The main initial sources were (1)

a vignette on a map recorded by R.N. Appleby-Miller in The Engineer

(18 September 1931) and subsequently in J. Stephenson Loco Soc. (1942):

tis was suffiocient for Forward's

Chapman's locomotives vol. 28 page 1 ; (2) a water-colour painting

discovered and exhibited in 1965 and (3) an oil-painting acquired by Beamish

in 1995. The last is very important and clearly identifies the location as

Wallsend, incorporates Carville Hall and probably Chapman''s skew arch. Rees

also indicates that the painting appears to contradict Jack Simmons' assertion

that there were no early paintings. Notes the significance of Peter Mulholland's

research (The first locomotive in Whitehaven, Ind. Rly Rec., 1978

(75)) which showed the involvemnt of Phineas Crowther for John Peile, the

Earl of Lonsdale's viewer in 1814. This was not successful and by 1818 was

beinng used as a stationary engine at a quarry. Another notable source is

the Wallsend. Account Book which includes "six waggon wheels for a locomotive

engine".

On 3 November 1821 William Losh wrote to Edawrd Pease telling him where he

could see locomotives performing on his patent rail in addition to

Killingworth:

'At Wallsend thet have long employed the Travellers and one of them the enormous weight of nearly nine tons and without springs or pistons [meaning steam springs], and yet the Patent Rails of the above weight stand without an instance of breakage, altho' the engine goes with a velocity of at least 7 miles an hour very frequently down a Plane.'

The letter is of immense importance and the use of a selective quote

from it by Dendy Marsha1l which is then dismissed as 'by which he means

Killingworth', shows that Marshall cannot have seen the complete original

letter, for this interpretation negates the very point it is making. Losh

was a local man and when he said 'Wallsend,' he meant it.

The Dunn Viewbook, 'Wallsend...have started a Travelling

Engine.'

In 1997 Beamish acquired the view book of Matthias Dunn for the years 1815-2464.

As well as being of immense importance in the field of mining history, the

book contains an astonishing summary of locomotive working in the north east

for the year 1815. In it he states, 'Wallsend...have started a Travelling

Engine, but the wood ways obstruct it much,' and on 17 May 1816 'The Travelling

Engine removed from Wallsend to Washington cannot be made to answer any good

purpose, and is for the present set by.' Perfect confirmation of the account

book date and location and when taken with the reappraisal of the Losh letter,

suggests that the engine returned to Wallsend and useful work, following

conversion of the way to Losh's iron rails, in order to have been 'long employed'

by 1821.

The issue of locomotive working on wooden rails is neither rare nor surprising,

yet has become presumed to a be problem, or impossible65. The logging railways

of late 19th Century America and Canada should be sufficient to dismiss the

thoughtless belief that wooden rails cannot support a locomotive66. By 'wooden

rails' I am referring to the simplest 4 by 4 inch hardwood rails as revealed

by the Lambton 'D' Pit excavation of 1998 rather than iron-topped wood rail.

As late as 1819 Stephenson accepts their use for the Garesfield and Pontop,

where he says

'N.B. Between Winlaton Mill and the staithes, the Road is composed of Wood two thirds of the Way; but as the locomotive Engine need only travel with 8 waggons at a time, this it can do, notwithstanding the friction arising from the wood rails. Iron can be substituted as opportunities offer, or, as the wood fails68.'

Certainly on anything other than a straight line, running any length

of train on a curve on wooden rail would soon grind to a halt through excessive

friction. It is more likely, however, that the problem with wooden rails

was that, when wet, they could rapidly prove impossible on any sort of incline.

One can easily imagine the thundering wheelslip of the Steam Elephant on

the short and vicious Wallsend plane with a full load of empties on a wet

day.

A letter from Chapman to BuddIe on 16 May 1814, regarding the first Heaton

engine throws some contemporary light on the issue' ...although the Way does

not complain, yet 3 wheels carrying nearly all of the Weight destined for

four...Must indent or depress the Fibres of the Wood and create an artificial

hil1...' (a nice pre-Whyte description of an 0-6-0 versus an 0-8-0).

It is worth remembering also that the use of wooden rail would to some extent

have mitigated the worst effects, on engine and track, of running completely

unsprung locomotives with cast iron wheels.

Dunn's account of the movement of the locomotive to Washington for trials

at the owners colliery there, is something which is otherwise entirely

unrecorded. Clearly the engine was no more successful there than it had been

at Wallsend, but some aspect of the operation at Washington must have appeared

more favourable to the locomotive, possibly iron rails or easier gradients,

for the move to be considered. Washington shipped coals from both the Tyne

and the Wear. If running the four miles to the Tyne, both rail and gradient

may have been acceptable, but the distance simply unreasonable for the steaming

capacity of the boiler. Whatever the facts may have been the engine was obviously

not long in returning to Wallsend.

The Hetton Tentale Account;

1834.

Just when it appeared that the 'mystery of the Steam Elephant' had been tidily

solved and independently confirmed from contemporary sources, came the discovery

of a further illustration of the locomotive, from a most unexpected time

and place. A volume of tentale accounts for the Hetton Lyons, Elemore and

Eppleton group of collieries in Durham for the year 1834, showing a fine

illustration of the locomotive, apparently in an updated and rebuilt state,

on the title page . The volume revealed no other recognisable reference to

the locomotive.

What could a BuddIe and Chapman Wallsend locomotive of 1815 be doing, nearly

20 years old, on a Stephenson line, the early locomotive history of which

is apparently well known? The Hetton illustration is a fascinating codicil

to the story of the Wallsend Elephant. It could be, of course, that the engine

is simply being used in an iconlike manner, not simply as our engine, but

as the engine. Examination of the possibilities, however, may lead us into

tackling some Hetton mysteries and misconceptions too.

A close look at the illustration appears to show the engine rebuilt with

a much longer boiler (as Buddle did with the Heaton II locomotive)?!, at

the same time bringing the cylinders from over the crankshafts to the front

and rear driving wheels and converting it to direct drive to crankpins mounted

on the wheels; the gears are simply retained for their coupling function.

As previously discussed, the engine as built may be estimated at some 7½

tons weight, with a top speed of 4½ - 5 miles an hour; in the condition

illustrated here, the locomotive is much more in line with Losh's figures

of 9 tons and seven miles per hour, giving the possibility that the rebuild

took place while still at Wallsend, possibly even on return from Washington.

In general terms the rebuild would have given much higher speed, much greater

steaming capacity, but reduced haulage capacity and incline climbing capabilities

(although sufficient with iron rails?). There are enough otherwise insignificant

details, such as the plating lines on the feedwater heater to confirm that

this is the same engine and not just the same ~ of engine, and enough differences

to suggest that it has not been simply copied from some older illustration.

However, a closer consideration of the Losh letter reveals an odd implication,

'At Wallsend they have long employed the Travellers and one of them the enormous

weight of nearly nine tons'(my underlining). Implying at least two Elephants,

if not a herd; one or both with the noted modifications.

Wallsend and Hetton were held by different coal owners between whom there

was often the most intense rivalry, and the movement of equipment from one

to the other not just a matter of need on one side and surplus on the other,

but a more notable and unusual step.

Firstly then a look at the earliest motive power situation at Hetton and

perhaps the suggestion that we may not know what we thought we knew. The

common knowledge that Hetton opened with five of Mr Stephenson's fourwheeled

patent engines seems to be everyone simply repeating Sykes and Richardson,

who are in turn repeating newspaper accounts, yet a valuation in 1823 by

none other than Nicholas Wood lists only four locomotives. The Hetton coal

bill mentioned earlier shows an apparent Stephenson six-wheeler above the

words 'The Locomotive Steam Engine which draws 100 Tons Weight of Coals from

Hetton Colliery'. It may be worth observing that this would be highly unlikely

unless the engine were geared, however it is probably best dismissed as boastful

exaggeration as the same wording appears under another bill from the 1820s

under a four-wheeler!

Certainly in October 1821 in a letter to William James, Stephenson said that

he was about to start building three locomotives for a local colliery (Hetton,

which opened just 13 months later), and therefore could not make one for

James. Comparison with sources such as the Watson papers for Murray or Robert

Stephenson & Co's later problems producing Locomotion on time for the

Stockton and Darlington, would suggest that Stephenson would have been doing

very well to produce three in the time available! Perhaps he did build three

as he said and the line then acquired first one, then another, secondhand.

There is no doubt that by the time of an 1827 valuation there were five engmes.

It is sometimes considered that in this era before the standardisation of

gauges, the movement of locomotives between one railway and another would

have caused considerable difficulties. Some consideration of the mechanical

work however, shows that regauging an in-line cylindered engine has by no

means the massive implications that are created with a more modern 'conventional'

framed steam locomotive, but simply requires the lengthening of beams and

axles.

There is no doubt that there are odd references which repeatedly divide the

Hetton engines into groups of three and two. Rastrick in 1829 talks of the

three he saw in 1825 having moved - they are supposed to be identical. Three

are named, as were other Killingworth engines, after racehorses, as Dart,

Tallyho and Star. An 1831 valuation gives two spare and at a lower

value than the three at work.

The period between the withdrawal of the first engines at Hetton and the

introduction of the first bought-in engine in 1857 needs further study and

clarification. The two engines built in the colliery workshops in the early

1850s have considerably obscured and confused our view of the 'Stephenson'

engines. Roger Lawson, who worked on the line from the 1850s, spoke in June

1908 of one of the 'old' engines being called the old Fox. One wonders

at its relationship with Tallyho. A nick-name for the same, or a working

partner? His account is confused and self contradictory, but one of the only

insights we have. He appears to be saying that one of the' old' engines as

well as one of the home-made ones was called the Lady Barrington.

Thus potentially giving us five names for the five 'original' engines —

Dart, Tallyho, Star, and Fox and Lady Barrington. The

Barrington family have limited connection to the Lyons of Hetton, but

specifically Lady Barrington has a direct line to the Liddells who part-owned

Killingworth, the obvious potential source for the 'other' second hand engine.

Remembering that 'Steam Elephant' was a contemporary generic rather than

individual name, this leaves the slim but real possibility that, at least

while at Hetton, our Wallsend engine was named Fox; the first name

discovered for any Chapman engine.

The Stephensons rapidly fell from grace at Hetton and the ousting of Robert

(the brother) an embarrassing fiasco. Numerous reports were commissioned

by the owners, even including a detailed one from Chapman in July 1823, which

was at times highly critical and, interestingly, included the suggestion

that another locomotive may be needed. Soon, however and for some time to

come the railway had more engines than it needed, as increased output from

the group favoured the introduction of more stationary engines to avoid

bottlenecking. It is possible that the opening of Elemore, under way in 1825,

could well have prompted the acquisition of a suitable banking engine to

help out until the rope haulage system was in place.

Interestingly this date coincides with another change at Hetton which may

be of significance. The little-known Joseph Smith is first encountered as

an enginewright in 1813 at Heaton colliery and is almost certainly responsible

for rebuilding the Chapman/BuddIe engine there to BuddIe's specification

in 1821 to become Heaton II. In 1822 he is recorded building a BuddIe and

Chapman 'travelling engine' for Rainton and Pensher collieries. As a previously

unrecognised locomotive builder Smith requires much greater study.

By April 1824 Smith was working at Hetton, indicating that the rigid demarcation

between BuddIe and Stephenson spheres of influence may have started to fade.

Matthias Dunn wrote 'Joseph Smith is making very extensive alterations with

the machinery of this Colliery - particularly with the double engines, so

whimsically erected by Stephenson...91', the double engines being the stationary

engines there. On 25 June 1824 Mowbray writes to Wood 'I have engaged a man...'92

- the man is Joseph Smith and by December 1825 he is 'Company Engineer'93

at Hetton, in succession to Robert Stephenson. By 1827, he is described as

'Master of the Engine Wrights and Machine Makers' at Hetton with 12 men under

him and being paid £150 pa94. When dining with George Stephenson in

1828, Horatio Allen was given one side of the events and wrote,

'His son [sic] was desirous of being the chief Agent on the road, but the manoeuvres of a Mr Smith succeeded in obtaining for himself the situation. The result of the contest was a good deal of ill will between the parties. And when a new engineer was appointed in the interest of Mr Smith, their great desire was to do away as much as possible with the work and plans of Mr Stephenson, their predecessors.'

If the 'Steam Elephant' did indeed get to Hetton as a second hand

locomotive, here we have the perfect agent to effect the move.

In 1825, Buddle was busy gathering evidence against the Liverpool and Manchester

Railway Bill, on behalf of the canal company. He wrote to Chapman on the

subject of railway operating costs and suggests that, as a source of information,

'Joe who managed our locomotive on the Hetton way may be as fit as any'96

(my emphasis).

At present much of this evidence remains circumstantial, although Buddie's

letter makes no sense at all if not confirming the presence of a Buddle and

Chapman engine at Hetton. By Rastrick's visit in 1825, there are five engines

at Hetton and an 1833 valuation of Wallsend colliery98 showed no locomotives

left there; in other words if our Elephant did still exist at that date,

it had gone somewhere else. So perhaps in 1825, as events further south dominated

the railway stage, assisted by Smith, 'Nellie' had packed her trunk and slipped

away...

The final discovery to date is another illustration, in the private collection

of the railway historian John Fleming. Again a title page vignette, this

time on an unsigned manuscript book Sections of Different Seams of Coal in

the Counties of Durham and Northumberland. The paper is watermarked 'Whatman

1819' but otherwise there is once again no specific reference to provenance

or locomotive. The illustration gives no more insight than to clearly show

the same type of locomotive in a riverside colliery setting and to further

emphasise the regional location.

Conclusion

There is much work still to be done on the Buddle and Chapman' school' of

locomotive building, both to more fully understand their numerous engines

and applications, and the reasons why they fell into obscurity. BuddIe was

a giant in his own field; Chapman was highly respected, but principally known

as a civil engineer, and already an old man in the pioneering period. Neither

had families who would fire off a broadside of biased claims on their behalf

later in the century as others did, neither were trying to establish railway

'systems' or indeed make their fortunes. They were simply introducing a new

technology in a variety of forms of application, into an industry which was

growing at an unprecedented rate of investment and innovation and at a scale

hitherto unimagined.

Wallsend colliery was at the forefront of this new order, and as an unequalled

generator of wealth was, in many ways, the epitome of it. When a symbol of

this was required, what more natural than the new form of haulage to be seen

there? It is in this way that these puzzling and unexplained images have

come down to us, not necessarily as the most famous engine of its day, but

as the one at the most famous colliery .

Mountford, Colin E. Rope haulage; the forgotten element of railway

history. 171-91.

The author overstates the neglect of his topic: anyone who used the

East Coast main line was well aware of the rope-worked inclines fron Ferryhill

northwards. Nevertheless, it does need to be restated that rope haulage was

quite normal in County Durham and it lasted longer than main line steam.

There were two types of self-acting incline: the less common employed two

ropes and two drums; the more common type employed a single rope and a large

drum with brakes at the top of the incline. There were also powered inclines:

some used stationary engines supplied by locomotive builders (Hawthorn, Joicey

and Braclay) whilst others came from general engine builders, e.g. Robey

of Lincoln. Electric haulers gradually took over. Powered lines often included

curves. Two specific lines are noted: Starrs Bank Head at Wrekenton and

Ravensworth ann Colliery where the line traversed the Great North Road at

Low Fell. Inclines are preserved on the Bowes Railway. On lines which both

ascended and descended amin-and-tail haulage was practiced. Endless ropes

were also applied which were used frequently underground..

Boyes, Grahame: An alternative railway technology;

early monorail systems. 192-207.

Joseph von Baader (1763-1835) was granted a British Patent 3959/1815

(15 November 1815) An improved plan of constructing railroads and carriages

to be used on such improved railroads. To use one or two cast iron rails

(if two not greater tah 24 inches apart) to peovide horizontal guidance and

reduce friction. Henry Robinson

Palmer patented a suspended monorail on 22 November 1821: 4618/1821.

Systems developed at Royal Victualling Yard, in Deptford and at Cheshunt

in Hertfordshire. Latter used to convey bricks andd lime ¾ mile down

to River Lea and return with timber and coal. Opened on 25 June 1825.

Maxwell Dick of Irvine patented a

high level system on 21 May 1829 (5790/1829). This was claimed to avoid blockage

by snow and permit mail to be conveyed at 60 mile/h. Also mentions the Royal

Panarmonium Gardens, near King's Cross where a passenger carrying suspended

monorail operated in a fairground mannar from 4 March 1830..

Gibbon, Richard: Rings, springs, strings and things; the national

collection pre 1840. 208-16.

Early safety valves: weighted systems led to serious loss of steam.

Hackworth designed spring loaded systems and these were subjected to test

and hysteresis loops were produced. A modern locomotive safety valve was

also tested.

Clarke, Mike: The first steam locomotives on the European

mainland. 219-32.

In 1814-15 two Prussian engineers, Eckhardt and Krigar visited Leeds

and Newcastle to inspect Blenkinsop locomotives. This led to the construction

of two locomotives of the type in Berlin. These were smaler than the British

locomotives, but very detailed drawings survive. The first was sent to the

Chorzow Ironworks and the other to the Saarland.

Cowburn, Ian: The origins of the St Etienne rail roads, 1816-38;

French ndustrial espionage and British technology transfer. 233-50.

Gamst, Frederick C: The transfer of pioneering British railroad technology

to North America. 251-65.

MacDonald, Herb: The Albion Mines railway of 1839 - 1840; some British

roots of Canada's first industrial railway. 266-77..

Bailey, Michael R. and Glithero, John P: Learning through

restoration; the Samson locomotive project. 278-93.

Samson was built at Shildonby Hackworrth under sub-contract from George

& John Rennie in 1838 for use on the export of coal from minees at Stellarton

to the port at Pictou in Nova Scotia. The value of a detailed survey was

demonstrated. Not only has new light been thrown onto 1830s locomotive

manufacturing practice, and specifically that at the Soho Works in Shildon,

but also of mid-nineteenth century maintenance practices, about which very

little has been recorded. As has also been demonstrated with the surveys

of Albion and Braddyll, it was the practice of early industrial

railways to seek to keep their locomotives operating for as many years as

possible without the costly replacement of boilers and other major components.

The maintenance artisans were inventive and adopted practices that were,

for the most part, not recorded, but were passed down from master to apprentice

and improved upon with each generation. The longevity of industrial locomotives

contrasted with main line railways, whose locomotives were given extended

lives, usually through rebuilding or component replacement, to meet enhanced

operating specifications. The few surviving pre-1840 industrial locomotives

therefore provide a remarkable opportunity to add to our knowledge of materials

and manufacturing processes, providing a most informative second resource

to add to archive-based research into manufacturing history.

Banham, John. Coal, banks and railways. 297-310.

There were two Darlington banks: the Darlington & Durham Bank

of Mowbray & Co in which Arthur Mowbray (1755-1840) was a senior partner

and the Quaker bank of Backhouse & Co.. The latter was a model of probity,

the former was involved in entrepreneurial activity which included mining

and railways. Finance from Backhouses' Bank was vital to keeping Hetton going

in 1823 when Mowbray's initial capital raised two years before in London

was exhausted. It is also clear that Backhouses' Bank expertise and finance

were fundamental to ensuring that the |Stockton & Darlington Railway

was a success in 1826.

Stokes, Winifred. Early railways and regional identity.

311-24.

Baldwin, J.H. The Stanhope and Tyne railway; a study

in business failure.325-41.

Considers two key factors: the excessive reliance placed upon the