North British Railway Study

Group Journal Number 140-159

Key to all Issue Numbers

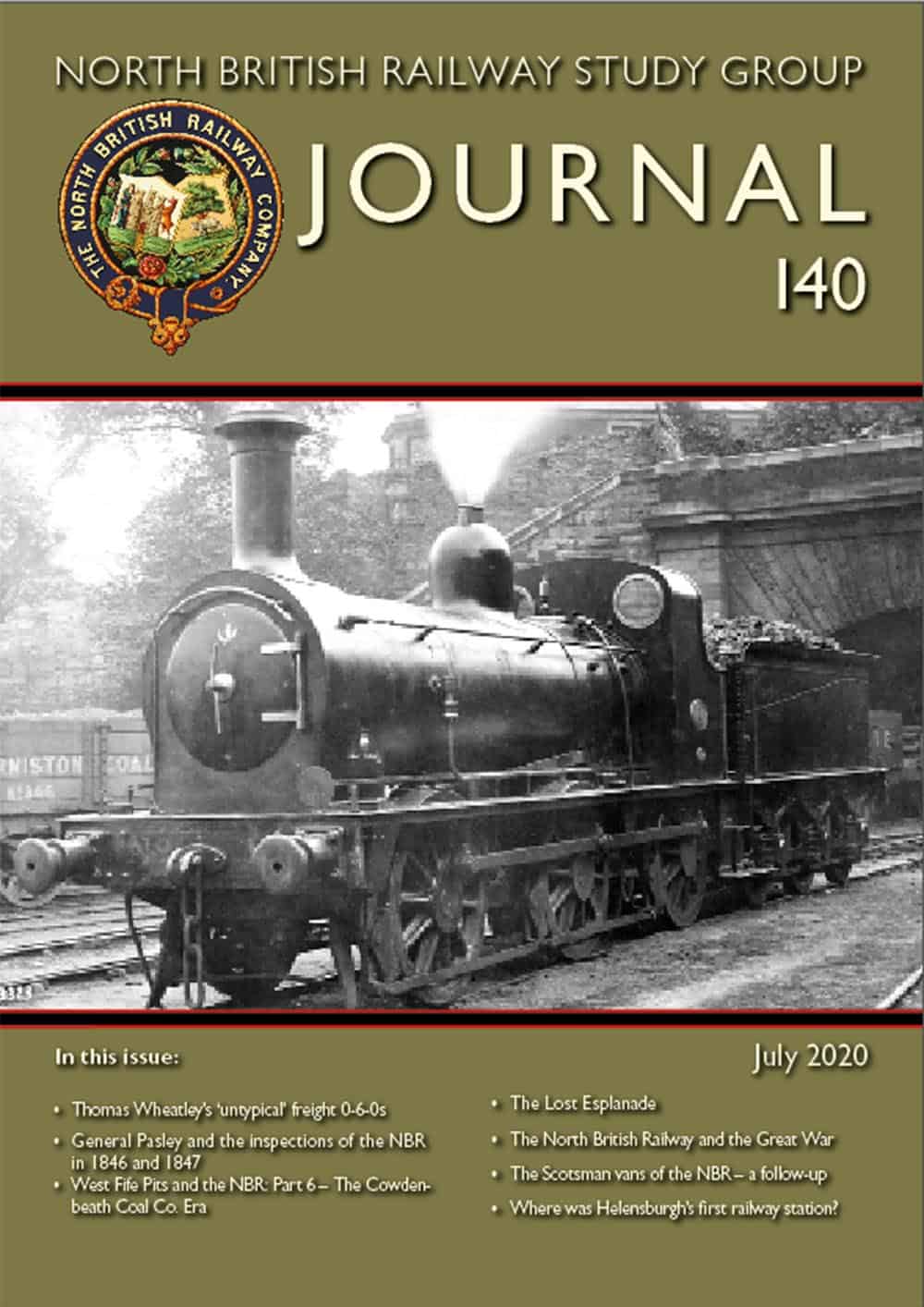

NBR No. 1, an 0-6-0 originally |

|

No. 140 (August 2020) |

Obituary Alasdair Alexander (Sandy) Maclean. 3

Born in Edinburgh, Sandy lived in Morningside Road in a flat overlooking

the Edinburgh Suburban line. After an education at George Heriots School

he joined the railway as a Junior Clerk at Newington. He served his two years

National Service in the RAF before returning to Morningside Road as a booking

clerk. He was successful in being selected for Management Training and one

notable job was head of the Coaching Plant section in the Operations department

of ScotRail HQ in Glasgow where he made a particular impact on revolutionising

carriage cleaning with the introduction of more scientific methods. Living

in Greenock, Sandy seldom strayed from his home in his latter years. "Sandy

was, in railway terms, without a doubt in my mind one of the most informative

and intelligent people I have ever met. Always ready to help he was a true

gentleman". Includes a portrtait.

Euan Cameron. Thomas Wheatleys

untypical freight 0-6-0s. 4-16

First batches built in 1870-1, before a larger,more homogeneous series

appeared in 1873 [already discussed and illustrated

in Journal issue No. 138, pp. 9-13]. These "very plain little engines

shared the characteristic robustness and solidity of all Wheatleys

locomotive chassis, and after rebuilding most ran until the First World War.

A few survived beyond the end of hostilities."

Wheatley rebuilds of R. & W. Hawthorn 0-6-0s of the 64 series, J110 in

the Group List, 1921 diagram book 70

When Wheatley succeeded the disgraced William Hurst as Locomotive Superintendent

of the NBR in 1867 he faced an urgent need to improve or replace, that part

of the surviving stock of locomotives which had been built before the middle

1850s, derived both from the N.B. itself and from absorbed constituent companies.

In the case of the North British itself, 70 of the first 71 locomotives had

been built by R. & W. Hawthorn of Newcastle upon Tyne. The Hawthorns

had a fatal design flaw which went back to their origins in the Stephenson

Patentee design, the consequences of which became worse as the

engines grew larger [see Journal No.

128, pp. 3-4 for a fuller discussion, also

D.K.

Clarks Railway Machinery, vol 1 p. 233]. The key document

prepared at Cowlairs from 1867 onwards, known to devotees as the Cowlairs

1867 List was essentially a record of the necessary replacement, one

for one, of the vast majority of this early stock.

Some of the very last NBR Hawthorn 0-6-0s were reconstructed in such a way

that their successors counted as rebuilds rather than replacements. They

are described here as fully as possible, and it is up to the reader to decide

whether rebuilding is an apt description or not. The general

arrangement of the original Hawthorn 0-6-0s Nos. 64-71 of 1850-1 has not

survived, but it is believed that photograph of Edinburgh

Waverley East End by the early photographer Thomas Begbie shows one taking

water. The engine has heavy outside sandwich frames and judging

by the presence of angled supports from the outside frame to the boiler

appears to have had the slender and ineffective inner framing which stretched

from the cylinder block back to the firebox. The firebox was larger in diameter

than the boiler barrel, which was domeless. According to the description

in the Cowlairs list, these original engines had 17-ft by 24-in cylinders,

lined up to 16-in diameter in some cases, and 4-ft 9-in diameter wheels spaced

7-ft 4-in + 6-ft 8-in apart. Some accounts claim that the engines began their

existence with 18-in bore cylinders but had to be reduced almost immediately.

Sandwich-framed six-wheel tenders were supplied. The rebuilding

of these locomotives occurred between 1868 and 1872. In association with

their rebuilding but slightly after a most peculiar renumbering

took place, by which (apparently) 64/5/6 were renumbered 9-11, and 70 was

renumbered 14. Surely Nos. 67-8 should have become 12 and 13, but that change

never happened. No. 67 was rebuilt at St Margarets in 1868 with similar

wheels and cylinders to the original, with the coupled wheelbase adjusted

to 7-ft 4-in+ 7-ft 6-in. A domeless boiler was fitted, similar to the original

but with a flush rather than raised firebox. The remainder, 64/9, 65/10,

66/11, 68 and 70/14 were all rebuilt at Cowlairs. The rebuilding list gives

them 4-ft 6-in wheels, except that 14 received 5-ft 0-in wheels (an anomaly

confirmed by photographs). In all cases the Cowlairs rebuilds had their axles

spaced 7-ft 3-in + 7-ft 9-in The outside frames were dismantled and rebuilt

with the large plates carrying the axlebox horns reassembled on to a new

longitudinal frame. But with No. 14 it is likely that the hornplates

were completely new, as those on the rebuilt engine were trapezoidal shaped

with straight sides, rather than the concave curves seen on the others.

All these rebuilds received new inside mainframes, running the length of

the engine from buffer- to drag-beam, with additional bearings for the driving

axle. The massive structure created by the four full-length frames secured

back and front will have done a much better job of keeping the cylinders

and axleboxes in correct alignment. The cylinders of all except No. 67 were

16-in bore x 24-in stroke, a standard size for Wheatley goods locomotives

and used on nearly all the engines discussed in this article.

The boilers of the rebuilds were quite different from the originals, as the

latter will have had a firebox too wide to fit between the inside frames.

It is likely that the Hawthorn rebuilds received something like

a Cowlairs standard boiler of the 1865-1870 period, with an approximately

4-ft 0-in diameter barrel 10-ft 2-in long and a flush round-topped firebox

5' 0" long. A large proportion of Wheatleys engines received a version

of this boiler. In the pre-1871 period such boilers were typically domeless

with a safety-valve trumpet over the centre of the firebox crown, with the

trumpet part located on a square base with a flat top. As first

built, they possibly had Salter safety valves, but Wheatley replaced these

in the early 1870s with direct-loaded sprung valves entirely enclosed in

the trumpet. Some engines (10 and 68 as far as we know) received open-topped

dome covers over their safety valves in place of the Cowlairs trumpets, probably

purloined from other engines; but these did not enclose a steam dome.

Weatherboards were fitted, sometimes with bent-over tops, and 68 was given

a facsimile of an enclosed Wheatley upper section to its cab, probably in

the 1880s. The 1870s recreations of the Hawthorns carried reconstructed outside

frames to different dimensions from the originals, and all new wheels, inside

frames, boilers, and platework. Does this count as a rebuild

or a new construction? One reason to describe them as rebuilds may have been

financial: renewing an engine with the same number as a predecessor allowed

the cost to be written down to repairs rather than new building.

Given the (theoretical) age and chequered history of these rebuilds, it might

surprise that Matthew Holmes gave four of them a fresh lease of life by

rebuilding them yet again: yet he did. The rebuilding in this case involved

a reboilering, with the addition of locomotive steam brakes, updated boiler

fittings, and a Holmes round cab. No. 11 was rebuilt in 1884, 10 in 1886

and 9 in 1896. 68 was rebuilt at some point around 1900, the precise date

not certain. Nos. 67 and 14 were not rebuilt. The boilers were of what is

presumed to have been the same size as the 1870s versions, but with all

Holmess characteristic fittings. The barrels were 10' 2" long and the

fireboxes 5' 0" long. There were 171 tubes x 1¾-in diameter, tube heating

surface of 817 ft2., firebox heating surface 83.5

ft2., total 900.5

ft2. Boilers with these identical dimensions were

also fitted to the Longbacks and the No. 1 series 0-6-0s (as below) when

rebuilt. The tenders attached to the rebuilds were generally borrowed from

other 0-6-0 locomotives and varied greatly. It must be presumed that as the

engines left Cowlairs they were simply allocated whatever tender happened

to be available. Some of the tenders from R. & W. Hawthorn locomotives

long outlived their original locomotives, coupled to other engines altogether;

yet curiously very few Hawthorns actually kept their own tenders.

Wheatley No. 59 series of reconstructed 0-6-0s, sometimes known as

Longbacks, J124 in the Group List, 1921 diagram book 71

Between 1868 and 1869 Wheatley also constructed eight double-framed 0-6-0s

at Cowlairs, in many respects very similar to the rebuilt Hawthorns. These

engines were assigned random numbers of dismantled locomotives and have therefore

been regarded as replacements rather than rebuildings. The most striking

difference between these engines, known unofficially as Longbacks and the

rebuilt Hawthorns is that most of the engines built new (with the exception

of 154/5) received substantial, deep, slotted frames of continuous metal

plate outside the wheels as well as inside. The resulting mainframes will

have been exceptionally robust, and the locomotives worked for many years.

154 and 155 had composite outside frames with hornplates riveted to a

longitudinal iron beam, more in the manner of the Hawthorns but with a different

profile to the hornplates. Photographs of 135, 154

and 155 survive in their original condition.

Miscellaneous locomotives rebuilt with double frames and outside cranks in

the 1860s-1870s

Besides the more or less identifiable classes of outside-framed

0-6-0s, there was also a handful of individual locomotives, mostly reconstructed

from Hawthorn material, but associated with different original company owners

and often with rather unclear histories.

No. 17

Double-framed 0-6-0 No. 17 appeared from St Margarets works in 1869.

Theoretically it was a rebuild of one of the original Hawthorn

0-4-2s supplied to the N.B. before it opened, but in this case little or

nothing of the original engine can have been incorporated in the rebuild.

No unambiguously identifiable image of the locomotive in its 1869 condition

survives; but one may assume that the boiler and fittings were similar to

those of No. 67. The outside frames, however, were of the same deeply slotted

continuous plate as on most of the Longbacks, which were of course Cowlairs

engines. 17 had 4-ft 7" wheels spaced 7-ft 6-in+ 7-ft 6-in. Holmes rebuilt

17 in either 1896 or 1898 (sources differ) and it was attached to a tender

purloined from a Neilson 90 Class 2-4-0 of 1861 (all but one of which had

by that time been scrapped). It was long associated with Thornton shed, where

it seems to have been used on service trains.

No. 50

No. 50 was an exceptional survival from an earlier series of Hawthorn 0-6-0s,

Nos. 47-54. It was comprehensively rebuilt in early 1869 in the same way

as 67, retaining its distinctive curved outside frames. As rebuilt it had

4' 2" wheels with conventional spokes, spaced 7-ft 6" + 7' 6". It was rebuilt

in 1882 (probably by Holmes although it retained some Drummond aspects to

the boiler fittings) and lasted as No. 1030 to late 1910. It was attached

to one of Wheatleys scrap 4-wheel tenders with a chassis constructed

of very thick wooden baulks at the sides and ends, to which strengthening

plates were riveted. It served as the Carlisle Canal trip pilot for some

time.

Two others of the same series, 47 and 52, were rebuilt at Cowlairs in 1874

and St Margarets in 1868 respectively. Neither received a second rebuilding

and they appear to have escaped the attention of photographers. Nos. 137-9

137-9 were three 0-6-0s supplied by Hawthorns to the Edinburgh, Perth and

Dundee Railway in 1851. 137 and 138 were rebuilt at Cowlairs in July and

May 1868 respectively. They had 5-ft 0" wheels and typical Hawthorn outside

frames, probably spaced 7-ft 2-in + 6' 6-in. Neither received a second

rebuilding. 137 retained a massive six-wheeled Hawthorn tender, and was based

at Dundee.

Nos. 249-50

Two Neilson 0-4-2s were supplied to the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway in

1851. According to the Cowlairs 1867 List, they were replaced by two engines

of the same numbers built at Cowlairs in December and October 1867 respectively:

but the list describes them as 0-4-2s with 5-ft 0-in wheels spaced 7-ft 9-in

+ 7-ft 1-in. 250, at least, was definitely a 0-6-0 incorporating Hawthorn

material, though the reported wheelbase may well be correct. In the early

1890s it was photographed at Cowlairs with a domeless boiler with lock-up

safety valves over the firebox crown, and a box lower section to the cab

surmounted by a partial upper section of vaguely Drummond appearance. In

1896 it was rebuilt by Holmes with his usual fixtures and fittings.

250/873/1073 had a Stephenson 4-wheel tender before its second rebuilding

and a Wheatley 6-wheel 1,800 gallon tender when photographed at Ladybank

in the 1900s.

No. 280

280 was somewhat unusual although resembling those discussed above in general

layout. It was reportedly built at Cowlairs in 1865 as a 0-6-0 with 4-ft

9-in wheels spaced 7-ft 7-in + 7-ft 6-in. It had the usual Cowlairs boiler

of the period, but the flat weatherboard had an arched top, and bulged outwards

around the spectacle plates before narrowing down to join the lower section

of the cab. This style of weatherboard appears also to have been used on

2-4-0s 235/6/9 built around the same time. It received a 6-wheel tender similar

to that attached to 68. 280 lasted long enough to receive its 800 series

number after 1895, though it was not rebuilt by Holmes. The No. 1 and 2 series

inside-framed 0-6-0s built with 4-ft 2-in wheels and 7-ft 3-in + 7-ft 9-in

wheelbase, 1921 diagram book 41

The final classes to be reviewed here were two batches of goods 0-6-0s of

great simplicity and solidity, built for slow mineral traffic around 1870-1871.

Unfortunately some inaccurate information in print makes it at times difficult

to distinguish between the two series, which differed in wheelbase from their

first building onwards.

Twelve 0-6-0s were built, mostly in 1870-1, with solid slotted inside frames

similar to those on 0-6-0ST No. 220 [see issue No. 138 pp. 6-7] with which

they shared wheel sizes and wheelbase, 4-ft 2-in wheels spaced 7-ft 3-in

+ 7-ft 9-in. As one of the class was given the number 1 released by the scrapping

of the original Hawthorn 0-4-2, they became known as the 1 class. The Wheatley

0-6-0 so numbered retained that distinction until it became 1150 and its

capital number was taken over by a Reid 4-4-2T.

According to some records, including official ones, the first of the class,

No. 251, was built as early as 1867, but its design similarity to the other

engines makes this rather unlikely. The 15-ft 0-in wheelbase engines had

inside frames only, no brakes on the locomotive, very simple domeless boilers

with safetyvalves over the firebox crown, and simple weatherboards above

the cab side-boxes. The cylinders of all these engines were 16-in x 24-in.

They received Wheatleys 1,800 gallon tenders. Matthew Holmes rebuilt

all twelve locomotives between 1894 and 1900, slightly increasing the wheel

diameter to 4-ft 3-in with thicker tyres and raising the running plate height

accordingly. The rebuilds received the same boilers as the rebuilt Hawthorns

and Longbacks, and were fitted with locomotive brakes for the first time.

The tenders were not altered.

Between October and December 1871 Wheatley added 6 more locomotives but these

from first construction differed from the original 12. The latter six engines

(known as the 2 class) had wheelbases 6-in shorter than the previous

twelve, at 6-ft 9-in + 7-ft 9-in. While photographs of this class in original

state are extremely rare, a picture of 223 shows it to have had a boiler

with a dome on the centre of the barrel. By inference from the data from

the rebuilding, it may be supposed that these boilers had a barrel 9-ft 7-in

9-ft 10-in long and a firebox 5-ft 0-in long. The 2 class later formed

the basis for the much more numerous and better recorded 430

class, which they resembled in wheelbase and cylinder sizes.

Matthew Holmes rebuilt all six between 1887 and 1901. They received the shorter

boilers already designed for the rebuilt Beyer, Peacock locomotives formerly

of the E. & G.R., with 9-ft 7-in boiler barrels and all Holmess

usual fittings. Most if not all of these locomotives appear to have been

attached to Wheatley 1,800 gallon six-wheel tenders throughout their

existence.

Most of the 1 and 2 class lasted until withdrawal between 1913 and 1915,

by which point they were over 40 years old. Some lasted in traffic until

1920, and 1196 ex 252, with possibly others, survived long enough to carry

its duplicate number in large control numerals on the tender. By that stage

most of these early locomotives were in use as yard pilots or for very short

trip workings. As an example, when No. 2 was a pilot at Portobello it was

also regularly assigned to a trip goods to Dalkeith. There are oral traditions

concerning the allocations of many of these locomotives, but as the traditions

often contradict each other, they are omitted here as unreliable. It is

remarkable that well into the 20th century North British Railway yards would

have seen locomotives shunting and running short trip goods, which had their

origins dating back to the 1860s or even the 1850s. The N.B. was a very cautious

and parsimonious railway (by and large) and Matthew Holmes in particular

seems to have been determined to make good use of any serviceable material

that could be found. The only critique that one might make of keeping such

venerable antiques in traffic was that when so many 1860s locomotives had

to be withdrawn within a few years after 1910, the N.B. was left with a shortage

of locomotives, which plagued it until after grouping even despite the

proliferation of more modern engines. Meanwhile these quaint old engines

kept the cadre of N.B. engine photographers well occupied

| Thomas Begbie photograph of NBR Hawthorn engine of the 64-71 series, at Waverley East c.1860. | 4 |

| No. 10, previously No. 65, at work, marshalling goods train. Note dome cover probably taken from another engine, and Dübs tender. 1880s? | 5 |

| No. 1016, previously No. 66, at Ladybank. This shows the locomotive as rebuilt by Holmes. | 5 |

| Wheatley Longback 0-6-0 No. 135 before rebuilding, with Dubs tender: dark olive livery applied in Drummond period (Euan Cameron coloured drawing). | 6 |

| Wheatley Longback 0-6-0 No. 135 after rebuilding by Holmes in 1894: fully-lined out Holmes livery as depicted in multiple photographs from period. Locomotive brakes (not shown here) added some time after engine rebuilt. (Euan Cameron coloured drawing). | 6 |

| NBR No. 68 at Kilsyth Old Station. View shows wealth of other detail including brake van and wagons and semaphore signals | 7 |

| Wheatley Longback 0-6-0 No. 135 as running before rebuilding. This is the condition of locomotive seen in photograph taken at Anstruther in 1887. Note short sloped cab roof wrapped around curve of weatherboard. | 8 |

| Longback 0-6-0 No. 135 after rebuilding in 1898. Note details of construction of mainframes, perpetuated from original condition but very different from 135, and Wheatley short-wheelbase tender. | 8 |

| On left No. 135 after rebuilding with New NBR engine alongside is Atlantic No. 878 Hazeldean | 9 |

| No. 135 in unrebuilt condition, photographed at Perth. | 9 |

| No. 155 as rebuilt by Wheatley, at Anstruther in January 1887 | 10 |

| No. 1018, previously No. 17, with breakdown train at Thornton, some time between 1901 and 1914. Leftmost figure on ground possibly Christopher Cumming | 10 |

| No. 50, a St. Margarets rebuild of 1869. Note the distinctive St Margarets works plate on the frame. | 11 |

| No. 1 of 1870 in original condition. It was later rebuilt, in 1898. Note steam pipe leading down from firebox crown towards to the injector has been removed, as has the whistle, so the engine was probably under repair. Dome cover was later addition. | 11 |

| 0-6-0 No. 1 as running in the Drummond and Holmes period before rebuilding. While a photograph taken of this engine in the early 1890s shows a dome cover over the safety valves, the form of safety valve cover shown here was the original, and appears in multiple other photographs of the class. | 12 |

| No. 1196, previously No. 252, with control number on tender. Possibly at Armadale in 1916, driver Thomas Marshall. (Hennigan collection) | 13 |

| No. 2 at St. Leonards after rebuilding. Note young visitor on running plate. (Hennigan collection) | 13 |

| No. 2 as running soon after rebuilding in 1888, in the livery of the period | 14 |

| No. 17 as renumbered 818 in full Holmes livery. Note low-pitched boiler, steam brake for locomotive, and tender from Neilson 2-4-0. | 14 |

Carriages. 17

| Train of four-wheel carriages hauled by 4-4-0T No. 1465 (later LNER Class D51), at Abbeyhill, heading for Edinburgh Waverley. (NBR Photo Archive 20568 |

| 6-wheel non-vestibuled 6-compartment third class carriage at Meadows Yard, carrying LNER No. 31433. (Hennigan Collection) |

| NBR bogie non-vestibuled lavatory semi-open third class non-gangwayed carriage No. 31246 (former NBR No. 1246), NBR 1908 diagram 6,NBR 1920 diagram 6, LNER diagram 6B, built for West Highland Railway. Vehicles originally had large picture windows in the centre saloon which lacked ventilation, and altered to form shown. (Real Photographs) |

Donald Cattanach. General Pasley and the inspections

of the NBR in 1846 and 1847. 18-27

Adds much to our understanding of

General Pasley and the development

of early railway inspections for the Board of Trade, especially under

Dalhousie. It also summarises

the effects of the British climate upon a "difficult" section of the East

Coast Main Line which is prone to flooding and severe coastal erosion; both

factors being exacerbated by Global Warming. Includes a reproduction of the

letter sent by Pasley to Dalhousie on 18 May 1846 recording his (first)

inspection of the line. This is also intersting in that it also records his

inspection of the tubes being manufactured in Manchester for the Menai crossing.

Pasley was accompanied on the inspection by

Charles Jopp, Resident Engineer,

and his assistant, and by James Bell,

also then in the employment of the Engineer of the line,

John Miller, but who would

be appointed the NBRs Resident Engineer on the opening of the line

(and, later, its first Engineer-in-Chief).

Pasley's inspection took place within a day and he found some of the structures

extremely sound, but others were very poor including two bridges which were

required to be rebuilt. Some included rubble stone. The line was not sanctioned

to be opened. Pasley returned on 17 June 1846 to inapect the formerly unsound

structures and did permit the opening on 22 July. On 31 July subsidence at

Markle caused the 04.30 southbound mail to derail. Both the drivver and

locomotive superintendent Robert Thornton

who was also on the footplate escaped with severe bruising. Thornton

also drove Pasley around by locomotive. On 28 September the area experienced

torrential rainfall and the line was severed in several places, notably

at the crossings of the Eye Water and the Tower Burn south of

Cockburnspath.

Includes the Penmanshiel Tunnel tragedy on Saturday 17 March 1979, when workmen

lowering the base of the tunnel were entombed in a major rockfall wwhich

led to the railway being diverted onto a new alignment.

| General Pasley portrait (colour) | 11 |

| The North British Railway and other lines in 1847. | 21 |

| Part of Berwickshire, showing locations mentioned in the text | 21 |

| Lamberton Holdings: part of railway wall in foreground, indicating original track alignment, swept away by landslip above farm at Lamberton Holdings* | 22 |

| Megs Dub on 20. June 2020: name possibly relates to arrival in Scotland on 1 August 1503 of 13-year-old Margaret Tudor, daughter of Henry VII of England, for her marriage to James IV of Scotland.. | 23 |

| Another view of Megs Dub. | 24 |

| Caravans occupying original track alignment at Marshall Meadows. Satellite image (Google Earth) | 25 |

* The present alignment is much closer to the cliff face, which is covered with netting to stabilise the bank. The A1 road runs at the top of the cliff. On Saturday 20 June 2020, the 1E11 from Edinburgh to St Neots is traversing the 90mph section, nearing the Scottish Border.

Alan Simpson. West Fife pits and the NBR: Part 6 the Cowdenbeath

Coal Co. era. 28-37

Area comprises parishes of Ballingry and Beath and town of Cowdenbeath

and village of Lumphinnan. Kelty descibed in Journal

136 and Lochgelly in Journal 139.

Predecessors to the North British Railway: The public railway system came

to the area in the late 1840s with the opening on 4 September 1848 by the

Edinburgh & Northern Railway (E&NR) of the line from Thornton to

Crossgates. This line, which ran to the east of the present day town of

Cowdenbeath, had stations locally at Cowdenbeath and at Crossgates. The

E&NR changed its name to the Edinburgh, Perth and Dundee Railway

(EP&DR) from 1 August 1849. The line was later extended to Dunfermline

on 13 December 1849 where it made an end-on junction at a joint station with

the Stirling & Dunfermline Railway later called Dunfermline Upper station

[following the closure of what was the eastern part of the Stirling and

Dunfermline the local Sheriff Court and a retail park are on its site].

The next local public railway development (lying between Cowdenbeath and

Lochgelly) was the opening to traffic in June 1860, of a junction, called

Lumphinnans Junction, between the EP&DR and a new local railway company

called the Kinross-shire Railway. This later line headed southwards from

Kinross, where it had made an end-on junction (and had a joint station) with

yet another local line called the Fife & Kinross Railway which The

EP&DR itself in turn was vested in the NBR on 1 August 1862 and this

brought the NBR to Fife. Much later, the public railway layout of the area

was transformed by the building of new lines which were part of the overall

Forth Bridge approach railways which opened in the early 1890s. Their

construction was undertaken by the NBR as part of the creation of a continuous

double-tracked trunk route from the Forth Bridge to Perth (in part by upgrading

existing lines but in others by building entirely new stretches of line).

In Fife and Kinross-shire these lines were:

An entirely new line from the northern landfall of the Bridge to

Inverkeithing;

An entirely new line from Inverkeithing eastwards to Burntisland where

it joined the former EP&DR;

Upgrading to main line standard the northern section of the former

Dunfermline and Queensferry Railway (from Inverkeithing to Townhill Junction

on the Thornton to Dunfermline line);

An entirely new line from Cowdenbeath Junction to Kelty;

Upgrading to main line standard of the line from Kelty to Kinross,

Milnathort and Mawcarse on the former Fife & Kinross Railway section;

An entirely new line from Mawcarse and through Glenfarg to Bridge

of Earn.

The Kelty Loop (Cowdenbeath Junction to

Kelty). From 2 June 1890, a completely new main line opened which left

the existing NB Dunfermline to Thornton line at a point named Cowdenbeath

Junction (later renamed Cowdenbeath South Junction) on the western margin

of Cowdenbeath and headed north to join the existing Lumphinnans Junction

to Kelty route at what was now called Kelty South Junction. Included with

this new line was a railway station named Cowdenbeath (New), located just

off the High Street and almost in the centre of Cowdenbeath itself . The

NBR renamed this original station Cowdenbeath (Old) as from 1 June 1890 and

it remained open for passenger traffic until 31 March 1919 and from then

on until 1 January 1968 for goods traffic only. These dates are per the late

D.M.Lindsays NBR Chronology. Cowdenbeath

(Old) survived in use for miners work trains for a period after its

closure in 1919 to ordinary passenger traffic. These miners trains

appear in the Working Timetables and typically ran from Dunfermline Upper

station to Kelty via Lumphinnans Junction in the early morning (around 6

am) with a return working in the mid afternoon after the end of the day shift

at the various pits. Quick mentions that

an engine based at Kelty worked miners trains which called here long

after public closure and refers to

Locomotives of the LNER: Part

8B and on page 66 of that work it is noted that Dunfermline

shed also numbered a dual-fitted J83 amongst its stock, No. 9831 [it became

BR No. 68478] which in addition to the normal shunting and trip duties undertaken

by the class at Kelty was also able to work short-distance passenger trains

(provided for miners) calling at Cowdenbeath (Old) Station long after its

closure to normal traffic...

Early 20th century railway developments in the area

Lumphinnans East and North Junctions

New loops were installed in April 1901 at both Lumphinnans East and Lumphinnans

North Junctions on the line from Kelty South Junction. This line was in fact

the original Kinross-shire Railway and until the recent construction of the

Kelty Loop had been the only route northwards from

west Fife (excluding the NBs freight-only former West of Fife Mineral

Railway which ran to the north-west of Dunfermline) to Kelty, Kinross and

Milnathort.

Cowdenbeath Loop (see Map 1)

The original NB main line westwards from Lumphinnans Junction to Cowdenbeath

(Old) and Cowdenbeath South Junction had, by the late 1890s, a number of

separate colliery sidings, such as those serving the Donibristle colliery

and the Raith pits of the Lochgelly Iron & Coal Co.

(see Part 5 of this series in Journal No. 139)

connected to it. In addition to these there was the Cowdenbeath gasworks

siding and finally, the NBs Kirkcaldy and District Railway opened in

March 1896 and ran from Invertiel Junction near Kirkcaldy to Foulford Junction

near Cowdenbeath.made a junction with the original main line at Foulford

Junction. As a result of the growth of traffic to and from the various pits

a diversionary route was built to allow through traffic to by-pass this congested

section of the original route. The new line (named the Cowdenbeath Loop on

large scale OS maps) ran eastwards from Cowdenbeath North Junction (which

lay north of Cowdenbeath (New) station) to Lumphinnans Central Junction,

where it joined the original main line from Thornton and Lochgelly. Today,

the Cowdenbeath Loop remains open for traffic on the Fife Circle trains.

The opening date for this new line was January 1900 and this is given on

page 106 of Thornton railway days; edited Lillian King (Windfall Books:

2000). Several other writers state that the Loop was opened to traffic in

March 1919 but:

The Cowdenbeath Loop is first shown on Sheet 40 (Kinross) of the 1

inch to 1 mile OS map revised in 1903/04 and published in 1906;

It is also shown on the Sheet XXXIVNE of the 6 inch to 1 mile OS map

revised in 1913 and published in 1920.

I suggest that the date of March 1919 was that from which all passenger traffic

in the area heading either east to Thornton Junction or west to Dunfermline

was re-routed via the Cowdenbeath Loop and Cowdenbeath (New) station. The

Cowdenbeath (Old) station had closed to passenger traffic as from 31 March

1919 and what had been the original main line (between Lumphinnans Central

Junction and Cowdenbeath South Junction) was now used mainly for freight

traffic but

| Cowdenbeath Coal Co. wagon, No. 856 (4-plank: 8 ton capacity? Lettered Lumphinnan Collieries, Fife C C C Ld | 28 |

| Map: NBR (later LNER) lines and private mineral lines in different colours extracted from Ordnance Survey One-inch Popular edition, Scotland, 1921-1930, Sheet 68 - Firth of Forth. 1928 | 29 |

| Map: Christie & Cos Iron Works. Edinburgh Perth & Dundee Railway main line and private mineral lines in different colours extracted from Ordnance Survey 6-inch First Edition, Fife and Kinross Sheet 31 1856. Survey date: 1854. | 31 |

| Map: Lumphinnan Iron Works and No. 1 and No. 7 Pits. NBR main line and private mineral lines in different colours extracted from Ordnance Survey 25-inch Second Edition, Fife and Kinross Sheet XXXIV.NE Publication date: 1896. Re-surveyed: 1894. | 33 |

| Cowdenbeath Coal Co. Ltd. 8 ton wagon No. 950, built RY Pickering, with spring buffers and steel underframe | 34 |

| Map: Cowdenbeath area. NBR lines and private mineral lines in different colours extracted from Ordnance Survey 6-inch Second Edition, Fife and Kinross Sheet XXXIV.SE shows the NBRs two main routes in the area, the old line with Cowdenbeath Old Station and the new line with Cowdenbeath New station. Extracted from Ordnance Survey 6-inch Second Edition, Fife and Kinross Sheet XXXIV.SE 1896. Re-surveyed: 1894. | 35 |

| NBR coal waybill from Cowdenbeath colliery (document from Lindsay Horne Collection, donated to NBRSG Archive) | 37 |

| NBR coal waybill from Hill of Beath Coal and Fire-Clay Works (document from Lindsay Horne Collection, donated to NBRSG Archive) | 37 |

| NBR coal waybill from Donibristle colliery (document from Lindsay Horne Collection, donated to NBRSG Archive) | 37 |

John McGregor. The lost Esplanade. 38-43

The first serious attempt to reach Fort William, by the the Fort William

Railway (1862) would have diverged from the Inverness & Perth Junction

at Etteridge (Glen Truim) or Newtonmore, running by Loch Laggan and Glen

Spean. Thomas Bouch made a preliminary

survey; but he could not persuade the landowners who had commissioned him

that they must seek outside capital to supplement their own slender resources.

The Glasgow & North Western Railway, a bill for which was lodged in 1882-3

was a highly ambitious and blatantly speculative failed becuse the landowners

were not prepared to allow railway construction on their land. The engineer

for this line was Thomas

Walrond-Smith. The West Highland Railway was more fortunate in that the

Napier Commission Report in 1884

had prepared the way for a railway to Fort William and onward to an Atlantic

port at Roshven with the prospect of Treasury assistance. The route from

Craigendoran to Fort William was engineered by

Charles Forman, was approved in

1889 and opened in 1894. It is treated here very much as a fait accompli.

The promoters carefully disciplined their parliamentary presentation; before

their Bill came to Parliament, they obtained the North British Companys

promise of a guarantee and working agreement; and they secured declarations

of support, or at worst neutrality, from every major proprietor along the

route. Moreover, both public and parliamentary opinion was broadly sympathetic.

A 30-mile extension to Loch Ailort (which the North British did not include

in their guarantee), together with a new harbour at Roshven, was added to

the West Highland Bill and by so doing the promoters staked a claim

for subsidy. Though the West Highlands Roshven arm was rejected in

the House of Lords, the Commons Committee concluded that the proposed line

to Fort William was justified, both on its own merits and as a step towards

a third railhead on the west coast, supplementing Oban and Strome Ferry.

The Highland Company, and the Caledonian too, miscalculated their opposition

they had expected the West Highland Bill to fail comprehensively on

the vexed question of government aid, and were slow to realise how far the

North British were already committed.

This article's main thrust is on the Fort William terminus and a possible

link to the pier by a tramway, thus creating an esplanade.

There is some suggestion that the North British sought primarily to intersect

the Callander & Oban, at the same time pre-empting any independently

promoted cut-off to Crianlarich which might pass into Caledonian hands. A

railway onwards from Crianlarich and across Rannoch Moor into Lochaber was

in itself a dubious proposition. But running powers to Oban might not be

granted, and Fort William offered a tempting bridgehead at which to wait

and see, pending further advance whether to Inverness by the

Great Glen, as most commentators expected, or to the west coast, if government

support were first assured. To forestall the former became the Highland

Companys priority. Judging the battle lost when the West Highland Bill,

shorn of Roshven, passed the House of Lords, they negotiated the Great Glen

Agreement, or Ten Years Truce and ceased their opposition in

the Commons (where the Caledonian fought on to defend Oban). By this Great

Glen treaty, any extension of the West Highland towards Inverness was postponed

for a decade after the commencement of traffic to Fort William. One more

point must be made. The Callander & Oban Company, worked at cost by the

Caledonian, enjoyed a meaningful measure of autonomy; but the West Highland

became, almost from the outset, the North British by another name,

and the promoters early pledges to their supporters, all along the

route, lay at the discretion of their paymaster-patron.

As authorised in 1889, the West Highland would have entered Fort William

through crofting land along the River Lochy, crossing the River Nevis on

a causeway to reach the old fort, the prospective site of the passenger station.

A new seawall along Loch Linnhe was to carry a connecting tramway to the

town pier; and, on the understanding that this would remain a tramway, the

burgh commissioners framed an enthusiastic petition-in-favour. They expected

to obtain an open promenade-cum-carriage drive behind the seawall, with tramway

traffic limited to an unobtrusive shuttle, linking station and steamers.

Edinburgh solicitors MacRae, Flett & Rennie, the principal agents for

the promoters and subsequently for the West Highland Company, made no commitment

in so many words but they gave every assurance that the interests of

Fort William would be kept in view. The fort was acquired by Campbell

of Monzie, whose wife, Christina Cameron, had inherited the Lochaber estate

of Callart and was feudal superior of the burgh and later she made over the

fort site to the West Highland Company. Forman acknowledged that, in taking

the West Highland across Rannoch Moor and down Loch Treig into the Spean

valley, he had copied the drove-road proposed by Thomas Telford at the beginning

of the 19th century.

During the interval, when it seemed that the Callander & Oban might halt

permanently at Tyndrum, narrow-gauge feeder lines had been suggested, both

from Oban and from Lochaber. One such was the Fort William, Ballachulish

& Tyndrum Railway (1874), running by Glen Coe. This probably speculative

scheme had progressed to a notice of intent only to fade away when

standard-gauge construction onwards to Oban was resumed. It would have terminated

at Fort William pierhead, half-a-mile from the fort, entailing only the

demolition of decayed property in the towns west end.

The railway was almost complete and ready for inspection, but the terminus

problem remained unresolved and the Board of Trade inpector was r equested

to intervene. This was Major

Marindin and his methods marked a great advance since those of Pasley

mentioned elsewhere in this Issue. With nothing resolved, Forman departed

to accompany Marindin on his end-to-end, week-long (and prospectively final)

examination of the West Highland line. MacPhee was sent in pursuit with amended

proposals but returned empty-handed. Though he had found engineer and inspector

at Tyndrum, they were preoccupied by an accident in which the fireman of

a ballast train had been fatally injured. On the evening of Monday, 9 July

the inspection party reached Fort William and that very afternoon

the President of the Board of Trade, facing questions in the House of Commons,

had promised mediation. In consequence, a telegram awaited Marindin at the

Alexandra Hotel he must use his best endeavours to bring town and

railway company to a new accord. Provost Young and town clerk Fraser, with

MacPhee in attendance, presented themselves that night at half past

ten oclock, to request that Forman resume negotiations there

and then. Not unreasonably, the engineer declined.

During Tuesday Marindin examined the entire layout at Fort William. He also

revisited the line along Glen Spean, where the stations at Inverlair, Roy

Bridge and Spean Bridge had received only brief attention the previous day.

On Wednesday he heard both the commissioners submission and Formans

counter-argument. The inspectors verdict, announced on his return to

London, showed careful balance (or skilful fence-sitting?). Without condemning

the pierhead station, he judged the old fort the better site. Acknowledging

that Fort William had been deceived, he proposed to interpret the towns

protection clause generously, in respect of public passage across and alongside

the seawall line. But he also pronounced that a tramway as first intended

could not have been made compatible with the open promenade-cum-carriage

drive which the commissioners still cherished. He would have prescribed thorough

fencing, or imposed restrictions severely limiting public access.

In his own mind, Marindin had resolved not to pass the barely finished West

Highland for traffic before his task was two-thirds done his interim

memorandum to this effect was written at Tyndrum. However, he hinted that

he would be indulgent in everything not absolutely required for safety on

his re-inspection a few weeks later. Though it proved a very near thing,

on Friday, 3 August he declared the line ready. With Fort William and Lochaber

determined to celebrate, the foreshore quarrel was for the moment set aside.

Opening day saw a double celebration in that the West Highland Mallaig Extension

had just secured Parliaments approval though the Treasurys

input had yet to be confirmed. Thus the foreshore dispute would be resumed

in a new context, which also included the collapse and precarious reinstatement

(1894-5) of the Great Glen Agreement. And the terms eventually accepted by

the Fort William commissioners in 1896 would be bound up with the West Highland

Ballachulish Extension, authorised that same year but never to be begun.

These are matters for another article.

| Map: Glasgow & North Western Railway, 1882-3. Note connecting spur across Strathfillan to the Callander & Oban at Tyndrum and the crossing of Loch Leven at the Dog Narrows, not Ballachulish Ferry. Based on J & W Emslie Official Railway Map of Scotland. 1927. | 38 |

| Fort, Fort William in late 19th century: old barracks building converted to houses: retained by NBR but demolished by LNER. | 39 |

| Lucas & Aird pug at the half-demolished fort | 40 |

| Modern view showing how the railway squeezed past the Nevis Distillery, where a gable had to be rebuilt. The site has since been redeveloped | 40 |

| Fort William area, showing authorised line and Roshven extension and deviation and Banavie branch extracted from Ordnance Survey 6-inch Second Edition, Inverness-shire - Mainland Sheet CL 1904. Date revised: 1899 | 41 |

| Seawall and railway c.1900. NBRs Tweeddale Place tenements in centre of view; passageway through wall can be seen to right (coloured image) | 42 |

Grant Cullen. The North British Railway and

the Great War: organisation, efforts, difficulties and cchievements.

44-8

When, shortly after the outbreak of the war in August 1914

and the successful despatch of the first Divisions of the British Expeditionary

Force to France, it became obvious that railways were to play a part of primary

importance in the development of the conflict, that the war, in fact, was

to be a "Railway War". More than four years later British railways had

accomplished, as a result of their activities which had taxed their energies

and resources to the utmost extent, and had exercised a considerable influence

on the movements and achievements of the British forces, if not on the actual

course and outcome of the war itself.

The construction of railways, in time of peace, to serve the purposes of

war, offensive or defensive, was first advocated in Germany in the 1830s,

becoming that countrys policy, although the need for organisation,

directed to the provision for the building, repair, destruction and working

of railways and for the regulation of military traffic in general under war-time

conditions was not fully realised in Europe until after the American Civil

War of 1861-1865. In 1866 Prussia established a Field Railway Section

(Feldeisenbahnabteilung) which was eventually to develop into a comprehensive

scheme of preparation for war by organising every possible phase of military

rail-transport and leaving nothing to chance that could be foreseen and provided

for in advance.

With the eastern part of its system stretching along the shores of the North

Sea from Berwick-upon-Tweed to Aberdeen; with its trunk lines radiating from

Edinburgh to Carlisle, Perth, Stirling, Glasgow, Fort William and Mallaig

and with its direct connection with the further north of Scotland and the

railways of England, through its association with the Highland Railway at

Perth, its partnership with the Great Northern and the North Eastern in the

East Coast Route between London (Kings Cross) and Scotland, its cooperation

with the Midland in respect of the Waverley Route, via Carlisle, Galashiels

and Edinburgh, the North British Railway came into immediate prominence as

one of the vital means of communications in Great Britain for the purposes

of The Great War.

There were, however, various special reasons that arose, which tended still

more to accentuate that fact. It was considered then that it was quite within

the range of possibilities that an invasion of the country by the enemy might

be attempted on the East Coast of Scotland. Hence the NBR was called upon

in the earliest of days to convey to their appointed destinations the troops

to be amassed for defensive purposes along the coast. Many military training

centres were, also, set up within convenient distances of NBR lines, their

location being, no doubt, inspired to a certain extent by the idea of having

more men available in case the enemy should attempt a landing. Much of this

fear of invasion, particularly amongst the general populace, had been driven

in the early 1900s by a series of spy novels, the best known

of which was The Riddle of the Sands by Erskine Childers (Childers

subsequently lost his life in the Irish Civil War in November 1922). As described

in its authors own words, Riddle of the Sands was written as ...

a story with a purpose written from a patriots natural

sense of duty, which predicted war with Germany and called for British

preparedness. The whole genre of invasion novels raised the

publics awareness of the potential threat of Imperial Germany.

Although a belief has grown that the book was responsible for the development

of the naval base at Rosyth, the novel was published in May 1903, two months

after the purchase of the land for the Rosyth naval base was announced in

Parliament (5 March 1903) and some time after secret negotiations for the

purchase. The first Railway Executive Committee was constituted as follows.

Sir Frank Ree (LNWR);

(later Sir) Herbert Walker, London

& South Western; Sir Guy

Granet (Midland); Mr. F. Potter

(Great Western); (later

Sir) A. Kaye Butterworth (North Eastern);

(later Sir) J A F Aspinall (Lancashire and

Yorkshire); Sir Sam Fay (Great

Central); Oliver R. H. Bury (Great

Northern) and Donald A. Matheson

(Caledonian). Matheson was in fact representing the North British Railway,

the Highland Railway and the Great North of Scotland Railway, in addition

to the Caledonian. The North British Railway remained as the Railway

Secretary Company for Scotland. Matheson had held the rank of Major

in the Engineer and Railway Volunteer Staff Corps from July 1900. That the

NBR acquiesced in this appointment was testament to improved relations between

the NBR and The Caley during the early years of the 20th century.

The first Secretary of the Executive Committee, under Sir Frank Ree, was

L W Horne, later Superintendent

of the Line of the LNWR. Sir Frank Ree died suddenly on February 13th 1914

with Herbert Walker being appointed in his place. The Committee adopted for

their headquarters the Westminster offices of the LNWR on Parliament Street,

London and here, prior to July 1914, they had had six meetings.

The peace-time preparations of the Executive Committee further included the

provision of means by which it could rely, in time of war, upon being in

direct communications with the leading centres of railway communications.

At first a system of wireless telegraphy was projected, but this was abandoned

in favour of telephone installation. Under the direction of the Government,

the Post Office authorities supplemented their ordinary London and trunk

line services by providing a system of telephone wires between the Executive

Committees offices in Westminster and all the railway termini in London,

together with the general offices of the Midland Railway in Derby, the North

Eastern at York and the Lancashire and Yorkshire at Manchester. Inasmuch

as each centre of railway administration itself controlled a telephonic system

. This comprehensive system of telephones, which was to play an extremely

important part indeed in the working of the organisation was completed only

the very week before the declaration of war

Sources

Official History of the Great War (Francis Edmonds) Vol. 1, 1923,

originally published by Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence.

Reprinted by Naval and Military Press 2013. KPJ: note not Edmunds as per

article: checked with York University OPAC

British Railways and the Great War (Pratt)

Vol 1, originally published by Selwyn and Blount, Ltd. Available in the

Classic Reprint Series of Forgotten Books. Also available to view

online at https://archive.org/ details/cu31924092566128/page/ n6/mode/2up

An unappreciated field of endeavour: logistics and the British Expeditionary

Force on the Western Front 1914-1918 (Clem Maginnis). Helion: 2018.

Illustrations:

Donald A. Matheson, General Manager of the Caledonian Railway |

45 |

Sir Frank Ree of the LNWR, as portrayed in Vanity Fair |

46 |

Part 2 will be War! State Control Applied Mobilisation covering the full extent of their own lines, the facilities afforded to the Executive Committee for communications with every part of the country were exceptionally great.

[J37 0-6-0 No. 64582 with train of 20 bulks (Leith General

Warehousing grain wagons) near Morningside Road]. Stuart Sellar.

48

Photograph: Caption suggests train may have been en route from Thomas

Bernard's maltings at South Leith to T. & J. Bernard's Brewery next to

Gorgie East station in 1950s. See Issue 141 page

3

Allan Rodgers. The Scotsman vans of the NBR

a follow-up. 49-52

Following publication of previous article on the Scotsman newspaper

vans, which appeared in Journal 139, Study

Group member Jim Hay got in touch. It turns out Jim has a 7mm model of one

of these vans, in NBR livery, originally built many years ago by Sir Eric

Hutchison, who, it will be recalled, wrote the article on the Scotsman

vans which appeared in the November 1945 issue of Model Railway News.

Much of the information I had included on the 1890s six wheeled vans was

based on the information contained in Sir Erics article; so, the existence

of a model built by him was clearly a source of new information about the

livery of these vans as running in NBR days. So much so, that I decided a

follow-up article was required to include amended illustrations of the 1890s

vans showing the NBR livery I now believe they carried, based on scrutiny

of Sir Erics model.

Illustrations (all except on from Model Railway News in colour).

| Photograph of Sir Erics model side and end view. Note vermillion ends and black solebar and ironwork: ends steps are also black, with upper surface in vermillion. | 49 |

| Photograph of Sir Erics model part elevation. Note missing handle on the single door to the left of the ducket clearly this is a dummy door. | 50 |

| Photograph of Sir Erics model close-up of Scotsman scroll. | 50 |

| Elevation drawing of van number 257 as used in Model Railway News article of 1945. | 50 |

| Drawing: of Scotsman van number 251 in NBR livery. Allan Rodgers | 50 |

| Revised drawing of Scotsman van number 257 in NBR livery. Allan Rodgers | 51 |

| Drawing: of Scotsman van number 251 in LNER livery, as LNER No. 3251. Allan Rodgers | 52 |

Stewart Noble Where was Helensburghs first

railway station? 53-8

The short answer is that Helensburgh is where it was first located

in 1858, that is adjacent to the corner of Sinclair Street and East

Princes Street. References to a station in George Street probably relate

to a ticket platform where returning commuters left the train and joined

their horse-draewn transport. A report by Major Marindin in 1892 is used

to justify the permanence of the original terminus station, rather than

assertions made by the author elsewhere.

| Helensburgh, showing station and surrounding area in early 1860s map extracted from Ordnance Survey 25-inch First Edition, Dumbartonshire Sheet XVII.5. Publication date: 1862. Survey date: 1860 | 54 |

| As above but further east, Ordnance Survey 25-inch First Edition, Dumbartonshire Sheet XVII.6. | 54 |

| Original station, viewed from corner of Sinclair Street and East Princes Street, with the municipal buildings in foreground. | 55 |

| Warehouse at 19 George Street | 57 |

Operating the Caledonian

Railway Andrew Boyd reviews a recent two-volume work by Jim

Summers. 59

At first sight the review of a two-volume work about the Caledonian

Railway must surely have no place in a Journal devoted to the NBR, so why

has the Editor been prevailed upon to allow its inclusion? The answer is

that they provide an excellent insight into how a major railway of that era

functioned and was managed and operated. Every railway was different and

each had its own management structures and methods of conducting business.

However they all faced similar challenges and were all subject to the same

statutory and regulatory requirements. They had to co-operate with other,

often competing, companies. They exchanged traffic, complied with Railway

Clearing House accounting and other obligations, managed joint lines and

stations, exercised running powers over the lines of other companies and

had to accommodate the running powers exercised by other companies. Students

of the North British Railway will therefore find here much to interest and

inform them, not least in comparing CR practice with that of other companies.

Such comparisons were not always unfavourable to the NBR. Although written

in an engaging style, the author has applied a professional perspective to

his subject. He is well qualified to do so as in his working life he was

a career railwayman who occupied senior positions within BR management. Apart

from his current role as vice-chairman of the Caledonian Railway Association

and as a railway modeller of some standing, he is also a member of our Group,

well known to many of us. The contents encompass most aspects of managing

and operating the railway. These range from the structure of top management

and the duties of various grades of staff to the classification and loading

of trains, operation of marshalling yards and hazards of shunting; and from

the timetabling and operation of the Royal Train to the running of suburban

and workmans trains and the handling of mail, parcels, goods, mineral

and livestock traffic. Amongst the aspects covered are what the author nicely

describes as getting on with the neighbours; arguments with traders about

demurrage charges; operation of slip carriages; timetable preparation; and

the operation of a selection of principal stations including the joint station

at Perth. He also covers the investigations made into the feasibility of

electrifying the Glasgow Central Low Level lines in the early years of the

last century and Donald Mathesons examination of US practice in relation

to coal wagons and shipment. The latter issue was one of considerable financial

relevance to railways such as the CR (and NBR) that were major coal

carriers.

As with his previously published book on signalling the present volumes are

copiously illustrated.

The comparisons with other companies are particularly useful. In a chapter

on organisation, the author explores the role of Superintendent and his duties.

In 1916 the CR was, as the author puts it, tinkering and beginning

to use the term Superintendent of the Line, while around the same time the

NBR was also considering its own organisation but more fundamentally. Two

posts emerged on the NBR in 1917, namely an Operating Superintendent (Major

Charles H Stemp), and a Commercial Superintendent, evidencing the NBRs

decision to formalise the split between commercial matters and the running

of trains.

No doubt with the eye of a professional railwayman the author discusses the

compilation and layout of the General and Sectional Appendix to the Working

Timetables. The Appendix had become a crucial document for those operating

the railway yet the CRs final issue in 1915 was in his words a

weighty, inconvenient hotchpotch whereas the NBRs approach was

more progressive, not allowing the imminent grouping deflect it from issuing

in 1922 a modern edition of its Appendix. He commends the innovations

introduced by the NB and speculates what the CR might have adopted had it

remained independent. As it was the CR contented itself with issuing in 1921

an unenterprising traditional Supplement

to its hefty Appendix

of 1915.

In his chapter on Control the author notes that despite the challenges faced

by the CR in operating its congested main line over Beattock and in handling

the intense mineral traffic in Lanarkshire, it was the NBR which at Portobello

in 1913 pioneered in Scotland the notion of a control office. Reference to

these instances is not of course to suggest that the author fails to commend

the CR when appropriate nor that he fails to compare the CR favourably with

the practice of other companies when justified but these do illustrate the

objective approach adopted by the author. Amongst the examples of the working

relationships which necessarily arose between the CR and the NBR two instances

may be mentioned. An edited version of an article by David Stirling first

published in the SRPS magazine Blastpipe describes the conflict

between the two companies over the rebuilding by the NBR of the swing bridge

carrying its Stirlingshire Midland Junction railway over the Forth &

Clyde Canal. The CR had to resort to litigation to force the NBRs hand

over this issue but eventually an agreement was reached to enable work to

proceed. While the line was closed for work to be done, extensive diversion

of trains operated by both companies had to take place, often entailing reversals

at Greenhill, Polmont and Grangemouth Junction.

A few years later an unplanned line closure resulted from a vessel colliding

with the CRs Forth Bridge at Alloa in October 1904. The line, used

by the trains of both companies (as the NBR exercised running powers over

it) was closed until June 1905. Co-operation resulted in the institution

of a service of three CR passenger trains each way over the NBR route between

Alloa and Stirling and the conveyance of CR passengers and traffic on two

evening NBR trains each way on the same route. These two volumes are thoroughly

recommended to all those who wish to learn more about how railways were managed

and operated in the days when companies like the NBR and the CR were in

business.

Macmerry Station. 60 (rear cover)

Macmerry had quite a simple layout, but did include a run-round loop

and two sidings (one with a crane), together with a passenger platform long

enough for an engine and a few coaches. The branch on the eastern side of

the station, diverging to the south of the map extract and heading roughly

north-east on the lower right hand part of the extract, was a mineral railway

serving Merryfield, Bald, Dander and Engine Pits to the north of what is

now the A1 road. Extracted from Ordnance Survey 25 inch Map of Haddingtonshire

IX.11. Publication date 1894, revised 1892.

View, taken at Craigentinny, is almost certainly |

|

No. 141 (December 2020) |

From our Archives. 3.

Photograph of employees at St. Margarets pose in front of 4-4-2T

locomotive No. 450 (later LNER Class C16). The only name that is recorded

is that of William Dowie, the fitter on the right. He was the son of a driver,

Sam Dowie. The photograph, from the Hennigan collection,is credited to W

Dowie. Included in the photograph with the relatively youthful employees

are various items including a buffer, a brake block, and on the trestles

to the right what is possibly one of the valve rods with its pistons.

In the right foreground, the barrels probably contain supplies of lubricating

oil.

An apology from the Editor.

3.

Shortly after Journal 140 was published, with the photograph on the

left on page 48, Stuart Sellar contacted us. He had immediately recognised

the picture of the J37 and train, which was taken by him on 13 June 1955

approaching Morningside Road. The train from South Leith was heading for

either Gorgie or Cameron Bridge. He tells us that it is credited to the

Hennigan Collection because he sent Willie anything of North

British interest that he had taken, or older prints that had emerged from

retired railwaymen. He expressed surprise that Willie had not acknowledged

the source. This was not an omission by the late Mr Hennigan it was

an error on the part of your editor, for which he apologises. The Groups

photo archive shows Stuart Sellar to be the photographer and we are happy

to set the record straight

Euan Cameron. The Reid Scott class 4-4-0s.

4-19.

Became LNER classes D29 and D30. At the end of 1908

the NBR Locomotive Committee received designs for new locomotives, including

a new bogie passenger design. It was agreed that six would be ordered initially

from outside contractors. On 28 January 1909 a contract was made with North

British Locomotive Company to supply six four-coupled passenger engines at

a cost of £3,290 each. In the summer of 1910, the Board discussed ordering

more of the engines, and eventually agreed that ten more engines would be

built at Cowlairs. Numbers for these, taken from engines assigned to the

duplicate list, were agreed on 15 June 1911. The same price was stipulated

for the in-house engines as for the contractor-built ones. The engines thus

ordered entered service between September and December of 1911.

Meanwhile, during 1910-11 the Board had already been discussing the possibility

of building engines with superheated boilers. In February 1911 it was resolved

that two Scott class locomotives would be built with superheated boilers.

These were numbers 400 and 363, approved in early 1912, but not built until

the autumn of that year, at a cost of £5,980 (presumably for the pair).

In 1914 approval was given for 15 more superheated Scotts to be built at

a total cost of £45,47. A further five were authorized and built in

1915, and a final five in 1920. The N.B.R. paid royalties on the use of the

Robinson superheater apparatus on condition that no other types were used

on new construction.

The planning and construction of new 4-4-0 locomotives was under discussion

from 1909 to 1920: the 6-ft 6-in wheeled Scotts or the Intermediates and

Glens with 6-ft 0-in wheels. Large numbers of older locomotives were being

withdrawn, and the need for more powerful passenger engines to work trains

with heavier bogie carriages was pressing.

The 1909 Scotts as first built (the 895 Class)

The first saturated Scott engines were, in effect, versions of the

317 4.4.0s of 1903, later L. N. E. R. class D26

namely 4-4-0s with 3-ft 6-in bogie wheels and 6-ft 6-in driving wheels

and 19-in x 26-in cylinders set on a plane inclined upwards from the

driving axles to the smokebox. The cylinders were regulated by outside admission

8-in diameter piston valves on a plane inclined downwards from the driving

axles towards the front, driven directly by Stephensons Link valve

gear which was reversed by a steam reverser just inboard of the mainframes

on the drivers side. All these features were essentially shared between

the 317 and 895 (later D29) classes. The General Arrangement for the 895

class was Cowlairs drawing 3090: with annotation stating it was copied from

NBL drawing 1 of Order L344 (though various notes mentioned minute differences

between the NBL and Cowlairs examples). This drawing is 12748 in the NRMs

series of Oxford Publishing Co. drawings.

The steam reverser was an interesting piece of equipment, though it seems

that the engine crews never settled to it as did enginemen on other railways

where it was more common, such as the Glasgow and South Western or the South

Eastern and Chatham Railways. It comprised a vertically aligned steam cylinder

mounted with a shared piston rod above a cylinder of hydraulic fluid: actuating

the reversing lever opened a bypass valve for the lower chamber, allowing

a piston inside it to move freely, while it also admitted steam to either

the top or the bottom of the steam cylinder, moving an arm aligned with the

bottom of the lifting links of the valve gear down or up. Attached to that

lifting arm was a bearing, with a slender vertical rod attached, which acted

on a bell-crank to transmit the position of the valve gear to an indicator

visible to the crew in the cab. Both the control and indicator rods were

of quite light material.

The most obvious difference from the 317s was the much larger boiler, with

a 5-ft 0-in diameter barrel made up of two butt-jointed plates, pitched 8-ft

2½-in above rail level. This larger boiler also necessitated a wider

cab than had been common before that point, of 6-ft 10-in outside width and

with sidesheets 7-ft 5-in high. The boiler and cab were fundamentally the

same as those on the second series of Intermediates or 331 class (LNER class

D33) which were being built around the same time, except obviously for the

larger splashers on the Scotts

Superheated Scott design of 1912

Nos. 400 and 363, the first Scotts to be built superheated, represented a

departure in front-end design for the NBR. The 20-in x 26-in cylinders were

aligned horizontally with the plane of the axles. Iinside admission 8-in

piston valves were set in parallel to the cylinders but 1-ft 8¼-in above

the centre line. The piston valves were (steam being admitted in the mid-space

between the two ends of the valve, rather than at the outer ends of the valve

chamber) and consequently the action of the Stephensons valve gear

was reversed through rocking shafts attached to the front of the motion plate.

The valve gear used shorter eccentric rods than those on the saturated engines

(4-ft 6-in centres rather than 4-ft 10-in). Unlike all other members of the

class, Nos. 400 and 363 were fitted with the same design of steam reverser

as on the saturated Scotts. Moreover, for some reason these engines retained

their steam reversing gear much longer than the rest. No. 9400 was photographed

still equipped in 1935, and No. 9363 in 1938.

Fitting piston valves above the cylinders required the boiler to be 3½"

higher than on the saturated engines. The superheated locomotives required

more lubrication and had large Wakefield mechanical lubricators fitted on

a pedestal on the right-hand side of the running plate, which derived motion

from a complex set of adjustable levers from the valve gear. No. 400 was

also fitted with a superheater damper on the right-hand side of the smokebox,

but this was soon removed. Both engines had snifting valves in the

smokebox waist: which protruded directly out from the smokebox, whereas on

later examples they were attached to an elbow joint and pointed downwards.

The boilers on 400 and 363 differed in detail from those on later versions

of the class. As built the first two had Schmidt Superheaters with long return

elements, as opposed to the Robinson short loop superheaters used on the

examples built from 1914. The first two boilers also had the smaller design

of Reid dome, as fitted to the 895 class. These and other differences caused

the first two locomotives to be classified D30/1 by the LNER at first, though

subsequent exchanges of boilers between different members of the class made

the part numbers redundant, and they were later abandoned. The official boiler

pressure of the engines built superheated was 165 psi, though it is not clear

whether the lower pressure was retained consistently.

The cabs were slightly wider than those on the 1909 Scotts, at 6-ft 11-in

wide, and the sidesheets were ½-in shorter in height, differences which

would be perpetuated on the very similar Glen class. Notwithstanding these

adjustments, there was insufficient space for the traditional circular spectacle

windows on the front of the cab, so a rectangular window, with part of the

rectangle cut in to accommodate the boiler, was fitted instead.

Production Scotts of 1914-1920

The 25 engines of the main sequence of superheated Scotts were

built in three batches of fifteen, five, and five over a seven-year period,

but as built the locomotives were very similar. Cowlairs General Arrangement

drawing 4289B described them (12765 in the NRMs series of Oxford Publishing

Co. drawings). The basic layout of the locomotives was identical to the first

two, but the production versions had 10-in diameter piston valves, and the

steam reverser was replaced by horizontal screw reversing gear in the cab,

acting on a vertical arm attached to a weighshaft just ahead of the splashers

near the top of the frames. The boilers all had Robinson short-loop superheaters

with 24 flues, and the anti-vacuum valves were of the pepper-pot type attached

to an elbow joint just above the frames on the smokebox. Reids larger

diameter dome was fitted. One divergence from the first two locomotives was

that the main series of Scotts, possibly up to and including No. 498, were

initially fitted with pyrometers, fitted to the right-hand side of the smokebox

just below and to the rear of the chimney, and manifested as a prominent

short pipe protruding upwards, connected to a long narrow tube leading back

to the cab, but were soon removed'

All these locomotives were fitted with both Westinghouse and Vacuum brake

from new. Overall, the Scotts shared in the very robust, solid construction

typical of Reids designs at this period, where nearly every structural

component was made just a little larger and heavier than had been the case

in Holmess time.

Changes to the D29s in service

Older NB locomotives typically underwent rebuilding at 20-25 years old, but

did not happen to the engines built new by W.P. Reid. However, multiple important

alterations were made to the classes under the LNER. Charting the sequence

of these changes is not straightforward: they were not carried out at the

same time, although in the case of the D29 Class they were generally done

in a consistent order. Sometimes two changes were done at the same visit

to the works, though never all three at once. The dates of the following

changes are supplied in the data list at the end of this article.

1. Replacement of the steam reverser with a screw reverse

The steam reversers were marked for removal relatively early on, between

1925 and 1931. A new weighshaft was fitted in more or less the same position

as on the D30 Class, and it was actuated by a reach rod which, unusually,

ran outside the boiler for all its length until it entered a fairing just

in front of the cab, where it was worked by a circular handle on a large

screw thread. When the weighshaft was moved to the top of the frames, the

downward extension of the mainframes which had housed the former weighshaft

bearing was cut away. This reversing arrangement was the same as that used

to modify the D32 and D33 Intermediates, though the larger wheels of the

D29 required the reach rod to be cranked slightly near the front and the

reverser itself to be set approximately 5-in highe

2. Fitting of superheated boilers

This alteration probably made the most dramatic difference to the performance,

as well as the appearance, of the D29s. All were superheated between 1925

and 1936. A new General Arrangement was prepared, Cowlairs No. 5385B, 12810

in the NRM series of Oxford Publishing Co. drawings. The drawing is however

a trap for the unwary, in that it shows the superheated engines still with

steam reversers, a condition in which none of the D29s ever ran. The new

boilers were effectively the same as those on the D30s, and indeed boilers

were regularly interchanged, not only between the two classes of Scotts,

but also with the superheated Intermediates and Glens. New smokeboxes were

fitted, which extended the smokebox interior lengthwise by 7-in. The chimneys

were moved forward by 5-in to accommodate the superheater headers at the

rear of the smokebox. Generally, the D29s continued to be rated for 190 psi

boiler pressure after superheating (as was also the case with the Intermediates)

making them theoretically more powerf ul than their more modern D30 counterparts

even though the latter had an extra inch on the cylinder diameter. It would

seem that, having had a somewhat doubtful reputation as saturated engines,

the D29/2s were regarded as good engines once superheated.

3. Replacement of the Westinghouse Brake with Steam/Vacuum brake

The removal of Westinghouse brake equipment was the last change to be made,

generally in the mid-1930s in keeping with LNER policy for all but those