|

Cuthbert Hamilton Ellis

Back to Index page

|

Note: this web-page is beginning to show its age and should be revised: it began as the manuscript for a retrospective review of The trains we loved and has grown into something larger. In part it suffers in its greater manifestation from the compiler of the web-page not having ready access to a complete collection of Ellis's printed works. Kevin Jones. 10-12-2010. The biography of the subject is scattered all over the place and an important bequest and his life as a spy remain buried. In an atempt to improve matters some of Hamilton Ellis's preliminary material, such as his acknowledgements, has been scanned and added to this web-page as this shows how he worked, whom he lent against, and casts further light on a period long past when access to information was very different.

[Cuthbert] Hamilton Ellis's output is fascinating on a great many levels. He could certainly write: there is widespread agreement on that. He appears to have been an accurate observer of a railway system which has long since departed, namely that of the Edwardian period, which many regard as being the zenith of the railway age. He was also an artist, whom George Dow, appears to have admired in terms of accuracy. He even wrote a small amount of fiction about railways mainly for boys, which I have extremely vague memories of reading when about ten or eleven, and at least one work of adult fiction. Ottley noted that Dandy Hartis a novel, interwoven with many facts, incidents and scenes from railway history in Southern England during the period 1830-60. The story is centred mainly on the LB&SCR, but the GWR and L&SWR are also featured. These works were published by firms, such as Gollancz and Oxford University Press which enjoy a considerable reputation for literary excellence.

Simmons in his own brief sketch (Oxford Companion) noted that Ellis was born on 29 June 1909 and died in 1987. He was educated, like Simmons, at Westminster School, attendance at which probably involved greater contact with railways than was the case with most public schools. Simmons notes a brief attendance at Oxford, and that he "became one of the most prolific of all British writers on railways; Ottley lists 36 of his books, the first of them published when he was 21. He was interested above all in steam locomotives, which he observed affectionately in Britain, Holland, Germany, and Sweden. And yet perhaps his most notable book was Railway Carriages in the British Isles, 1830-1914 (1965). He became highly knowledgeable, and much of his knowledge was interesting and lay out of the way; but unfortunately he scarcely ever gave any references to support his stories, so nobody can judge how far they are reliable. His writing is always lively, and picturesque in the literal sense of that word, because he was a painter too. His largest work, British Railway History (2 vols., 1954-9), despite some errors, was a brave attempt to provide something badly needed (and still wanted): a general account of the whole subject. But he worked uneasily on a large scale, and the book does not make a satisfactory, continuously informative whole".

Carter overplays Ellis's contribution to a railway enthusiast publishing explosion, but does emphasise Philip Unwin's contribution to the quality of his publications.

Neil T. Sinclair (Backtrack, 2015, 29, 462) not only commented on the spurious livery which clothed No. 103, but noted that he had spoken to Miss Mary Beale Jones, daughter of David Jones, had completed the F. Moore painting of Clan Mackinnon and made scurrilous remarks about his fellow railway authors, notably Cecil J. Allen: "a rather pious character who would blush from the neck upwards at the mention of a lavatory brush"

Although the bulk of Hamilton Ellis's output was published long ago, it is relatively simple to acquire many of his books in second hand bookshops, at remarkably little cost, or see copies in libraries. A few were published as paperbacks, but these suffer from inferior paper, binding and presentation in general, although some of his case-bound books also lack the quality which was achieved even during the dark years which followed World War 2. A full examination of his work may gradually emerge and this introduction will attempt to be no more than a brief sketch of both the writer and the artist. The typical book tended to combine both skills, although some works consist mainly of illustrations (not all of which may be in colour), and some books are primarily textual. Most are "locomotive and rolling stock histories". The output includes a not entirely satisfactory, but mainly excellently written, two volume History of railways in Britain (see later), and an excellent history of the railway carriage.

"Recently" the compiler of this web page has been informed about the bequest of his final estate (some paintings, photographic negatives, railway books, railway memorabalia and "records", whether these were as in Transacord, or as in manuscript, is not clear, and colour transparencies of his paintings) in 1991 to the National Railway Museum. The cost of the transfer was to be covered by the residue from his widow's estate. It is assumed that this collection will have been catalogued (the pictures may be in the NRM "Search Engine")..

The BBC History Magazine, 2007, 8, (3), p.10 Unwitting saboteur contains an article by Graham Macklin about Hamilton Ellis's WW2 activities in Switzerland. This activity is covered in newly released documents held by The National Archive which show that his visit to Switzerland in 1940 had been orchestrated by the D section of MI6 under Richard Strauss whilst he was working for Modern Transport. The aim was to develop saboteurs who would disrupt traffic ascross Switzerland from reaching Germany. The article suggests that Hamilton Ellis was unaware of the true nature of his work, but this seems unlikely, and the article alleges that he failed to make contact with his handlers. As noted below he made an innovative exit from Switzerland after the fall of France.

For the present it is appropriate to concentrate mainly on one of his best works: namely, The Trains We Loved. The title completely encapsulates the author's abundant joy in his subject. Chapter One opens with "surely it was always summer when we made our first railway journeys!" On the same page he announces that everyone has his favourite railway and his was that "magical South Western"; "Great was the beauty of the annual pilgrimage into Wessex". Ottley, the great railway bilbliographer, noted that it was this book which instigated his own fascination with railway literature.

Ellis made much play on the chaos of the old Waterloo station which brings into question the authenticity of his observations. He was not born until 1909, but he always gives the impression, whether through his prose or through his paintings, that he had an intimate knowledge of the Edwardian railway. He was aged two when that specific era closed. In reality many of his early memories must be of railways during the First World War and their muted revival thereafter. In reality he must have been more aware of Great Eastern and South Eastern grey than their respective blue and green. This observation is based upon my [KPJ] own birth in 1935: I have no memory of "pre-war" railways other than those tantalising glimpses of what remained, such as the red and cream Newcastle electrics which mysteriously changed to two-tone blue, and the similar chameleon antics of the LMS streamlined Pacifics.

This is not to imply that Hamilton Ellis was fraudulent. By the age of six he would have gathered a vivid impression of what was to be lost. Unfortunately, I was too young at the outbreak of World War II to have remembered anything of the railways, although for a long time I cherished memories of bananas, clotted cream, and wafer biscuits, and much of a Cornish holiday spent in Newquay in June 1939! Although my father's diaries make reference to travel on the 9.30 from Paddington, that journey has been completely erased from memory, although other aspects of that holiday remain fresh, even down to the colour of the rowing boats used to cross the Gannel at high tide. Another factor which needs to be considered is that Hamilton Ellis perceived the world from an upper middle class stance and presumably normally travelled first class and made use of the restaurant and sleeping facilities when provided.

As noted, Hamilton Ellis was both a writer and a painter. George Dow was responsible for Hamilton Ellis's series of railway carriage panels based upon his paintings, which appeared mainly on London Midland Region rolling stock in the 1950s. According to KPJ's father, Dow considered these paintings to be highly accurate impressions of the locomotives and carriages. My personal view on the carriage panels was that they were rather too gaudy and contrasted strongly with the squalor within the typical compartment of the 1950s. The use of similar material in books is another matter, where it must be considered as part of a greater whole. As a typical Ellisian diversion, KPJ's father knew Ellis well enough to receive Christmas cards from the writer/artist, and it was almost certainly Ellis that inspired a lifelong pang for the joys of "independent means" in those fortunate enough to possess them thus sparing him the rigours of life on the LNER treadmill.

The painting of railway subjects deserves its own web page; for the present it is sufficient to observe that Turner, Camille Pissaro, and Frith contributed impressive paintings based on railway subjects, whilst other artists, notably the French impressionists and the Camden School, portrayed railway subjects frequently. Most "railway artists", with the possible exceptions of Terence Cuneo and David Shepherd, fail to be "great artists" in much the same way that most railway literature is not great literature. This quality, or more correctly its lack, is most evident in the scenes in which Ellis's paintings are set.

Unfortunately, Hamilton Ellis could not resist inserting onlookers into his paintings: to state that these bystanders are wooden is an understatement. Footplate crews mimic the statuesque stances of early photographs. The landscapes tend to be excessively colourful. In a painting4 of a Caledonian Pullman observation car in the Pass of Brander the artist could not desist from brightening up the dramatic slopes above the train with a rowan tree covered with berries, which in the reproduction look more like exotic oranges ready for harvesting. Smoke and steam are further weak features (the former is a key quality in many railway paintings, notably Turner's Rain, Steam and Speed which reflected a scene on the early Great Western, and clearly influenced the Impressionists, notably Pissaro and Claude Monet). A further problem is that Ellis's trains are always in pristine condition: from a personal standpoint I would have preferred the locomotives and rolling stock to be painted as still lives with bland backgrounds to suitably contrast with the main subject.

In The Trains We Loved the eight coloured plates demonstrate both strengths and weaknesses. There is an excellent still life of a Stirling 0-4-2 behind a Holden 2-4-0 in Cambridge Station spoiled only by an over-prominent milk churn, a dramatic exit from Twerton Tunnel by a broad gauge express, Cardean climbing Beattock during a Hollywood Technicolor sunset, an excellent study of an NBR 2-4-0 at Cowlairs, and a Craven 2-2-2 in Stroudley yellow with three of the Wooden Tops looking on, one of whom sports a Meerschaum pipe. Mrs WT is carrying a spaniel and a parasol. For those used to even model locomotives having a dusting of "soot" it needs to be stressed that the engine crew have polished their locomotives prior to their inspection by the artist! The remaining paintings were of a Johnson single, an Adams LSWR 4-4-0 alongside a Midland & South Western 4-4-0 at Andover, and a Midland Great Western train in the depths of Connemara. The plates in this volume were well-printed on good quality paper.

According to Ellis, and there was scant contradictory evidence at the time it was written (but see also Webb page), Webb was : "a cold, harsh, lonely man considering no ideas but his own, fecund in his original inventiveness, instant as cordite to take offence, intolerant of his subordinates and icily munificent in the great causes of Victorian charity." On the other hand, "Roger Fry, [was] yearning as a boy after beauty and colour in a sepia-toned Quaker household, [who] gazed on the poppies in his father's North London garden, dreamed about locomotives, and told himself that somewhere, some-when, he would see a pure red engine." In many respects Hamilton Ellis was sometimes more successful at painting the overall scene in words rather than with a brush, whatsoever the merits of his record of locomotives on canvas. Although in fairness it must be emphasised that Ellis does enable the viewer to contemplate the colourful railway scene which long predated Dufaycolor, let alone Kodachrome. Rutherford (Backtrack, 16, 635) considered that Ellis had embroidered the truth concerning Webb.

Observing that the decrepit Bishops Castle Railway was near the romantic Stokesay Castle, Ellis recorded: "and just as Stokesay Castle showed you English domestic architecture, complete with all the modern conveniences of the thirteenth century, mellowed and untouched by the hand of war, so did the Bishops Castle Railway, opened in 1866, preserve British railway practice of the industrial middle ages, likewise overgrown and embowered in the country it had sought to serve."

Hamilton Ellis belonged to that section of the British class system, shared by Lucinda Lambton, which can eulogize about lavatories without becoming offensive. Having noted that the provision of lavatories was becoming more common on British express trains at the end of the nineteenth century, he castigated some practices. "Some companies, notably the Cambrian, Caledonian and North British, were much concerned to ensure that the new lavatory carriages seated the same number of passengers per compartment as their predecessors. So the lavatory doors were padded, and hinged seats were placed in front of them. For sensitive people, especially ladies, it was a horrifying arrangement." On the first Great Western corridor trains decorum was maintained as "Men's and women's lavatories were separate, at opposite ends of the carriages. Side corridors were used except for the smoking compartments, which had open passageways with cross seats on each side, as in a diner."

We conclude with Ellis's portrayal of the Skye line: "Released from the close embrace of the glen, the train is careering joyously along the shores of Loch Carron. Above it on one side, the rocks rise precipitously; there is just room for the railway between their foot and the golden brown sea-wrack. At every other twist of the line, your engine flashes into view, her side rods bravely pounding."

Copies of Ellis's The Trains We Loved may be available from: amazon.com.

The Beauty of Railways is a very different book: it is an essay which argues that railways are comparable with other human endeavours, such as cathedrals (author's example), in adding to the landscape and then takes 128 plates to reinforce this argument. Most of these are based on photographs, but some are of paintings, his own, and the work of others, including a Monet. All are in black and white, which is highly acceptable for most of the photographic material, but now looks dated for the paintings. It is hoped that the following extract captures something of his extended philosophy (which appropriately for an artist) demands the illustrations to fully appreciate its force.

There are the Inner Isles from Morar on a clear summer morning or at sundown; there is Wales across the Bristol Channel from above Mortehoe ; there is Salzburg from the Kapuzinerberg; there is Assisi from Perugia, just after sundown; there is London from Adelphi Terrace and, also in London, there is the view down to Clapham Junction from the Battersea Flyover, on a winter evening after rain. Millions see this, but without seeing it. No picture post-cards of it have been published, no guide-books mention it, yet it is one of the world's great views.

Splendidly sweep the great shining tracks to the South and West, weirdly reflecting the colour-light signals. Electric trains rush through and about it, all golden; the rarer steam train rears her smoke column against the afterglow and defiantly waves her fire-plume at the coming night. There is that in the wet, shining rails that nothing else has in the man-made world. It is a transient lovely view, which a few people will remember once the smoke of old steam has blown away from the predominantly electric scene. It is part of the intense beauty of the railway, and a part which could be only during a state of mechanical transition. ...

There are innumerable beautiful things in the world. Again one thinks of those one has seen-something made by Cellini; something painted by one of the Van de Veldes, and a kindred thing in reallife-a great clipper, one of the last of her race, off Gothland, under full sail for Finland. One thinks of the gardens of the Villa d 'Este at Tivoli; there are entire small towns like Lavenham in Suffolk, San Gimignano in Tuscany and Soest in Westphalia ; there are the English and French Gothic cathedrals. One of the most beautiful things, and again a more transient one, is and has been the steam railway. It came in a world where business was ready for development but society was unschooled in visible change. That is why so many who might have appreciated it have been blinded by inspired dislike. In the last century it was to Ruskin the most hideous imposition the world had yet borne, and Ruskin was arbiter of taste to a hundred thousand who were not sure what they really liked. Railway beauty was incidental, not studied. It was functional, and the most functional parts of it were the locomotives and the rails on which they ran. Railway buildings inherited much from classical and, later, Gothic architecture; railway vehicles at their best epitomized a coach-building tradition which had grown up side by side with Georgian classicism. But the locomotive, the rail, and the earthworks across country were original, and a taste for them had, in many, to be acquired. For indeed, an entirely new railway must have been a shocking thing, with its gashes and scars of raw earth and new masonry .Only, as it grew into the country , and as people grew used to it, could a greater number see the splendour of its sweeping lines, see the strength its levels and its curvature gave to a rolling valley. Viaducts, perhaps, were the first features to excite artists, and in them there was a tradition going back to the Romans. The railway, as a railway, was more of an acquired taste. In your editor's opinion, the railway adorns Glenfinnan while the motor road, fine of its kind and time as it is, ruins Glencoe. He will die with that opinion, though the chances are that the opinion will not die with him.

Railway World (1987, Sept) published an excellent obituary:

Hamilton Ellis — an appreciation

One has to say that in military uniform Cuthbert Hamilton Ellis, who died on 29 June, was hardly a striking figure and it was in that garb that he was first encountered. He was on leave and was pursuing researches at our local public library which possessed among other things a remarkably complete collection of the Illustrated London News. It was only later that one came to realise the degree to which the word research was integral with all the work that Hamilton Ellis undertook whether it was for technical pieces, for paintings or, if it comes to that, for the five romances which he wrote and which have never received the appreciation which they merited. He was writing these while he was aiding the late Charles Klapper and myself in the weekly production of Modern Transport and it must be said that it was not easy in wartime conditions to achieve this comprehensively. Ellis had an extensive knowledge on transport matters generally, but we were a little startled when he accompanied the announcement of the British jet engine with an editorial piece on dragonfly larva which was quoted widely in the press and on the wireless.

He had a knack of finding the less usual aspects of subjects and 19th Century Railway Carriages, which he produced originally as a series of Modern Transport articles, was — and is — a classic on a rarely treated aspect of railway operation, embellished by some salty comments on features such as sanitation. After the war came a whole series of historical books such as the two-volume British Railway History which he described determinedly as 'an outline'. Perhaps it was, but it typified a different approach to the subject with more attention to the social surroundings and the personalities involved. These examples set a fashion and can be said to have influenced the treatment of railway history today. As a colleague one always found him supportive. He took part in a press flight in the Short Shetland from the Medway when tight turns were made round Rochester Castle and one heard that Cuthie was as unperturbed as when we were standing together in the corridor of a London-bound train one morning when it was attacked by a German aircraft just south of Polhill Tunnel. He had spent some time in Germany after Oxford and occupied much of our journey through the tunnel conjuring up choice remarks to direct at the hostile pilot. Unlike his classic description in Modern Transport of his escape from Switzerland at the time of the fall of France with the aid of a bicycle and the Belfort fire brigade, I do not think he published his tunnel musings.

John F. Parke

Ottley who always considered that the bibliographer should stand apart from the literature stated in the preface to the second supplement to his Bibliography: "His [Hamilton Ellis's] railway books (over thirty in all) provided highly informative and enjoyable reading for anyone with an armchair fondness for railways.

Books

The beauty of old trains. London. Allen

& Unwin, 1952. 147pp. + 8 col.plates

The colour plates include some of the artist's best work.

The beauty of railways. London: Max Parrish,

1960. 128pp.

British railway history: an outline from the

accession of William IV to the Nationalisation of railways. London:

Allen & Unwin, 1954/1959. 2 volumes

Hamilton Ellis was an extremely modest author and he clearly stated

that his two volume history was not intended to be a "reference book" [his

words] and that "broad history is the present aim". Unfortunately, even as

a broad history the work is something of a curate's egg and the better parts

are where the author had an intimate knowledge of the subject or he treats

the subject on a grand scale. An instance of this last is the Watkin versus

Forbes feud, notably of the South Eastern and London, Chatham & Dover

respectively where Ellis writes in the manner of Anglo-Spanish relations

during the Tudors.

The main problem with the broad brush approach is that certain key topics

tend either to be forgotten or trivialized. There was an interesting spate

of railway construction in the 1890s and 1900s as typified by the GWR new

lines. Although Ellis was an artist he failed to observe that these lines

were distinctive in their civil engineering due to the invention of the steam

shovel or steam navvy, and share much in common with the arterial roads of

the 1920s, and even with the early motorways. More comment might have been

made on the increasing use of concrete in these later railways, although

the Cockfosters extension used brick viaducts, as did the uncompleted Northern

line extension to Bushey Heath. The blue brick viaduct of the Great Western

mainline to Birmingham forms one of the few visually exciting features on

the western segment of the dreary M25.

Ellis' discursive style is in many of his works one of the happiest

features, but in these more serious tomes it becomes annoying and leads to

some key topics like railway electrification being treated in a fragmentary

way.The railway mania appeals to Ellis' imagination yet he is incapable of

conveying the serious and lasting consequences of Britain's partly unplanned

approach to railways. Nonetheless, the market for a good general history

of the development of railways in Britain remains open, and until that

masterpiece is written Ellis' work will have to suffice: at least most of

it is readable.

Contemporary review:

Locomotive Mag., 1955,

61, 84 points to the many failings and some of its strengths

Dyos and Aldcroft (British transport

p. 413) put the boot in: "inclined to melodrama and

facetiousness and is singularly weak on economic factors, but is packed,

all the same, with information that is hard to come by in any other form:

one drawback to using it is its poor index

Specific errors

Robbins (Trans. Newcomen

Soc., 56, p.50 (Ref. 12)) noted that Ellis was incorrect to

attribute serious errors in Edge Hill Tunnel to Thomas Longridge

Gooch

British trains of yesteryear.

Ian Allan. 126pp.

Reviewed (third impression) B.K.C. in

Rly Wld, 1975, 36,

170. Ottley 7878: 288 photographs.

Carriages in the British Isles, from 1830 to

1914. London: Allen & Unwin, 1965.

A wonderful book.

Dandy Hart. London: Victor Gollancz, 1947.

466 pp.

Ottley 7546: novel interwoven with many facts, incidents and scenes

from railway history in South East England during 1830-1860; set mainly on

LB&SCR, but LSWR and GWR also featured

The development of railway engineering.

Chapter 15. of Singer Vol. 5, pp.

322-49. Inevitably highly compressed. The topics covered and diagrams employed

are of interest (and may reflect what Ellis had to hand at the time): Figure

164 (the numbers cover the whole Volume!): Drummond's marine-type big end

as used in Scotland and on LSWR; Figure 165: gab motion; Figure 166: section

through Drummond 4-4-0T for NBR. The switch from coke to coal burning in

locomotive fireboxes is mentioned. There is a diagram and note which mentions

that Peter Bruff invented the fish-plate. Figure 171 features Adams' bogie

with rubber springs which was first employed on NLR 4-4-0Ts. Figure 173 von

Borries compound (there is quite a long section on compounding). Figure 174

Joy's radial valve gear. Figure 176 ccross section of Webb three-cylinder

compound of 1884. With so material on Webb there is naturally a section on

braking systems. Cites Spooner's Narrow gauge railways (1879)...

The Engineer-Corporal. A story of the American civil

war, etc. London: Oxford University Press, 1940. 224pp.

A novel for boys which KPJ read borrowed from the Charlton branch

of Greenwich Public Library. Reviewed

in Locomotive Mag., 1941,

47, 224

The engines that passed. London Allen

& Unwin, 1968. 133pp.

Four coloured plates, many cartoons (as term is used by illustrators)

and vignettes.

The Flying Scotsman, 1862 to 1962: portait of

a train. London, Allen & Unwin, 1962. 47pp.

Ottley 6255

Four main lines. London: Allen &

Unwin, 1950. 225pp.

West Coast, East Coast, Great Western and LSWR. Includes plate (facing

page 77) of North British Railway Crampton painted in tartan livery.

Highland engines and their work. London:

Locomotive Publishing Co., 1930. 117 pp. including 28 plates + front. 46

illus. (incl. 5 line drawings.)

K.R.M. Cameron published a long corrigenda:

Loco. Rly Carr. Wagon Rev.,

1930, 36, 358-9.

The locomotive builders: a short history of the

steam locomotive industry in Great Britain down to 1960.

NRM E17/43L: available from 2008 (manuscript)

The London, Brighton and South Coast

Railway; a mechanical history of the London & Brighton,

the London & Croydon, and the London, Brighton and South Coast Railways

from 1839 to 1922. London Ian Allan, 1960. 271pp. + plates.

The Personal Introduction notes his friendship with Gibbs-Smith whilst

they were at Westminster School, and with Ian C. Allen who was to become

noted for his photographs of railways in East Anglia. It is also acknowledges

the assistance provided by John Pelham Maitland for locomotive history, to

Thomas Spooner Lacselles for signalling, and to R.C. Riley and H.M. Magwick

for proof reading.

Pp. 142-3: Ellis at his very best: More startling alterations were made to

Edward Blount, which was fitted in 1908 with Hammond's patent apparatus

for directing preheated air to the firebox, the air entering a set of tubes

in two drum-like pockets on each side of the upper part of the smokebox,

where it was supposed to be warmed by the smokebox gases. It was a horrid

sight if one did not, alternatively, think it funny, and reminiscent of Aunt

Amy about to enter the sea at Brighton with a pair of water-wings.

London, Midland & Scottish Railway

in retrospect. London: Ian Allan, 1970. 224pp.

Ottley 12270: Rutherford

(Backtrack, 20, 552)

is highly dismissive of the 8 page appendix on the NCC. Sometimes provides

almost unique insights. Very anti-Stamp; much based on Author's time with

Modern Transport. One has the feeling that he did not like the LMS,

possibly because of a lack of hospitality by the Company:

see his jaundiced view of the Liverpool

& Manchester Centenary celebrations.

The lore of steam. London: Hamlyn, 1984.

Available as a rather austere paperback or as a "luxury book".

International in scope and originaally published in Gothernburg. In the paperback

edition few of the illustrations are by the "author"

The Midland Railway. London, Ian Allan,

1953. viii, 192 pp. + col. front. + 35 plates (incl. 1 col. & 1 folding).

90 illus., diagr. (s. el.), 2 tables, map. Bibliog. (footnote references)

Acknowledges assistance provided by George Dow, and by J.E. Kite.

On page vi there is an extract from John Betjeman's poem which begines: Rumbling

under blackened girders, Midland bound for Cricklewood,/Puffed its sulphur

to the sunset where that Land of Laundries stood/Rumble under, train and

tram, alternate go,...Reviewed

by W.H. Bett in Rly Wld., 1954, 15, (168) vi

Nineteenth century railway carriages in

the British Isles—from the eighteen-thirties to the

nineteen-hundreds. London: Modern Transport, 1949. 176pp.

Regarded as his best book: cites sources within text

The North British Railway. London: Ian

Allan, 1955. 232pp. incl. plates.

In some respects usurped by John

Thomas's North British, but Thomas leaves some large gaps, especially

in the locomotive history. See also Author's Personal

Introduction which tells us more about him, rather than about that mean

and impoverished railway. See also his acknowledgements.

There was a second edition, but this lacked the colour plates

Picture history of railways.

Hulton Press, 1956.

Ottley 132: 408 illustrations plus 18pp of text. Cited by Perer Swift

in Backtrack, 2004, 18,

636. Kevin clearly failed to see this title.

Pictorial Encyclopedia of Railways.

London: Hamyl, 1968. 591pp.

An eccentric compilation, compiled with an eye on an International

market, but does include the artist's depiction of the scarlet Greater

Bitain. (fp. 96).

Rails across the Ranges, etc. London: Oxford University

Press, 1941. 254pp.

Railway art; edited by Susan Hyman. London:

Ash & Grant. 1977. 144pp.

This is an important serious book on a subject which has been lightly

sketched elsewhere (notably by that weird butterfly Simmons) and where there

have since been some important contributions by others (one of which has

still to be seen through inhabiting the bibliographical tundra of Norfolk).

Several extracts and a commentary are considered

below.

Rapidly round the bend. A short review of railway transport,

from the time of Abraham; written and illustrated by C. H. Ellis.

London: Max Parrish. [1959] 120pp.

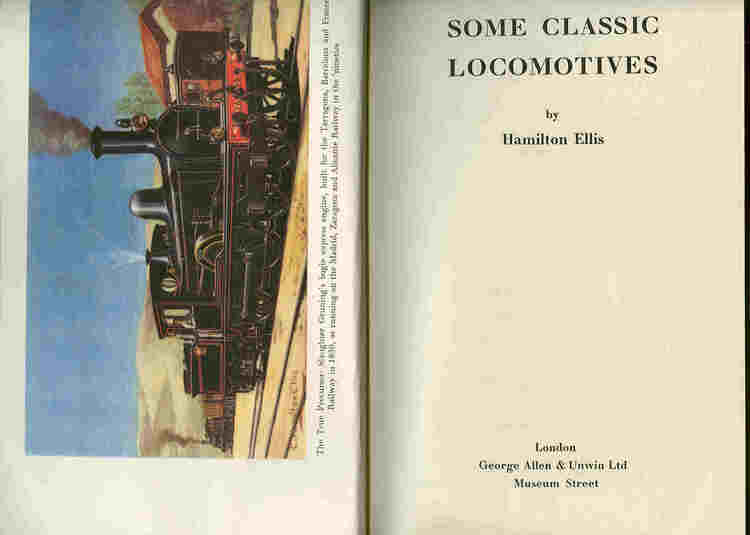

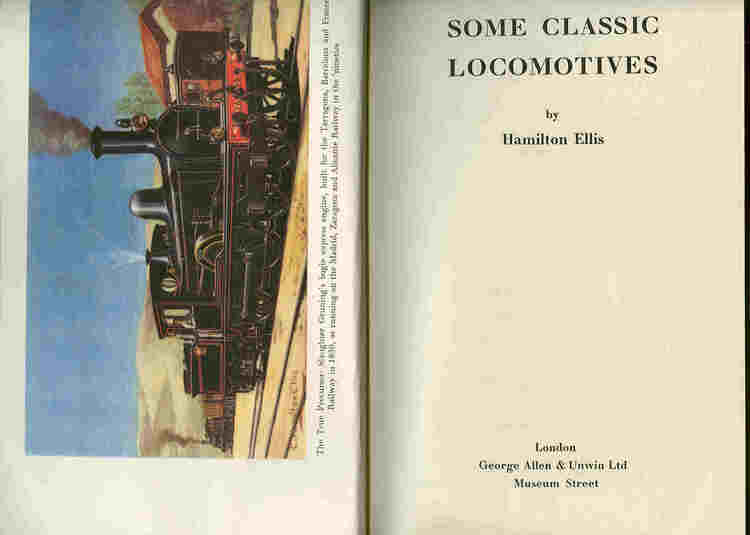

Some classic locomotives. London:

George Allen & Unwin, 1949. 175pp.

Considers designs which the Author considered to be influential: Crampton,

Allan's Crewe type (most commentators would now consider that undue emphasis

was given to Allan), the Beatties; the Metropolitan type; Old English (the

2-4-0); Pat Stirling's masterpiece (4-2-2); Stroudley's D tank and its

descendants; Georges, Directors and many others; Atlantic;

4-6-0 type; the Smith-Deeley compound; the Beyer Garratt.

Page 119: "One night in 1935 I was on one of the platforms of King's

Cross, having just got out of the Silver Jubilee streamlined train after

its breathless press run. It was an excited crowd on that platform; we had

been travelling faster than ever before in a steam train, during that afternoon;

humming along at well over a hundred miles an hour for many miles at, a stretch

had become almost a familiar sensation. Passengers and spectators were surging

round Gresley's Silver Link, which to unused eyes looked faintly like

a small airship under the dim station roof, and her designer, looking very

large and benevolent, was up on the footplate with the enginemen while cameramen

let off flashlights in their faces." Reviewed in

Loco. Carr. Wagon Rev., 1949,

55, 192

Extract in Clouds of

steam

The South Western Railway: its mechanical

history and background, 1838-1922.. London: Allen Unwin,

1956. 256pp. + plates

One of his best books which in parts is almost as beautiful as Betjeman

when arriving in Cornwall on the old South Western mainline which was as

different as the meandering A39 is from the motorway-like A30.

See also his acknowledgements

The splendour of steam.

London: Allen & Unwin, 1965. 132pp.

Landscape format. Sixteen colour plates and 43 cartoons (brush drawings).

Overall the plates make a great impression, although one or two (notably

Plate II Duchess of Sutherland) suffer from technical faults (in this

case the perspective of the smokebox is incorrect) and some include lead

soldiers on the footplate and very wooden figures. The essays which accompany

the illustrations (of both types) are Ellis texts of the highest

order.

The trains we loved. London:

Allen & Unwin, 1947. 196pp.

"Surely it ewas always summer when we made our first railway journeys!":

thus opens Chapter One. The seven colour plates plus the colour frontispiece

are all printed on one side and are based on the Author's paintings. The

text is beautifully printed by John Dickens & Co. of Northampton. (There

is also a Pan Books paperback edition with new plates (printed

on both sides, but well reproduced for the time): it is reviewed by Basil

K. Cooper in Railway World,

1972, 33, 38

Twenty locomotive Men. London:

Ian Allan, 1958. 214pp. including plates.

This was based on a seriies of articles published in the Locomotive

Magazine over several years; not all of which were reproduced in the

book: those excluded are listed below. A further

complication is that the indexes to the Magazine list F.C. Hambleton articles

under "Famous locomotive engineers" (Alexander Allan and John Ramsbottom

are examples from Volume 47)

Contents:

Introduction;

I William Bridges Adams, 1797-1872 (Famous locomotive engineers: Part 21.

Locomotive Mag., 1943, 49,

80);

II Joseph Hamilton Beattie, 1804-1871; (Famous locomotive engineers: Part

19). Locomotive Mag., 1941,

47, 80);

III John Chester Craven, 1813-1887 (Famous locomotive engineers: Part 16)

Loco. Rly Carr. Wagon Rev., 1940,

46, 199;

IV Robert Sinclair, 1816-1897 originally published as Famous locomotive

engineers: Part 8 Locomotive Mag.,

1938, 44, 383;

Sir Daniel Gooch, 1816-1889 , Bart, originally published as Famous locomotive

engineers: Part XVII. Locomotiive

Mag., 1940, 46, 303

VI Thomas Russell Crampton, 1816-1888; Part XV.

Locomotiive Mag., 1940, 46,

67

VII Archibald Sturrock, 1816-1909 originally published as Famous locomotive

engineers: Part

IV Locomotive Mag.,

1938, 44, 93;

VIII Patrick Stirling, 1820-1895 originally published as Famous locomotive

engineers: Part VII. Locomotive

Mag., 1938, 44, 306

IX William Adams originally published as Famous locomotive engineers: Part

IX Locomotive Mag., 1939,

45, 51;,

X Charles Reboul Sacré, 1831-1889;

XI Samuel Waite Johnson, 1831-1912 originally published as Famous locomotive

engineers Part 13 in Locomotive

Mag., 1939, 45, 313-18;

XII William Stroudley, 1833-1889 originally published as Famous locomotive

engineers Part I in Locomotive Mag.,

1937, 43, 149

XIII David Jones, 1834-1906 originally published as Famous locomotive engineers

Part II in Locomotive Mag.,

1937, 43, 253

XIV Francis William Webb, 1835-1906 Part XI

Loco. Rly Carr. Wagon Rev., 1939,

45, 179-82. ;

XV Thomas William Worsdell, 1838-1916; originally published as Famous locomotive

engineers: Part X: Loco. Rly Carr.

Wagon Rev., 1939, 45, 115-17.

XVI Dugald Drummond, 1840-1912; originally published as Famous locomotive

engineers: Part V: Loco. Rly

Carr. Wagon Rev., 1938, 44, 192-6.

XVII William Dean, 1840-1905 originally published as Famous locomotive engineers:

Part XX!! Loco. Rly Carr. Wagon

Rev., 1945, 51, 180-5;

XVIII James Manson, 1846-1935 originally published as Famous locomotive engineers

Part XIX in Loco. Rly Carr. Wagon

Rev., 1941, 47, 126-31;

XIX Sir John Aspinall, 1851-1937;

XX George Jackson Churchward, 1857-1933.

Bibliography.

Rutherford is highly critical of Ellis's assessment of F.W. Webb in this

study. Sadly, Ellis must be one of those historical figures whose authenticity

must be brought into question, although his writing, and even his painting,

remain models to which the majority never emulate.

Excluded from book

Charles Beyer: Famous locomotive engineers: Part 4.

Locomotive Mag., 1937, 43,

351

Joy is covered in Famous locomotive engineers: Part 14.

Loco. Rly Carr. Wagon Rev., 1940,

46, 153-6

Alexander McDonnell is covered in Famous locomotive engineers. Part 12.

Loco. Rly Carr. Wagon Rev., 1939,

45, 257-61.

Fletcher (excluded from Twenty) is in

Locomotive Mag, 1938, 44,

274.

James Holden (excuded from Twenty was number XX in the

Locomotive Magazine series (1942,

48, 110).

Book reviewed in Locomotive Mag.,

1958, 64, 220.

Who wrecked the Mail? ... Illustrated by Terence Cuneo. London:

Oxford University Press, 1944. 208pp.

Reviewed in Locomotive

Mag., 1944, 50, 112

Translator

Gustav Reder. Clockwork, steam and electric. ; translated from

German by C. Hamilton Ellis. Ian Allan Ltd. 216pp.

Reviewed by Basil K. Cooper in

Railway

Wld., 1973, 34,

82

Letters

Drummond's "double singles".

Locomotive Mag., 1950,

56, 182.

Restoration of historic locomotves.

Locomotive Mag., 1930, 36,

359

Personal introduction (by CHE)

When I first knew the North British Railway, the Atlantic had just been flown. America's NC4 had hopped across via the Azores and the Peninsula; Alcock and Brown had made the first non-stop Atlantic flight in a converted Vickers-Vimy-Rolls bomber biplane, and the airship R34 had made the trip from Scotland to Long Island and back. A little later, in a third-class carriage of the Caledonian Railway, I read that the new R38, triumphantly sold to Washington, had broken herself over the Humber. Very advanced people talked mysteriously about home radio. But it was still rather smart to have a motor car. From Corstorphine to Joppa, Edinburgh swarmed with cable tramcars, and at Darling's Regent Hotel in Waterloo Place, a neat card in each bedroom invited us to join in prayers at nine o'clock in the lounge. When we drove over Glencoe, it was in a four-horse brake. Yes, it was a very different world!

A little later, as the newest and lowest form of animal life in a great school, I drove to it in Etons and a top hat, which was correct, and in a hansom cab, which was distinct lip on my part. Fortunately only the kindly Irish house servant saw me arrive. But that was in England, and in London, and has no part in the present account. To Scotland I went for holidays, as a very Englishy English boy, but my veins contained a 25 per cent. solution of Scotch, even then. Among my forebears I could count, so they said, a lady who had loved King James IV, and (it was whispered) a cold-blooded colonel who had helped considerably with the massacre of Glencoe. In my time this meant visits to Scotch cousins (they always used that sturdy adjective in those days!). They lived on the North British Railway, which had to be reached, very pleasantly, by the Midland. There at Melrose was the grand sweep of the Waverley Route below the Eildons, and while I romped with those agreeable girls on week-days, and rather impatiently joined them in the painting of pious mottoes on Sunday, I loved the North British Railway for its foibles as well as its splendours.

There, far more imposing than the pictures, were the magnificent Atlantics—Teribus, Buccleuch, Hazeldean, Waverley—hauling the Pullmans. There were Matthew Holmes's last and very beautiful engines, the 317 Class. To the eye of boyhood these were friendly-looking locomotives, not so proud as the Atlantics, nor so regal as the Midland compounds, and never in a thundering bad temper as were all the engines on the London & North Western Railway. They were more like a thickset version of certain favourites on my native London & South Western—another kind of Scotch cousin, no doubt. Over at St. Boswells were older veterans, and how pretty was the sight of a little Wheatley engine with her two-coach train from Berwick and Duns, slipping gently over the rosy arches of the Leaderfoot Viaduct of a summer evening! What wonder that a boy who loved engines should feel that, although foreign parts might begin when one crossed to the north side of the Euston Road, they ceased about Carlisle, so that somehow he was nearly home again among those great Border hills!

Now stern old Clio is acidly remarking over my shoulder that nostalgic vapours have no place in a book which ought to be given to more serious things-past. Let Clio cheer up and make the best of her author, who will do it again in one place and another; and forbye, let me hope that kind old Auntie Scotia will be tolerant of her South-Country nephew who takes upon himself to write about her!

The following extracts are largely self-explanatory, but obviously lack the illustrations which support the text in the book.

In Abraham Solomon's paintings Second Class—the Parting and First Class—the Meeting, there is the obvious moral of self-betterment. In the harsh, advertisement-plastered second-class compartment, poor Young Hopeful is travelling to join his first ship as its lowest form of animal life, with his mother trying to cheer him up and his sister on the verge of tears while he tries to keep his upper lip stiff. An old sailor behind looks across with sympathetic memories. Mother is apparently a widow untimely. In the Meeting, some years have passed and Young Hopeful has achieved gold-braided dignity as he sits in a well-appointed first-class compartment, gazing at a young lady who is obviously making eyes, while he ingratiates himself with her genial and prosperous sire. In a first version, the old gentleman was shown as being asleep, with the young people much closer together. It was condemned as being bawdy. The two pictures were exhibited as pendants at the Royal Academy in 1854, when people were particular.

The most successful painter of stories from contemporary life was William Powell Frith. In his two-volume autobiography—he was no modest man—he wrote of his hesitation in choosing such subjects. ... Eventually he realized his particular metier was the vast panorama, a microcosmic view containing all classes and types of society, full of anecdotal and dramatic incident. Ramsgate Sands, showing life at the seashore and Derby Day were enormous successes; Frith worked on each canvas for over a year, draughting rough outlines, posing models for every figure, making sketches for every group, using photography to help with backgrounds. His painstaking labours resulted in paintings with a rather static, tableau-like quality. Though fascinating they are a kind of hybrid art, a cross between painting and literature, weaving endless plots and sub-plots into a narrative whole.

In 1860 Frith began work on The Railway Station, an immensely profitable venture. Instead of exhibiting it at the Royal Academy, he sold it to Flatou, a dealer, for £4,500. After charging the public admission fees to see it, Flatou resold the reproduction rights for £16,000. To the Victorians, railway stations still conveyed glamour and excitement though Frith was doubtful about his subject:

"1 don't think the station at Paddington can be called picturesque, nor can the clothes of the ordinary traveller be said to offer much attraction to the painter:'

But he meticulously represented the decorative metal-work of Brunel's building and the Great Western Railway obligingly posed its best available locomotive for him. In the foreground baggage is being loaded on to the carriages, a mother sees her two boys off to school, a soldier kisses his plump baby goodbye, and a honeymooning couple is surrounded by their wedding party. A dark bearded man, his dress and binoculars suggesting that he is off' to the races, is arguing with a cabby over a fare. ... Frith's talents for observation and complex narration involving all classes of society are well displayed in The Railway Station. The Times complained that the work belonged to a class of art, "natural, familiar and bourgeois, as distinguished from the epic, ideal and heroic"...

Railway art finally flowered in the Impressionist paintings of Monet and Pissarro, who held to the myth of the "innocent eye". Consciously anti-intellectual and anti-theoretical, they never issued manifestos or tried to justify their art on any social or moral grounds. Monet wrote, "I have always had a horror of theories. I have only the merit of having painted directly from nature, striving to render my impressions in the face of the most fugitive effects". But while eschewing aesthetic theory, Monet can hardly have been unaware of it. His paintings were championed in the press by Zola; before 1860 he had frequented the Brasserie des Martyrs where Courbet used to preach to his disciples; still later he met Zola and Manet regularly at the Café Guerbois. Though no supporter of realism, he was still its child, and for two decades during the 1860s and 1870s his art reflects the stimulation of la vie moderne.

There are good reasons why the railway should have appealed to the Impressionists. They claimed to paint what they saw—and among what they saw were canal boats, viaducts, railway bridges and trains. The Impressionists wished to convey the quality of everyday life and to those painters who often met in the Batignolles quarter during the 1860s, trains were no novelty but a familiar sight; six lines converged at the nearby Pont de l'Europe and the Gare St Lazare was their point of departure for country excursions. A train rumbling over a bridge corresponded to the Impressionist sense of time; its very transience related to their idea of the fragmentary nature of experience and stimulated their desire to capture the truth of the instant. Moreover a train surrounded by steam and smoke, its lights glimmering through snow or fog, provided a new opportunity to study atmospheric effects. ...

In 1871, to escape conscription in the Franco-Prussian War, Pissarro and Monet moved to London. Pissarro wrote, "Monet and I were very enthusiastic over the London landscape" Monet worked in the parks, whilst I, living at lower Norwood, at that time a charming suburb, studied the effects of fog and snow in springtime" ..We also visited the museums. The water-colours and paintings of Turner and Constable" have certainly had their influence on us".

Undoubtedly the painters saw Rain, Steam and Speed for the motif of the train in a landscape setting appears in their own works during or shortly after this time; interior views or platform scenes could have had little appeal to them. While in England Pissarro painted Penge Station, Upper Norwood which shows a train approaching through a cutting in a bright spring-like setting. Monet's earliest known railway painting, Le train dans la campagne was painted in 1870. In 1875 he painted Le train dans la neige steam and smoke mingling with fog and snow, the orange headlights of the locomotive appearing like two great eyes. In the same year he painted the railway bridge at Argentueil; the bridge is seen from an oblique angle, a compositional device probably derived from Japanese prints.

On returning to Paris, Monet settled in a quarter near the Gare St Lazare. The huge enclosure with its glass roof, against which the locomotives threw their opaque vapour, the incoming and outgoing trains, the crowds, the contrast between the clear sky in the background and steam engines—all this offered subjects for his painting. Monet put up his easel in different comers of the station, returning to the station day after day, exploring it from a variety of angles, seizing the specific character of the place and its atmosphere. It was a new approach to a contemporary scene, but Monet's choice may have been at least partly dictated by his annoyance with critics who had satirized his earlier paintings.

Among his submissions to the third Impressionist exhibition of April 1877, Monet included at least seven canvases painted in or near the Gare St Lazare. Georges RiviŠre, in L'Impressionisme an art journal, compared one of Monet's locomotives to "an impatient fiery beast, animated rather than fatigued by the journey it has just completed".

There was nothing rarified about Ellis and he was willing to consider Monet alongside "F. Moore". The latter's style of craftsmanship shared more in common with those many anonymous painters who applied colour to coloured postcards before the perfection of colour photography, or in a very different field applied patterns to ceramics.

In view of newly awakened affection for the long-familiar steam train, and on their own peculiar merit, the 'F. Moore' paintings are of interest. They were never hung in the Royal Academy, though some are treasured now in London at the Science Museum. There never was such a painter as F. Moore, which was a trade name under which several painters worked, to an unchanging and meticulous style. Mostly the picture was painted over a blown-up photograph, in oils that were thinly applied but sufficiently.

Conclusion

Ellis's own contribution with the brush, rather than the pen, fell somewhere between F. Moore and Monet. Perhaps a fairer comparison would be to place him within a similar context to the great railway poster artists, such as Frank Mason, Tom Purvis and Norman Wilkinson,

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS (The North British Railway)

So complex is the earlier history of the former North British Railway,

especially on its mechanical side, that on attempting to put even its main

outline, with a general account of locomotives, into a book after all these

years, one cannot sufficiently express his indebtedness to those who have

gone before and pieced together this or that series of events. The first

to do so was A.E. Lockyer, who wrote a set of articles on the North British

for The Railway World during the eighteen-nineties, including a survey

of the engines then in service. In those days, the West Highland Railway

was just come into being; single-driver express engines were still working

between Edinburgh and Glasgow; no train ever went down from Cowlairs to Queen

Street with a locomotive, and none came up without cable assistance. Since

then, the railway has received attention from E.L. Ahrons, George Dow, Stirling

Everard and S.R. Yates, but only now, for the first time, does an author

presume to offer the public a full-dress book on it. He could not have done

so, even within his acknowledged limitations, but for those who had written

before, and in his present task he has received valiant assistance from Mr.

T.S. Lascelles, with his encyclopedic knowledge of signals, telegraphs and

other safety devices, from Mr. James F. McEwan, whose knowledge of Scottish

locomotive lore it would be an impertinence to appraise, and from the late,

much lamented Mr. Comyn Macgregor, whose sympathy transcended the fact of

his having been a Caledonian man. It may be pertinently remarked here that

Mr. McEwan has checked the dimensions of all the later engines against WaIter

Chalmers' book of diagrams, which thus becomes the author's standard.

People have helped, most willingly and disinterestedly, in the provision

of illustrations. One marks, with pleasure, the names of Messrs. R.B. Haddon,

W. Hennigan, J.E. Kite and H.A. ValIance; Mr. H.M. Hunter, Public Relations

and Publicity Officer, British Railways, Scottish Region; Beyer, Peacock

& Co., Limited, the North British Locomotive Co., Limited, and the Stephenson

Locomotive Society. Your author has been particularly fortunate in having

to draw upon the very -remarkable collections of Mr. Anthony Murray, Mr.

R.D. Stephen and Mr. L. Ward. The first- and last-named have furnished great

rarities from the remoter past; of Mr. Stephen's beautiful photographs, taken

in the last years of the North British company, people will learn with surprised

pleasure that they were the work of a boy in his 'teens, with a very simple

hand camera. C.H.E.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS (The South Western

Railway)

For reasons elsewhere stated, your author has been particularly anxious

that this short mechanical history of one of the most admirable of all railway

companies should look decent. So, while humbly inviting attention to its

treatment of the subject, he cannot too highly assess the devoted work of

his learned collaborators. Mr. Thomas Spooner Lascelles can be simply described

as the present national authority on the history and practice of railway

signals and telegraphs. Mr. John Pelham Maitland has been called, by appreciative

colleagues on the former Southern Railway, The Encyclopeedia, and his

encyclopsedics extend to other things beyond the lore of the locomotive and

the labyrinth of company history. Mr. Stephen Townroe has grown up in the

service of Eastleigh. He saw the re-building of the old South Western engines,

and their metamorphosis in Southern Railway days, he has known them both

as an engineer and as an artist, a rare and splendid combination. An author

feels safer with the advice and supervision of such mentors, named here in

the only possible order, which is alphabetical.

As remarked, this is a mechanical history. It has to do with engines and vehicles. A complete company history of the South Western has yet to be written, but much to be commended are Mr. G.F. Quartermain's articles in Volume LXXIX of The Railway Magazine. It is a pleasure, also, to record the germane passages in C.F. Dendy Marshall's History of the Southern Railway. Lesser men have been wise over some errors in that book, and worthier critics have anonymously rectified them, but on considering the enormous amount of material between its solid green covers, we are surprised, not by the occurrence of mistakes, but by their relatively low proportion in a book written, as so many books must be written, to a schedule. The marked copy belonging to the Curator of Historical Relics, British Transport Commission, has been of great value to the present author, as, also, has been access to the many documents freely made available by the B.T.C. Archivist. Illustration is important, and a price cannot be put on the willing help afforded by private collectors, whose names are acknowledged in the proper places.

A final tribute to the photographers, including those anonymous Mid-Victorian heroes who managed wet collodion plates amid the inconvenient surroundings of yards and running sheds, and developed them on the spot, all amongst the grubby cotton waste and smokebox char. Who recorded for us Pegasus, straight out of shops in 1868, or Waterloo A Box, what time he set up his massive tripod in the middle of the four approach roads, or Alaric in the Great Frost of 1881? We cannot know; but they were great artists.

London & North Western Railway West Coast Express, hauled by James McConnell’s “Large Bloomer” locomotive No. 607, leaving Shugborough Tunnel, by C. Hamilton Ellis. Carriage Panel picture commissioned by George Dow, for British Railways London Midland Region, c. 1951. Print panel size 25”x 10”, picture image 23”x 7.5”.

Stuart Rankin sent the following comments on this. In the days when

the majority of railway carriages were of the separate compartment type,

rather than the open saloons of today, the only alternative to looking out

of the window to making unwelcome eye contact with the strangers opposite,

was to stare at the luggage rack. A number of railways adopted the scheme

of displaying two or three sepia photographs of places served by the line

in the space between the opposing passenger’s heads, and the luggage

rack. These were of the “Promenade at Cleethorpes” variety, and

were still in situ in elderly carriages, long after the straw boaters and

long dresses of the figures depicted had ceased to be fashionable. Between

the Wars, attractive water-colours of villages, landscapes and historic buildings

were commissioned from well-known artists for use in new rolling stock.

However, apart from the occasional viaduct, few were of direct railway interest.

Around 1950, George Dow, P.R& P.O of the London Midland Region, and already

a noted railway historian, decided to brighten up travel in bleak austerity

Britain, by commissioning railway author and artist Cuthbert Hamilton Ellis

(1909-1987) to produce 24 oil paintings on the theme of “Travel

in…” featuring colourful trains and ships which had belonged to

companies swallowed up in the former London Midland & Scottish Railway

in 1923. This, featuring a scene in 1865, was No.8 in the series.

Hamilton Ellis was a good historian who, (unlike some of his contemporaries

who could have qualified for a “Queen’s Award for Re-cycling”)

undertook a great deal of original research but he was sometimes a little

out of his depth when dealing with the LNWR. According to

Locomotives of the LNWR Southern Division

by Harry Jack, the first of James McConnell’s “Large

Bloomers” appeared in 1851, (the name will be explained shortly) They

were larger engines than had been in common use on the Southern Division,

with 7ft driving wheels, and attracted considerable attention. The name

“Bloomer” was at first a nickname, but was quickly adopted officially.

The nickname was a topical one in the autumn of 1851 when the first engine

arrived on the line, because of the current popular excitement aroused by

the appearance of women wearing trousers, as advocated by a noisy American

propagandist, Mrs. Amelia Bloomer. Sixty were built, They were numbered

247–256, 287–296 and 389–408, until 1862 when they were renumbered

by the addition of 600, becoming 847 (etc.) to 1008.

Eleven smaller examples (logically “Small Bloomers) were built in 1854

with 6ft 6ins driving wheels intended for secondary fast main-line trains

and branch lines of the Southern Division. These engines were originally

intended by McConnell to be a 7 ft.-wheel variant of his Patent class, but

the design was altered by order of the directors to a smaller version of

the successful Bloomers. Numbers originally carried were an assortment from

2 to 381, renumbered 602 (etc. including 607) up to 981 in 1862.

As for the three “Extra Large Bloomers”, with 7ft6ins. driving

wheels built in 1869, they need not detain us further. They were more than

1.5tons over their designed weight and scarcely turned a wheel in service

before they were withdrawn because of track damage.

An enduring myth is that until 1862 the Bloomers (and other Southern Division

engines) were painted vermilion. They were not, although some were painted

a very dark plum-red from 1861, before the standard livery reverted to green

in the following year, and then changed to black from 1873.

So “Travel in 1865” is an imaginary scene. The locomotive depicted

is indeed a “Large Bloomer” but the number 607 belonged to a

“Small Bloomer”, neither type locomotive would have been painted

this shade of red at any time, and in 1865, both would have been green.

In fairness to Hamilton Ellis, much of the above information has only come

to light in recent years. If not strictly historically accurate, the painting

can at least be enjoyed as a spirited rendering of travel at this period.

I wonder if the artist was already mulling over a little joke which appeared

in his later writings. “There was no more stirring sight than a pair

of Large Bloomers on the front of the Down Irish Mail!”

|

|

And from The Times 26 September 1950 page 6 column D

The course of nature: the vocal grasshopper from a Correspondent who was

Hamilton Ellis

who reported on digging up a nest of wood ants in his garden and

liberating a giant green locusta which seemed to wish to escape, but

was recaptured by the ants.

In 1930 he lived at Ouzelwood, Ewell, Surrey

Letters: Locomotive Mag., 1935, 41, 132: on first class carriages

Updated 2022-07-10