|

Locomotives built for War or modified for War use |

Notes on british locomotives on active service.

Locomotive Mag., 1919,

25, 35-6. 5 illustrations

During WW1 about 700 locomotives belonging to the railways of the

United Kingdom were sent overseas to the various areas of operation for the

use of the Railway Operating, Department. Readers on active service sent

us at times notes of various locomotives that had come under their notice,

but, for obvious reasons, the information could not be published. Now that

the various restrictions had been withdrawn, we are able to publish photographs,

taken in France, of some of the engines and also an interesting snapshot

of two Belgian locomotives at Willesden, en route for heavy repairs at Crewe

Works. Practically all the locomotives sent overseas were of the goods or

mixed traffic classes. We have the numbers of 111 L. & N.W.R. engines

in France, eighty-five being of the 0-6-0 type and twenty-six 0-8-0. The

G.W.R. sent about sixty 0-6-0 tender engines, to France, as well as several

to Salonica, and the latter were provided with large cabs and sunshades.

Twelve of the new 2-6-0 mixed traffic engines were despatched as they were

finished off at Swindon (Nos. 5320 up) and were reported to have done excellent

work. Sixteen G.C.R. 0-8-0 and seventeen 0-6-0 were sent out in 1916, and

these were followed by two hundred and ninety-five of the 2-8-0 superheaters,

built to Mr. Robinson's designs by the North British Locomotive Co., Robert

Stephenson & Co., Naysmith, Wilson & Co., and Kitson & Co. The

North Eastern supplied over forty engines mostly of the 0-8-0 type, and we

understand two were sunk in a torpedoed ship. The G.N.R. sent overseas about

a dozen 0-6-0 goods engines and lent a few 0-8-0 mineral engines to the N.E.

Ry. The S.E. & C.R. were the first to send engines to France, these being

five 0-6-0 Kirtley side tanks, which were used for shunting at Boulogne from

the early days of the war. Forty-three goods engines were taken from the

G.E.R. stock, and about seventy or eighty from the Midland. Of the L. and

Y. 0-6-0 goods engines about thirty went to France, but we learn that several

0-8-0 compounds were at Salonica. Several 0-6-2 radial tanks were furnished

by the L.B. & S.C. Ry. for France. Thirty L. & S.W.R. goods engines

(built by Neilson) were sent to Egypt and Palestine, and four of these went

down in the Arabic. A few also were sent to Mesopotamia. Several trains

of North London carriages were in service at Salonica. Amongst the first

engines taken over by the R.O.D. were fifteen of the fine 4-6-4 tanks built

by Beyer, Peacock & Co. for the Dutch State Rys. A few Glasgow-built

4-6-0 tender engines intended for the Transcontinental Ry. of Australia were

diverted for service in France also. Of the Scotch railways the North British

and the Caledonian seem to have been the only lines to have supplied engines,

several 0-6-0 of both lines being reported. The Caledonian sent forty, and

it is worth noting their numbers have been filled up in the C.R. list. The

N.B.R. sent at least a dozen 0-6-0. The Baldwin Co. built seventy 2-8-0 tender

engines,

Aves, William. The Railway Operating Division on the Western Front:

the Royal Engineers in France and Belgium 1915-1919. . Donington: Shaun

Tyas, 2009. 208pp.

Reviewed by Grahame Boyes in

J. Rly Canal Hist. Soc,

2011 (210) [52-3]: This

book fills an important gap by concentrating on the ROD's 'broad' (i.e. standard)

gauge operations, rather than the tactical narrow-gauge lines that have received

most attention. Although the first Railway Company of Royal Engineers landed

in France within days of the onset of war, its role was to repair the railway

infrastructure; operation of the railways was still the responsibility of

the national railways. The ROD, employing largely volunteer professional

railwaymen from Britain and the empire, was not formed until 1915, when it

was agreed that the British army should take over railway operations supporting

the British Expeditionary 52 Force. Part 1 of the book (100 pages) describes

the strategic roles of the standard gauge railways, including the new lines

and operational facilities that had to be built to serve the 120-mile British

front and the variety of traffics and train that they handled. These included

trains of troops and their horses from and to the ports; ambulance trains

and 'sick horse specials'; supply trains of food and equipment; considerable

movements of materials for building and repairing railways and roads and,

under cover of darkness, the deployment of rail-mounted heavy guns and tanks.

Chapters on the ROD's 50 locomotive depots and workshops introduce Part 2,

the 80 pages of which are devoted to the histories of the 1534 ROD engines

that served on this front. The focus on locomotives will appeal to many,

but others will wish for more information on the volumes of traffic and the

intensity of train working. The book is attractively produced, with a very

interesting selection of photos.

Simpson, L.S. Railway operating in France.

J, Instn Loco. Engrs., 1922,

12, 697-728. (Paper No. 128)

Read in Argentina: Author describes how he returned to Britain to

serve during WW1 in the Railway Operating Division. On pp 699 and 700 he

encountered Colonel Cecil Paget who directed him

to repair 35 Belgian locomotives and noted on page 701 that Paget had a precise

knowledge of the French language. The repair work was performed in a sugar

factory (the source of some wonder to the speaker) at Pont d'Ardres, but

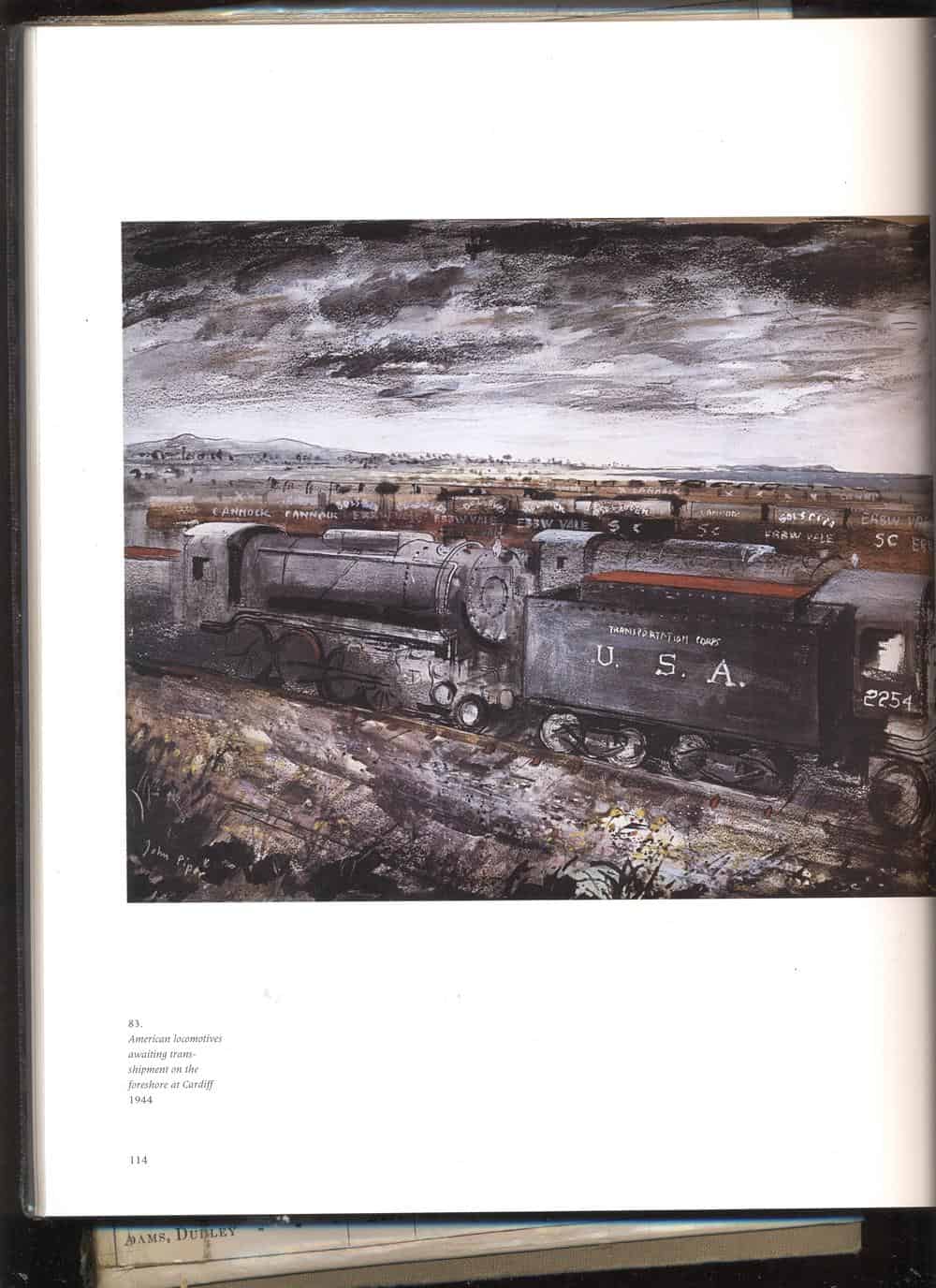

work had to be transferred when the beet crop was harvested. Also served

at Candas, Amiens and Hazebrouck. At the last named he experienced a major

ammunition explosion on 21 July 1917 involving 10-12,000 tons of ammunition.

On page 707 he recorded a visit made by

R.E.L.Maunsell and by

C.J. Bowen Cooke. He visited the shops

at Borre with Col. Paget. He worked under Colonel

George T. Glover, then of the NER, but later released to become CME

of the GNR(I) page 718. He was interviewed by Geddes and paper notes

several aspects of his invovement in France. He visited the Gaza Railway

in Palestine with Col. McLellan of Merz & McLellan to report on its state

and at the end of WW1 he was requested to assess damage to railways in Belgium.

Notes on train ferries.

Stanier, W.A. discussion on Burrows, M.G. and Wallace, A.L.

Experience with the steel fireboxes of the Southern Region Pacific

locomotives. J. Instn Loco. Engrs.,

1958, 48, 281-2. (Paper No. 584)

Noted the poor performance of the steel fireboxes fitted to the ROD

locomotives as experienced on the GWR and wondered whether wide fireboxes

were better suited to being constructed from steel.

ROD 2-8-0 (Robinson 8K design for GCR)

Modified with steel fireboxes and Westinghouse in place of steam

brake

Herbert, T.M. Locomotive firebox conditions: gas compositions and

temperatures close to copper plates.

Proc. Instn Mech. Engrs,

1928, 115, 985-1006

Part of a collaborative profamme between LMS, LNER and SR and British

Non-Ferrous Metals Research Association Included tests on ROD 2-8-0s working

from Mexborough with very poor water and another working in

Scotland.

R.S. McNaught. ROD memories.

Rly Wld, 1969, 30,

114-17.

Railway Correspondence and Travel

Society. Locomotives of the LNER. Part 6B. Tender engines—classes

O1 to P2. 1983.

Considers this variant of the Robinson 8K, LNER O4 class as part of

it

Reed, Brian. ROD 2-8-0s.

[Locomotive Profile No. 21]

Pp 193-216 (February 1972): centre spread (col. drawing: s & f

els). 9 tables. illus. selected to be informative rather than decorative.

Densely packed informative text.

J.W.P. Rowledge, The Robinson 2-8-0s. Part 1.

Rly Wld, 1969, 30,

172-6.

J.W.P. Rowledge. The Robinson 2-8-0s. Part 2.

Rly Wld, 1969, 30,

198-205.

The ROD and Robinson 2-8-0s—-a postscript: a selection of readers'

letters amplifying the articles in the March, April and May issues.

Rly Wld, 1969, 30,

368-70

Use by LNWR/LMS

In 1919 the LNWR purchased from the government thirty 2-8-0s which had been ordered for service with the Railway Operating Division on the Western Front during World War I. All except one were built by the North British Locomotive Co. and in fact came to the LNWR as new engines, since the war ended before they could be sent to France. They were classified as 'MM', the name being derived from the Ministry of Munitions which had ordered them, and lead to the adoption of the nickname 'Military Marys' by LNWR enginemen. When the engines were first obtained, they were given numbers in the LNWR ordinary stock list but the purchase was held up and in September 1919 they were numbered in the 2800 series along with 151 other engines of the class on loan. In November 1920 the purchase was completed and they received fresh numbers in the ordinary stock list. The Westinghouse pump provided brake power on the engine and so was in constant use when the engine was working; it was not something for use on the Continent only.

Essery, R.J. and David Jenkinson

An illustrated History of LMS locomotives. Volume One: General review

and locomotive liveries. 1981. page 90.

The ex-ROD engines (LMS 9616-65) were acquired by the LNWR and LMS

before and after the grouping. Of the LNWR acquisitions (9616-45), many did

not enter service until too late to receive their allotted LNWR series numbers.

The LMS did not seem very enthusiastic about these engines, in spite of their

relative newness, and scrapping commenced in 1928. In 1931,28 of the residual

31 survivors were renumbered 9455-82 to avoid clashing with the numbers of

the new Fowler 0-8-0s. All had gone by 1932 and it is interesting to contrast

the fate of these engines on the LMS with their considerable success on the

LNER and GWR systems. To be fair to them, however, they were faced with extensive

LMS route restrictions, being prohibited from virtually the whole of the

ex-L YR and ex-MR lines.

RCTS Locomotives of the Great Western

Railway. Part 10.pp. K269-75.

Covers the Great Western purchases of surplus ROD engines

Talbot, Edward. The London

& North Western Railway eight-coupled goods engines.

Chapter 10 of this excellent book covers the LNWR purchases

Topham, W.L. The

running man's ideal locomotive. J. Instn Loco. Engrs., 1946,

36, 3-29. Disc.: 29-91. (Paper No. 456)

Many failures were experienced with GCR ROD type due to lack of belling

and welding in steam pipe connections. The ashpan received specific condemnation

as the trailing coupled axle was completely surrounded..

Twenty six of G class served with ROD: see section on LNWR locomotives (part 3) references to Plates 376/7 (Talbot Illustrated history)

Two Ivatt 0-6-2Ts (Nos. 1587 and 1590) were purchased by the War Office for incorporation into armoured trains formed at Crewe with components from the GWR, CR as well as from the GNR. The locomotives were fitted with armour plating and the trains were known as HMT Norna and HMT Alice. In 1923 the locomotives were sold back to the LNER. Groves (3A) pp. 93-4. Talbot Pictorial tribute to Crewe Works PLATE 114

0-6-0T

L class (from NER)

The RCTS Locomotives of the

LNER Part 8B and Hoole Illustrated history of NER locomotives

(pp. 133-5) No. 544 illustrated is shown as modified (with No. 545) for hauling

large rail-mounted guns during WW1 when fitted with condensing apparatus

and an extra Westinghouse pump for lifting water from streams. According

to the RCTS No. 544 protected the entrance to the Tees from the Middlesbrough

side and No. 545 was at Hartley in Northumberland. Other Hoole illus: No.

553 Gateshead official; No. 551 in green livery; and No. 544 at Ferryhill

on 23 March 1923 after removal of condensing apparatus and one Westinghouse

pump.

0-4-0ST

Hatcher p. 64

states that a Manning Wardle 0-4-0ST was used to haul

an armoured train on the Marsden Railway during WW1.

Narrow gauge railways

Extensive use was made of tramways (light railways) which used troops,

horse and mules to haul munitions to forward positions. The French had developed

locomotive worked light railways to serve their fixed artillery firing sites

and these systems developed into complex networks of lines which were even

capable of coping in th later stages of the War with a more mobile form of

warfare. They are mainly associated with the Western Front, but were also

exploted to a lesser extent in Italy, Salonika, Egypt and Palestine.

Davies, W.J.K. Light railways

of the First World War: a history of tactical rail communication on the British

Fronts, 1914-18. Newton Abbot: David & Charles, 1966. 196pp.

58 illus. on plates, 35 diagrs (including many maps).

"At their greatest extent, during the months immediately preceding

the German offensive of March 1918, the light railways were operating, on

average, over 745 miles of 60cm-gauge track and carrying about 186,750 tons

a week, besides large numbers of troops." Main locomotive types described

were: Hudson outside-cylinder 0-6-0WTs supplied by

R. Hudson Ltd and manufactured

by Hudswell Clarke. The locomotives were known as "Hudsons". Twenty five

similar locomotives were supplied by Andrew Barclay (order placed in August

1916. These types were considered as "shunting locomotives", but were followed

by "main-line" locomotives supplied by Hunslet: 4-6-0Ts with outside-cylinders

and valve gear.These were 2ft 6in gauge. Davies considers that these were

popular with their crews and "were strongly-built, powerful, reliable and

comparatively stable". A total of 155 were supplied. The Baldwin 4-6-0Ts

of class 10-12-D were the most numerous: 495 being supplied to British War

Office orders. These were supplied very quickly, but were crudely built.

Davies argues that these were not pannier tanks. Later locomotives had flangeless

centre driving wheels with wide treads and built-in traversing jacks to assist

rerailing. Finally, 100 2-6-2Ts were ordered from ALCO and supplied from

the Cooke Locomotive Works, leading to the type being known as "Cookes".

The Baldwins tended to operate chimney-first, which called for triangles

for turning, whereas the 2-6-2Ta could operate in reverse. Davies also considers

two types of French military equipment which were sometimes operated by British

troops. These were the 60cm articulated 0-4-4-0Ts of the Pêchot-Bourdon

type. 100 locomotives were supplied by the North British Locomotive Co.,

plus a further 280 from Baldwin. Kerr Stuart supplied 100 0-6-0Ts which were

broadly similar to Decauville products and it is probable that these were

constructed to French drawings. Davies includes diagrams (side and front

elevations) for all the types mentioned excluding the French

designs. Reviewed by HS in

Rly Wld, 1967, 28, 357.

Narrow gauge military railway locomotives on the Western Front. Loco.

Rly Carr. Wagon Rev., 1920, 26, 120-2.

Hunslet 4-6-0Ts for 60cm lines. Built with condensing apparatus. Supplied

to design of Rendel, Palmer & Tritton.

1939-1945

This section includes four distinct categories of locomotive, namely:

- Locomotives built by the Ministry of Supply for the War Department, mainly for overseas military operations. Some were later absorbed into LNER and British Railways stocks. There were 2-10-0 and 2-8-0 classes designed by Riddles and a standard Hunslet 0-6-0ST.

- Locomotives acquired from the main-line companies for military service at home or overseas. These frequently required some modification. Notable amongst these were the LMS 8F 2-8-0s and the Robinson 2-8-0s used during WW1.

- Modifications to locomotives of the main-line companies to meet war time conditions.

- United States locomotives constructed for service in Europe. Some worked for a short time in Britain, and a few tank engines were eventually acquired by the Southern Railway. The main type was the S160 2-8-0: these worked for some months in Britain, but not without incident as there were several boiler explosions (see Hewison).

Kalla-Bishop, P.M.

Locomotives at war: army reminiscences of the Second World War. [1980].

Military railways at Martin Mill (serving artillery for Cross-Channel

shelling), Longmoor, Melbourne, Shropshire & Montgomeryshire, and briefly

service in Northern Ireland, and lengthier service in North Africa and in

Italy. Many observations on USA 0-6-0Ts, S160 2-8-0s and on Dean Goods.

Coincidentally, the writer describes some extraordinary motive power employed

on the Shropshire & Montgomeryshre Railway including LNWR 0-4-0STs Nos.

3014 and 3015, and 2-4-2Ts Nos. 6632 and 6691 which were highly unsuitable

for working permanent way trains (but maybe this was deliberate on a training

railway). J15 Nos. 7835 and 7541 (ex-film stars at Denham Studios) were also

in service). Dean Goods treated

separately..

Locomotives for war service overseas..

Locomotive

Mag., 1945, 51,

32

By the end of March 1945 the last 200 of well over 1,000 British and

American heavy freight locomotives will be withdrawn from service on British

railways and sent overseas. The withdrawal of engines from the railways commenced

early in the war, when a considerable number were shipped to France in support

of the first British Expeditionary Force. Many of these were lost after Dunkirk.

A further- 143 were later sent to the Near East, where they are operating

in Syria and Persia. Others have gone to Palestine and North Africa. The

first engine to enter El Alamein after its recapture was of L.M.S. design,

whilst G.W.R. locomotives have been seen hauling supplies along the North

African railways to Tunis. LNER. engines were working in Egypt and on the

Haifa-Beirut-Tripoli line. Military requirements in the Middle East in 1941/2

called for a number of diesel-electric locomotives, 16 of which were supplied

by the LMS. In all, 23 LMS. diesel engines had gone overseas. The latest

available figures show that 138 locomotives, including eight diesels, had

been lost overseas. In 1942 400 American 2-8-0 heavy freight engines were

loaned to the British railways to deal with the enormous quantities of additional

traffic consequent upon the US. Army being stationed in this country. These

engines, which were made ready at Eastleigh and Ebbw Vale works, have now

all been withdrawn and were in service on the Continent. Spare parts which

accompanied them ran into thousands. Towards the end of 1942 the War Office

agreed to lend the railways 450 specially designed 2-8-0 Austerity locomotives,

the first of which went into service in January, 1943. Others followed in

fairly rapid succession as they were completed by manufacturers, Progress.

of the Allied Armies in Europe made it imperative that these engines too

should be withdrawn from service in this country and, sent overseas, and

already 250 had been released by the railways and shipped to France and Belgium;

100 more were sent overseas during February and the remaining 100 are to

go during March. Arrangements were made for these to reach the ports for

shipment at the rate of over 20 a week. Prior to going abroad the whole of

the "Austerity" locomotives have undergone extensive overhaul in British

railway works, where they have been refitted and reconditioned to ensure

their running at least 25,000 miles trouble free. These final preparations

have been carried out in the railway workshops at Ashford , Cowlairs, Crewe,

Darlington, Derby, Doncaster, Eastleigh, Gorton and Stratford.

Ministry of Supply locomotives

Two tender designs were built under the direction of

R.A. Riddles.

2-10-0: 1944

This design incorporated a wide firebox. A few of the class were acquired

for use on the Scottish Region (mainly in the Motherwell and Grangemouth

areas), and the design had considerable bearing on the selection of

the 2-10-0 type by British Railways. Several

have been preserved, and having a light axle-load are useful on "preserved

railways", such as the North Norfolk Railway, where the type provides a

magnificent spectacle, especially with express headlamps: "90775" produces

a delightful amount of smoke and noises which can be heard far and wide across

the Sheringham area..

British-built Austerity 2-10-0 locomotive. Rly Gaz., 1944,

80, 468-70. illus., diagr. (s. el.), 3 tables.

BRITISH-BUILT Austerity 2-10-0 locomotive. Rly Gaz., 1944, 81,

597-602 + folding plate. 7 illus., 3 diagrs. (incl. s. el.), plan.

Includes sectionalized diagrams.

BRITISH-BUILT Austerity 2-10-0 locomotive. Rly Mag., 1944, 90,

222-5. 2 illus., diagr. (s. el.), table.

Cook, A.F. Ministry of Supply Austerity 2-10-0 engines. J. Stephenson

Loco. Soc., 1944, 20, 47. illus. (line drawing : s. el.)

MINISTRY of Supply 2-10-0 locomotive. Engineering, 1944. 158,

4; 10. 4 illus., diagr. (s. el.)

TEN-COUPLED locomotives again. Rly Gaz., 1944, 80, 461.

Editorial comment.

The 2-10-0 Austerity locomotive. Engineer. 1944, 177, 367.

2 illus.

Testing

1948 exchange trials.

Allen, C.J.. The locomotive exchanges, 1870-1948. [1950].

British Railways efficiency tests

British Railways. War Department 2-10-0 and 2-8-0 freight locomotives London, British Transport Commission, 1953. [5], 7, [55] sheets. 6 illus., 71 diagrs. (incl. 2 s. & f. els.), 3 tables. (Performance and efficiency tests with live steam injector. Bulletin No. 7),

Retrospective and critical

Bond, R.C. discussion on Burrows, M.G. and Wallace, A.L.

Experience with the steel fireboxes of the Southern Region Pacific

locomotives. J. Instn Loco. Engrs.,

1958, 48, 282-3. (Paper No. 584)

Noted the importance of water quality and treatment. The 25 WD

2-10-0s in Scotland had arch tubes and had given very satisfactory service,

but the Class 5 4-6-0s fitted with steel fireboxes had not been entirely

satisafctory.

British ten-coupled locomotives Rly Gaz., 1944, 81,

592-3.

Comment on good service in operation on the LMS.

Fairless, T. Recent locomotive designs a comparison between the

British-built Austerity 2-10-0, American-built Austerity 2-8-0 and proposed

2-10-0 locomotive for the Central Uruguay Railway. Rly Gaz., 1945,

83, 241+. 2 diagrs., table.

Harvey, D.W. Bill Harvey's

60 years of steam. 1986.

Pages 108-9: noted that the Flanery flexible stays initialy caused

confusion as one fitter thought that the dull thud when struck indicated

failure. The rubbing blocks between engine and tender tended to collapse

from impacts from heavy loose-coupled trains.

Pollock, D.R. and White, D.E.,

compilers. The 2-8-0 & 2-10-0 locomotives of the War Department,

1939-1945: Stanier L.M.S. type 2-8-0; British Austerity 2-8-0; British Austerity

2-10-0; Robinson L.N.E.R. class O4 2-8-0. Rly Obsr., 1946, 16

Supplement No.5.

In addition to describing the design, this work notes the war time

activities of the locomotives, in detail.

Poultney, E.C. British Railways freight locomotive tests. Rly

Gaz., 1954, 101, 346-8; 374-6. 2 illus., 19 diagrs., 5 tables.

An analysis of the official test bulletin (see above).

Railway Correspondence and Travel

Society. Locomotives of the LNER. Part 6B. Tender engines—classes

O1 to P2. 1983.

Pp. 147-51 includes some information relevant to the work of the 2-10-0

type on LNER lines during WW2. They did not receive an LNER classification.

Rowledge better known for his work on LMS and Irish locomotives contributed

to this Part.

Rogers, H.C.B. Last steam

locomotive engineer: R.A. Riddles, C.B.E. 1970.

This source is important as it appears that Rogers had the full

cooperation of Riddles: herewith the relevant section (page

The War Office were extremely pleased with the new engine, so much

so that they asked Riddles to produce a locomotive which should have the

same tractive effort as the Austerity but with only 13½ ton axle load

instead of 15½. This was a problem. Riddles first thought of a 2-8-2,

but he felt that he would lose adhesion and decided that a 2-10-0 was the

right answer, and that it should have a bigger boiler with a wide firebox.

To enable it to run through a 4½ chain curve, he decided that the centre

coupled wheels should be flangeless and those on each side have flanges of

reduced thickness. This caused some trepidation at the North British Locomotive

Company, but Riddles insisted. He had curves laid out and calculated that

with a wider wheel tread all would be well. The first of the engines to be

turned out was taken to St Rollox shed, and was just about to go through

a sharp curve when a ganger, who happened to be there, ran up waving his

arms and protesting that the engine could not go through as the curve was

much too sharp. But it went through all right without even the usual 'grind'

of a 2-8-0. Riddles says that they had got, in effect, the equivalent of

an articulated engine, because, with the slight flexing of the frames, the

2-10-0 was very easy on curves.

After the War, when the LMS was asked to take over some of these 2-10-0s,

the Civil Engineers objected to using them until they could test the 'throw-over'

on a 1 in 8 curve at a station platform. The argument about this went on

for some time, and Riddles believes that there was difficulty in finding

such a condition. He got tired of waiting and telephoned General McMullen

and asked him if he would make a test at Longmoor, where he knew there was

a 1 in 8 crossing in the station. This was a Saturday morning, and by the

Monday he had received a highly satisfactory chart of the complete test.

He presented this to the Chief Engineer, who then agreed to the engines being

used.

The demand for the 2-10-0 arose because the 2-8-0 was not considered suitable

for the haulage of very long and heavy trains over light, improvised, or

imperfect track. As compared with the 2-8-0, the 2-10-0 had a considerably

longer boiler and with the wide firebox the grate area was increased to 40

square feet. A rocking grate was provided. Riddles decided on a more orthodox

lagging of the boiler because of the extremes of temperature to which it

might be subjected. Underneath the steel clothing plates were asbestos

mattresses, laid against the boiler barrel and firebox.

Riddles' 2-10-0 class, the first of which was completed by the North British

Locomotive Company in June 1944, was undoubtedly one of the masterpieces

of British locomotive engineering. Major General D.J. McMullen, Director

of Transportation, wrote to Riddles on February 15, 1945 saying that he had

just come back from a visit to the British Liberation Army and had to let

him know how excellently the Austerities and 2-10-0s were doing. 'Everyone',

he wrote, 'loves the 2-10-0. It is quite the best freight engine ever turned

out in Great Britain and does well on even Belgian "duff", which is more

like porridge than coal. The 2-8-0s have trouble for steaming on this muck

alone, but if they can get 25 per cent of Dutch lump coal mixed with it they

do all right'. He added that it was amazing to trundle along on a 2-8-0 Austerity

only three miles from the German front line. In Nijmegen station the shell

bursts in the battle area could be seen from the footplate, 'So your products

are well up into the fighting area, often ahead of the medium artillery

positions'. On January 4, 1946 McMullen wrote again to Riddles saying, 'I

have yet to see in Europe anything to touch your 2-10-0, weight for weight'.

A total of 150 of these engines were built, all by the North British Locomotive

Company.

Riddles had returned to the L M S by the time the first of the 2-10-0s began

to appear. Stanier was still CME (though he retired early in 1944), and one

Saturday he walked into Riddles' office. 'Bad luck, Robert,' he said. Riddles

was at that moment being told by Walters, from the Ministry, that seven or

eight of the 2-10-0s had been stopped at Peterborough with broken stays in

the firebox. He asked Stanier how he knew as he had only just got the information

himself. Stanier replied that it had been given out over the 'tin can'. This

was the name given to the daily telephone conference, held under the authority

of the then Railway Executive, between operating officers of all railways

and at which were reported and discussed arrangements for traffic control,

untoward incidences, etc. Riddles says:

'Stanier was not malicious—in fact I do not think he could be but I

knew that many others did not like my having produced new designs. I replied

lightheartedly (without, of course, intending it unkindly), "It reminds me

of the crisis with the Class Fives and their broken stays". We said no more,

but, in spite of my assumed lightheartedness, I was very worried. It was

a Saturday, so I was back early at my home in Watford and immediately got

out my car and drove off to Peterborough. Just as I arrived at Peterborough

station, to enquire the whereabouts of the running shed, I saw coming round

the corner Tom Lawson, the North British Works Superintendent. He had a broad

grin on his face when he saw me. "What is it Tom?" I asked. "The bloody fools

have been tapping the flexible stays!" he replied. I breathed a sigh of relief,

and how we both enjoyed it! But no correction was announced over the "tin

can"!' (Normally, when stays are tapped with a hammer they give a ring if

they are sound and a dull thud if they are not. But flexible stays, being

linked together, also respond to a tap with a dull thud.) The Directorate

of Royal Engineer Equipment controlled all locomotive manufacture, and this

included Beyer Garratt locomotives for Commonwealth countries, Colonial

territories, and the lines of communication of the forces operating in Assam

and Burma. Many other requirements were met by using or adapting existing

types of, for instance, both steam and diesel shunters.

Rowledge, J.W.P. Austerity 2-8-0s & 2-10-0s. London:

Ian Allan, 1987. 144pp.

Author is extremely reliable and contributed to RCTS work (above).

The 2-10-0s were all built by North British Locomotive Company and had a

more limited sphere of activity, both overseas and in Britain. Before the

end of WW2 they were used quite extensively on the LNER both in Scotland

and in East Anglia. prior to most going to Europe. On p. 43 there is an evocative

picture of No. 73704 on a leave train consisting of LNER coaches at Breda

on 11 July 1945. This type had a long association with the Longmoor Military

Railway. The type worked in Syria and in Greece where they lasted for a long

time after WW2. Some worked in Holland and in Germany. On page 36 it is noted

that the tenders were prone to derail when running tender-first. On British

Railways they were mainly asociuated with workings from Motherwell, Kingmoor,

and to a more limited extent from Grangemouth..

Rowledge, J.W.P. Heavy goods engines of the War Department. Vol.

3 Austerity 2-8-0 and 2-10-0. Poole: Springmead, 1978. 64pp.

Ottley 10491

Thomson, W. Discussion on

Burrows, M.G. and Wallace, A.L. Experience with the steel fireboxes

of the Southern Region Pacific locomotives. J. Instn Loco. Engrs,

1958, 48, 297-8. (Paper No. 584)

The steel fireboxes fitted to the WD 2-10-0s were remarkably free from trouble

and that the firebox stays lasted for fifteen years.

Tourret, R. War Department locomotives. Abingdon: Author. 1976.

82pp.

Ottley 10488

Vaughan, Adrian. The heart

of the Great Western. Peterborough: Silver Link, 1994.

Relates how Charlie Turner (page 56) found these to be "fine engines",

when they were enountered during WW2 in France and Germany.

Whalley, P.S. The work of their

craft. J. Instn Loco. Engrs, 1946, 36, 401-29. 28 illus., 8

diagrs., map (Presidential Address).

Includes some comments on the British Austerity designs, but it is

mainly concerned with the United States "Liberation" type.

Numbers and names

NORTH British 2-10-0 locomotives Rly Gaz., 1945, 83, 278.

The last engine to be built was named North

British.

Railway Correspondence and Travel Society. British Railways renumbering

of class 8 2-8-0 and 2-10-0 W.D. locomotives. Rly Obsr, 1949,

19, Supplement No. 3. 6 p.

2-8-0:1942

In its original form this design was simple to the point of crudeness.

All refinements were eliminated to ensure reliability under military operating

conditions.

The "AUSTERITY" locomotives. Engineer, 1942, 174, 448. diagr.

(s. el.)

BRITISH "Austerity" locomotives. Rly Gaz., 1943, 78.101.2 illus.

Handing over ceremony at the North British Locomotive Co.

BRITISH-BUILT "Austerity" 2-8-0 type tender locomotive. Rly Gaz.,

1943, 79, 253-8 + folding plate. 7 illus., diagrs., 5 tables.

Includes sectionalized diagrams.

Cook, A.F. Ministry of Supply "Austerity" 2-8-0 locomotive. J.

Stephenson Loco. Soc., 1944, 20, 35-7. illus. (line drawing: s.el.)

Ministry of Supply "Austerity" locomotive.

Loco. Rly Carr. Wagon

Rev., 1942, 48, 202. diagr.

(s. el.)

Ministry of Supply 2-8-0 tender locomotive.

Loco. Rly Carr. Wagon Rev.,

1944, 50, 9. illus.

No. 7199 supplied by North British Locomotive Co.

Ministry of Supply "Austerity" locomotives. Rly Gaz., 1942, 77,

492-3. illus., diagr. (s. el.)

NEW locomotives for War work. Rly Mag., 1943, 89, 44-5. illus.

diagr. (s. el.)

[WAR Department 2-8-0] . Rly Gaz., 1943, 78, 116. illus., diagr.

(s. el.).

Testing

1948 exchange trials.

Allen, C.J.. The locomotive

exchanges, 1870-1948. [1950].

British Railways efficiency tests

British Railways. War Department 2-10-0 and 2-8-0 freight locomotives London, British Transport Commission, 1953. [5], 7, [55] sheets. 6 illus., 71 diagrs. (incl. 2 s. & f. els.), 3 tables. (Performance and efficiency tests with live steam injector. Bulletin No. 7),

Retrospective and critical

Beavor, E.S. Steam was my calling. 1974 pp. 83-4.

Slipping: describes how at Staveley in 1952, the examining fitter

there came to him with the expression of a man who has just seen a flying

saucer, and announced "You'll hardly believe this, but I've found an 'Austerity'

with a set of flanges on the outside of the coupled wheels as well as on

the inside". Normally this would have gone well beyond the limits of my

credulity, but examiner Walt Airey was a serious, long-service type, .whose

remarks were in no way inclined to imagination. So I went along with him

to investigate. Sure enough this WD 2-8-0 had been slipping to such an extent,

in trying to drag a heavy train out of a colliery yard, that it had produced

the equivalent of some years of normal wear on the wheel treads. Evidently

the driver had been using sand continuously on wet, greasy rails, and this

had acted as a very effective grinding paste. As a result, all the coupled

wheels had a crude kind of 'flange', between ¼in and ½in deep on

the outside of the treads, in addition to the normal flanges being cut

correspondingly deep.

Blundell, J. communication on Topham's The running man's ideal locomotive.

J. Instn Loco. Engrs., 1946,

36, 68-71

The water valve control of some W.D. locomotives was so designed

that the whole rodding up to the actual handle bracket had to be stripped

to change the plug cock which was seized owing to being bulged by frost.

Dismounting alone took a fitter forty minutes.

Bond, R.C. Organisation and control

of locomotive repairs on British Railways. J. Instn Loco. Engrs, 1953,

43, 175-216. Disc. : 217-65. (Paper No. 520).

Quotes mileages achieved between repairs.

Bulleid, O.V.S. discussion on

Shields, T.H.: The evolution

of locomotive valve gears. J. Instn Loco. Engrs., 1943, 33,

368. (Paper No. 443).

Pp. 454-6: "As a matter of interest, he had compared the valve events

of the first "austerity" engine built on the Southern Railway with those

of the second "austerity" locomotive, produced by the Ministry of Supply.

The Southern Railway engine used the Stephenson gear; the Ministry of Supply

used the Walschaerts. When one looked at the figures, one had to admit that

it was quite immaterial whether one used the one or the other; the events'

were both good, both engines did the work for which they were designed, and

both stood up to their job. The Stephenson gear did not cause any trouble

with lubrication. It was piston ring trouble rather than gear trouble which

was generally experienced.

Cox, E.S. British Railways

standard steam locomotives. 1966.

Page 24 et seq. Cox summarises the background activities which

led up to the Austerity 2-8-0 design.

Essery, Bob. LMS Garratts.

Steam Wld, 2009 (263),

28-39.

Annual mileage statistics quoted for LMR Austrities for 1950: 19,121

miles.

Hardy, R.H.N. Steam in the

blood

Again I decided to see for myself and one evening set off with White

for Neasden on the 6.4spm from Woodford. Again I did the hard work and there

was no doubt that 3188, our engine on this trip, would not steam in the best

of conditions. The oscillation between engine and tender at speed brought

a constant stream of coal on to the footplate, making it impossible to keep

things clean, and I was tired out when eventually I got back home at about

four in the morning. I was even more so when I set out for the depot after

breakfast to sort things out with Joe Goode and Bill Jeynes, respectively

chargeman fitter and boilermaker, who came to see me each morning at nine

o'clock and stood in front of my desk like Tweedledum and Tweedledee answering

questions that I hoped sounded more confident and incisive than I felt they

were. And thus began the battle of the "jimmies".

Some of the WD engines still had their original numbers, such as No 785I4,

while those that had been through the Faverdale shops had received new

numbers—63186, 63188, and 90046. Generally speaking those which had

passed through the shops had a large blastpipe top, of either

51/8in or 5¼in diameter. Whatever the size, however,

the steaming was very bad. On the other hand, some of the older engines with

the WD numbers were fitted with a form of "jimmy", three studs fixed to a

ring which in turn was fitted to the blastpipe top. The studs restricted

the blastpipe orifice and sharpened the blast so that the boiler steamed

freely. Now it was expressly forbidden to fit any such device, and so I was

faced with a difficult situation. Time was being lost day after day on the

Neasden service through shortage of steam. I knew perfectly that to obtain

authority to alter the design would take months, and I decided that the only

quick solution-for we were there to run trains to time-was to make and fit

a razor across the blastpipe of the engines with the large tops, bolting

it securely in place. As a result, time- keeping became exemplary, but our

boilermaker chargeman went about with a long face, feeling that the boilers

were being forced and tube leakage accentuated. On the contrary, I felt very

strongly that if the blastpipe tops were too large, the "jimmy" simply had

the effect of making the boiler do its stuff.

However, our firemen never liked the WD flame-scoop, and the firehole mouthpiece

that fell into the fire at the slightest touch. Bill Jeynes had plenty to

say, too, about cold air on his tubeplates, so we devised a method of fixing

the mouthpieces and altering the set of the flame-scoop. I could stand in

my office and look across the front of the shed and if I saw a WD 2-8-0 about

to go out without a flame-scoop in place, I would dive out of the front door

and up on to the footplate to remonstrate (to put it mildly) with the crew.

Maybe they cursed me, but we got those old "carts" to steam, to do their

work, and to run to time, and we eased the terrible leaking of the tubes

that was a constant worry to all concerned. And provided we took the "jimmies"

out when the engines went to the works for overhaul, everybody was happy.

Certainly we reduced the number of discarded flame-scoops dumped at

the far end of the triangle and in the station yard, and that in itself was

a major triumph.

Pollock, D.R. and White, D.E.,

compilers. The 2-8-0 & 2-10-0 locomotives of the War Department,

1939-1945: Stanier L.M.S. type 2-8-0; British Austerity 2-8-0; British Austerity

2-10-0; Robinson L.N.E.R. class O4 2-8-0. Rly Obsr., 1946, 16 Supplement

No.5.

Powell, A.J. Living with London Midland

locomotives. 1977.

Chapter 10: The strong pull:

Any review of freight locomotive power would be singularly incomplete without

some mention of the WD 2-8-0s, or 'Austerities'. I make no apology for mentioning

these engines in the company of LMS designs, because apart from the features

introduced by Mr Riddles to facilitate production under wartime conditions

they were as LMS-bred as anything from the Derby drawing-boards. In fact,

a number of LMS draughtsmen were seconded to North British for the design

work. The starting point was, of course, the Stanier 2-8-0, with as many

castings as possible eliminated, with coupled wheels designed to be suitable

for cast iron (though in practice iron was abandoned quite early in favour

of cast steel) and a round-top firebox on a parallel boiler barrel. Mechanical

lubrication was eliminated in the interests of economy, and another feature

introduced with this in mind was the absence of a smoke box ring to the barrel,

resulting in a smokebox smaller in diameter than the boiler clothing. In

a number of respects the design improved on the LMS model. The Midland brake

valve was discarded for a 'Dreadnought' valve with separate graduable steam

brake valve. The exhaust steam injector and Midland live steam injector were

replaced by two 'Monitor' injectors — really first-class devices. The

LMS reversing rod from the cab a flat-section rod with a lot of 'whip', which

needed a steadying bracket, was passed over for a stiff tubular rod. They

were built for a short life and a gay one during the war, but that life was

so short under wartime conditions, and there was so much sound potential

in them, that there was no thought of scrapping them after hostilities ceased.

Altogether some 733 2-8-0s and 25 2-10-0s were bought by the LNER and BR

on behalf of several Regions, and put into heavy freight service after overhaul,

enabling scrapping of much old power to be undertaken.

During 1949, while I was at Railway Executive headquarters at 222 Marylebone

Road, the first distillation of experience with the 'Austerities' took place,

and this led to a lengthy list of proposed modifications. Some arose from

complaints through trade union channels, some were based on (bitter) maintenance

experience and a few from other sources. They were of various degrees of

priority: some were done at next works repair, while some never did get done

because a satisfactory solution to the problem could not be devised within

acceptable cost limits. The top priority jobs included the fitting of sliding

side windows and gangway doors to the somewhat spartan cabs, the restaying

of the smokebox tubeplate and firebox doorplate in the upper areas to eliminate

the original plate gusset stays which gave trouble, and the replacement of

the water gauges by either LM or BR standard fittings. The original water

gauges were absolute fiends: if the left-hand glass broke, it was almost

impossible to shut off the cocks unless you were wearing asbestos gloves,

so badly were the handles placed close to hot stea.m pipes, etc. In addition,

the crosshead gudgeon pins had a nasty habit of falling out — they were

not nutted, but held in by a triangular plate secured by three very inadequate

studs. As they were shopped the crossheads were bored out and fitted with

LM-type gudgeon pins, fitted in the body of the cross head on two seatings

of a continuous taper, and nutted. and cottered on the outside — which

stopped that little game. Other items need to be outlined. Enginemen had

some surprises (and maybe a few injured legs) when, under certain conditions

of curvature and cant, the cab fall-plates could dig into the corners of

the steel tender platform and then fly up under pressure. Nasty! All the

platform corners had to be reprofiled to stop this happening. The tender,

too, was distinctly prone to derailment. The four axles were equalised in

two pairs, but the equalising beam pins soon became seized and the weight

distribution went all to pot. Various palliatives were tried, but the problem

was never fully bottomed and cured. It was such a regular occurrence that,

for instance, when they were taken into Crewe Works from the South shed,

the tenders were solemnly filled with water before starting and emptied on

arrival in the works.

Being built for an austerity age, the mechanical lubricators of the Stanier

engines were replaced by oil boxes to feed the axleboxes (via a telescopic

pipe arrangement that was nearly as crude as on the LNW engines) and a sight

feed lubricator for cylinders and valves. There was a degree of hot box trouble

as a result of displacement and fracture of the oil pipes, and on occasion

the oil boxes themselves did not get the attention they warranted (there

were four quite big ones on each side for the coupled boxes). The real answer

was to fit mechanical lubricators delivering straight into the underkeeps,

but the cost was reckoned to be prohibitive. A few were fitted with a small

Wakefield 'Fountain' type lubricator in the cab for the boxes, but this was

only partly successful. Consideration was given latterly to putting hoses

from the original oilboxes to the underkeeps, but I do not think this ever

came to fruition. There was a stupid little difficulty on the 'Detroit' cylinder

lubricator, too. The filling plug was screwed into a renewable seating, the

idea being that its constant use should not wear or strip the threads in

the main body prematurely. Fine in theory; but in practice the seating always

unscrewed with the plug. We tried all sorts of ways of fixing that seating

— set screws, brazing, the lot — but it always came out with the

plug after a few days.

On the credit side there was quite a lot to be said in their favour. Unkempt

they generally looked, but they were rugged and reliable. The steaming was

satisfactory from the start, but after a visit to the Rugby test plant which

led to the fitting of slightly smaller blastpipe caps it was as near perfect

as could be. There were two really good live steam injectors on them, very

reliable at all times. The Laird crossheads, with bolted-on slipper, were

a joy for the maintenance staff —they could have the slipper out, remetal

it and have it back, without need for machining if they had the proper chills,

in an hour. And while the tender, with its narrow bunker, did not give the

same degree of cab protection as the Stanier 4,000 gallon design, the bunker

was perhaps a little better at feeding coal when part-empty, thanks to the

steeper inclination at the sides. Also the 5,000 gallon capacity (with no

scoop) could be a godsend. But, once again, they experienced all the shuttling

trouble from total absence of reciprocating balance. It seemed particularly

bad on the 'Austerities', to the point that the engine and tender drag-boxes

behind the intermediate buffing blocks distorted quite seriously, and had

to be stiffened up with additional gussets. We also tried to stiffen up the

intermediate buffers by was he ring up the springs, but this was of strictly

limited effectiveness. But on some of the Central Division banks, such as

coming down from Copy Pit, I think if you could have fitted a straight Image

chute from shovelling plate to fire hole the engine would have fired itself!

...

There was just one engine of the class that did not suffer this shuttling

malady - No 90527, which had been experimentally modified, by riveting steel

plates on the outside of the cast balance weights, to balance 40% of the

reciprocating masses — the maximum that clearances would permit. I rode

on her throughout one night on the 10.40pm Class E freight (not less than

four wagons vacuum-braked) from Aintree to Copley Hill, a test if ever there

was one — 7miles down from Todmorden, and 3miles down from Morley Tunnel

(steep), as well as all sorts of short bits between. But on none of these

banks, even at speeds up to 45mph, and using the graduable steam brake valve

to steady the train rather than get assistance from the fitted head, could

we get her to shuttle. The various engine men involved were quite incredulous,

thinking that something wonderful had been done to the intermediate drawgear

to effect such an improvement (in fact, nothing had been done to it at all).

She was completely cured, but it took a long time to persuade the CME that

he should do anything more. Finally, he took No 90527 on some official,

instrumented tests. And the finding? She was no better than other Austerities

and it had not really mitigated her shuttling. We were utterly dismayed -

it could only have happened by getting the wrong engine by mistake. So nothing

more was heard of it and they shuttled into Valhalla. They will be remembered

for their chunky bark, the gentle knock of their motion, and the many times

one or two pairs of tender wheels were disengaged from the ballast.

Poultney, E.C. British Railways freight locomotive tests. Rly

Gaz., 1954, 101, 346-8; 374-6. 2 iflus., 19 diagrs., 5 tables.

An examination of British Railways Bulletin No. 7 (see

above).

Railway Correspondence and Travel

Society. Locomotives of the LNER. Part 6B. Tender engines—classes

O1 to P2. 1983.

The type was classified as O7 by the LNER and considerable numbers

were purchased by the Company prior to Nationalization. The boilers, especially

the fireboxes were considered to be below standard by Darlington and were

subject to extensive modification.

Riddles, R.A. discussion on Koffman, J.L. Dynamic braking of

steam, diesel and gas turbine locomotives.

J. Instn Loco. Engrs., 1951, 41, 490-536. Disc.: 537. (Paper

505)

Explained Sillcox’s trouble (the paper had opened with an extensive

quotation from L.K. Sillcox's Mastering momentum. New York, 1940).

It had little to do with the heavy braking found with heavy stock in America;

but was primarily due to the the American use of chilled cast iron wheels.

When working for the Ministry of Supply he thought that if chilled cast iron

wheels could be used successfully with the heavy rolling stock in America

Britain could probably take advantage of the rapid production achievable

with chilled cast iron wheels, and they were fitted to the tenders

of the “austerity" locomotives only to find that although he reduced

the brake percentage to make sure that they were not applied too hard, the

practice was to put the brake on by the steam brake, screw the hand brake

down, release the steam brake and run down the gradients with the hand brake

not only screwed on but put on with the steam pressure, and they had all

the trouble of cracks and galls on the tyres. This to such an extent that

they changed all the wheels to steel, after which there had been no further

trouble.

Rogers, H.C.B. Last

steam locomotive engineer: R.A. Riddles, C.B.E. 1970.

This source is important as it appears that Rogers had the full

cooperation of Riddles: herewith the relevant section (page 118 et seq):

Now Riddles was to attempt another rush job in conjunction with the North

British Locomotive Company and again to assay a locomotive straight off the

drawing board (refers back to Royal Scot)... The Chairman of the North British

Locomotive Company, with whom Riddles was to deal so much, was W. Lorimer,

the son of Sir William. Each week for many weeks on end Riddles travelled

to Glasgow on the Friday night. There he spent Saturday in the North British

Locomotive Company Drawing Office and Sunday with James Black the Technical

Director. He says that he drew the Drawing Office staff and the Works together

in a manner never experienced, even in the North British Locomotive Company.

If a component was designed which was difficult to manufacture the design

was altered.

The Austerity engine had some relation to the LMS 2-8-0 because the outline

scheme had been got out by F.G. Carrier, a draughtsman who was section leader

in the development and design branch of the Derby drawing office. (Carrier

was, indeed, largely responsible for what Stanier's and Riddles' engines

looked like.) For ease of manufacture Riddles had chosen a parallel boiler

with a round top firebox, rather than the intricate and expensive Churchward

pattern of taper boiler with Belpaire firebox. He almost eliminated steel

castings, cutting down the 22 tons needed for the LMS 2-8-0 to only 2½.

Cast iron replaced steel castings for all except the driving wheel centres.

The leading truck wheels were rolled in one piece, and the tender wheels

were chilled cast iron. But here Riddles slipped up. He had seen heavy freight

wagons in the USA with these sort of wheels and observed how badly they behaved

when over-braked. He had arranged for the percentage of brake leverage to

be lowered on the tender to avoid this, but he had not allowed for the prevalent

practice of drivers, when descending, a bank with loose-coupled stock, to

apply the steam brake fully, screw down the tender hand brake, and then release

the steam brake. This had most unfortunate results, for the tender wheels

were badly damaged. Fortunately this happened in the early days and there

was time to substitute rolled forged wheels. (He heard afterwards that the

Chairman of one of the Railway Companies had said that the leading truck

wheels were cast iron!) Another trouble was that a slight 'fore-and-aft'

movement caused the built-up draw bar buffer between engine and tender to

collapse, but stronger control springs remedied this. It was apparent that

hostile and critical eyes were watching his engine, but he did not bother

too much because he was sure that he was on the right lines.

With vivid memories of the trouble he had experienced with crossheads on

the LMS Pacifics, Riddles chose the Laird pattern with twin bars above the

piston rod (which were also much cheaper to manufacture). As stated earlier,

he dispensed with boiler lagging and used air insulation only between the

boiler and steel clothing sheets. There were two outside cylinders, 19 inches

by 28 inches, driving the third pair of coupled wheels, which were 4 feet

8½ inches... The valve gear was Walschaerts and, of course, outside.

The boiler pressure was 225 lbs. per square inch, the grate area was 28.6

square feet, and the weight of the engine in working order was 72 tons, of

which 62 tons were available for adhesion. Cab and footplate arrangements

were simplified as far as possible.

Riddles never approved of undue emphasis on thermal efficiency. The basis

of his engines was a boiler which would meet all the demands made of it.

He says, 'Whether or not they would burn a pound or two more a mile than

a more sophisticated engine, I regarded as the unrealistic preoccupation

of the theorist, because in practice a good driver and fireman could save

pounds if given a free-steaming engine.'

Riddles anticipated a great deal of criticism of the Austerities and he

remembered that his old friend Charles S. Lake, Editor of The Railway

Engineer, had once said to him that the first thing that anybody noticed

about an engine was the chimney. If, therefore, one wished to deflect criticism,

the best way to do it was to design a ridiculous chimney. The critics would

then concentrate on that and forget about the rest of the engine. So Riddles

put an absurdly small dumpy chimney on his engine which was three inches

lower than the rest of the boiler mountings. In diverting criticism from

the more controversial points of the design, the results were highly gratifying.

Nevertheless, he was too much of an artist for the chimney to be really ugly,

and the Austerity, unlike Bulleid's dreadful looking 0-6-0 for the Southern

Railway, was a handsome engine. (This chimney had an unexpected bonus because

when Riddles designed the later and larger 2-10-0s for the War Department

it was just right for the most exacting restrictions of the British loading

gauge.)

Riddles awaited the appearance of the Austerity locomotive with a certain

natural anxiety. On November 23, 1942 he wrote toW. Lorimer, Chairman of

the North British Locomotive Company, asking him to do all in his power to

get the first engine out by the end of the year at the latest and if possible

before Christmas. He added:

'I think you are aware of the antagonism of the Chief Mechanical Engineers

to this engine, and our one hope of getting it running on the British Railways

is to produce it at a time when they are desperately in need of power and

will be forced to take it in hand. When this has been done, I am quite sure

that the locomotive itself will prove so effective in service that all their

criticisms will be overriden and it should be accepted with joy by the

operators'. He went on to say that the first American locomotive was arriving

in a few days and there was a big 'poohbah' to greet it, in which he was

joining, mainly as a return for the welcome given to the 'Coronation Scot'.

But he did not want the shade of its arrival to last too long and obscure

the impact of the home-made Austerity.

Lorimer replied on November 25th, saying that since he had received. Riddles'

letter he had been in discussion with those of his staff concerned in the

matter; but he did not think there was any possibility of steaming the first

Austerity engine that year. He said that there had been difficulties over

supplies, material, labour, and existing contracts.

But it was not long after the end of the year, because the first of the Austerity

2-8-0 locomotives was handed over at the North British Locomotive Company's

Works on Saturday January 16, 1943. It was inspected by Sir Andrew Duncan,

Minister of Supply, and among those present were Sir William Douglas, Permanent

Secretary Ministry of Supply, Sir Geoffrey Burton, Director General of Mechanical

Equipment, Riddles, W. Lorimer, and J. Black. The engine had been built in

five months from the date of placing the order, and after all the parts had

been delivered it had been assembled in ten days. The speed with which it

was built was, in fact, a record for the North British Locomotive Company.

The previous record had been five months from the time the designs had been

received. According to the Glasgow Herald, William M'Pherson, the

driver, said, 'This is the first time I have had a cushioned seat for my

work, and altogether I have never handled a better engine'.

Production of the Austerities was rapid, because, owing to the simplicity

of the design and the use of more readily available materials, thousands

of man-hours were saved and time lost waiting for parts was drastically cut.

Whereas the LMS 2-8-0s were being built at the rate of two to two and a half

a week, the Austerities were turned out more than twice as fast, for from

five to six were produced each week, and with the help of other manufacturers

this rate eventually rose to seven. And, as a result of Riddles' visits,

week-end after week-end, to Glasgow, and although the engines were produced

straight off the drawing board, there were no teething troubles, apart from

the quickly remedied errors over the tender wheels and draw bar buffer. It

is only necessary to remember the Royal Scots to appreciate what a triumph

of design this was. But it was an anxious time, fol' the engines to be built

without prototypes or trial were eventually to number, not 70 like the Royal

Scots, but no less than 935—second only to Ramsbottom's DX goods as

the largest class of British locomotives ever built. 'The decision to do

this', Riddles says, 'required courage, because there were so many critics

of my policy who were only awaiting a chance to "pounce".' (Of the 935, 545

were built by the North British Locomotive Company and 390 by the Vulcan

Foundry.) Since these engines were turned out in advance of military needs,

no less than 450 were lent to the Railway Companies, and did excellent service

before they were withdrawn for shipment from October 1944 onwards. Of these

350 ran on the LNER, 50 on the LMSR, and 50 on the SR. The LNER got their

first engine in February 1943, and it made its first run from a Glasgow goods

yard on a freight train on the West Highland line.

Rowledge, J.W.P. Austerity 2-8-0s & 2-10-0s. London:

Ian Allan, 1987. 144pp.

Author is extremely reliable and contributed to RCTS work (above):

covers design, development, builders (NBL and Vulcan); loans to mainline

companies during WW2; notably the LNER, but all four companies had some allocated

(even the Southern Railway), military service in France, the Netherlands

and Belgium, the Middle East, notably Syria, and the Far East, Hong Kong.

Locomotives were acquired by both the Netherlands where modifications in

the form of smoke deflectors and taller chimneys were made, and in Sweden,

In the Netherlands they were known as Dakotas. In Sweden the locomotives

were fitted with totally enclosed cabs and cut-back tenders with only six

wheels. On page 36 it is noted that the tenders were prone to derail when

running tender-first. Locomotives returned to Britain: some were sold to

the LNER and became class O7 where some received numbers beginning 3000 and

some had the British Railways prefix 6 added. Many ran for a long time with

their 77XXX numbers. Rowledge does not attempt to list all the variations,

but the photographs illustrate some of the variety: for instance No. 3165

with WD on tender and 21st Army shield at Neasden on 14 August 1947 and in

E3119 in Scotland. No. 3152 is shown as fitted for oil-burning in 1947; 63077

at Wormit on 4 June 1949 and 63118 near Hitchin on 28 May 1949.. Many ran

for a time with their air compressors still in place.

Rowledge, J.W.P. Heavy goods engines of the War Department. Vol.

3 Austerity 2-8-0 and 2-10-0. Poole: Springmead, 1978. 64pp.

Ottley 10491

Taylor, Charles. Fore & aft: balanced running trials for the 'WD'

2-8-0s. Steam Wld, 1991

(54), 6-11.

Running trials on scheduled freight workings between Aintree and Leeds

via Rose Grove and Copy Pit using No. 90527 which had been modified to give

40% balance in an endeavour to reduce the severe oscillation which limited

their use. The writer worked at Crewe and the experimental modification of

1951 was Experiment M/C/L/1413. Footplate observations showed that the experiment

was a success, but this did not lead to further locomotives being

modified.

Tourret, R. War Department locomotives. Abingdon: Author. 1976.

82pp.

Ottley 10488

Vaughan, Adrian. The heart

of the Great Western. Peterborough: Silver Link, 1994.

Relates how Charlie Turner (page 56) found these to be crude and

uncomfortable when encountered in France and Germany and were not tolerated

by US WW2 drivers.

Venning, Roger. Taunton

in January 1947. Gt Western Rly J., 2004, 7, 52-3.

Illus. of 70843 and 77161 both with air compressors, latter with smoke

deflector in front of chimney.

Whalley, P.S. The work of their

craft. J. Instn Loco. Engrs, 1946, 36, 401-29. 28 illus., 8

diagrs., map (Presidential Address).

0-6-0ST:1943

This design was based on a standard Hunslet industrial locomotive.

The LNER purchased 75 engines at the end of the war (classified

them as J94) and the National Coal Board adopted it for colliery

working.

AUSTERITY tank locomotive: Ministry of Supply. Loco. Rly Carr. Wagon

Rev., 1943, 49, 34-5. illus.

Cook, A.F. Ministry of Supply "Austerity" 0-6-0 saddle tank locomotives.

J. Stephenson Loco. Soc., 1944, 20, 28. illus. (line drawing

: s. el.)

0-6-0 saddle-tank. "Austerity" locomotive. Engineering, 1943,

155, 155. illus.

SADDLE-TANK "Austerity" locomotive. Rly Gaz., 1943, 78, 146.

illus.

A VALUABLE locomotive spare parts list the Hunslet Engine Co. Ltd. has prepared

an unusually comprehensive brochure covering details of its 0-6-0 saddle-tank

shunting locomotive. Rly Gaz., 1944, 80, 186-9. illus., 5 diagrs.,

plan, 2 tables.

Extracts from it.

Austerity 0-6-0 saddle tank, B.R.

Loco, Rly Carr. Wagon Rev., 1952,

58, 147. illus.

Describes them as J94 class which is not strictly true as built for

National Coal Board by Hunslet Engine Co. to same dimensions, but with better

quality fittings. Order for twelve locomotives in hand and order for further

37 placed by NCB at cost of £350,000. See also

feature in Locomotive October 1950.

Retrospective and critical

The AUSTERITY tanks-their origin and operation.

Loco. Rly Carr. Wagon Rev., 1950,

56, 161-4. 3 illus., diagr. (s. & f. els.), 3 tables.

A very complete account, which includes the origin of the design,

performance in service and a stock list.

Railway Correspondence and Travel

Society. Locomotives of the LNER. Part 8B. Tank engines—classes

J71 to J94. 1971.

Although there was a second impression of this part in 1983 Part 8B

is far less developed than Part 6B dealing with the 2-8-0 classes which served

in WW2 and the section on the J94 is really quite thin considering that it

became an LNER "standard class".

Rogers, H.C.B. Last steam

locomotive engineer: R.A. Riddles, C.B.E. 1970. page 124

In response to a War Office request for steam shunting locomotives

of the same capacity as the LMS Class 3 Freight 0-6-0 shunting tank engine,

Riddles chose the Hunslet standard shunter, a very fine little 0-6-0 saddle

tank and much better than the LMS engine cited. But, as in the manufacture

of the Austerities, the materials available and the nature of its employment

would necessitate extensive modification before it would be suitable for

mass war construction. Steel castings and forgings, for instance, would have

to be replaced by fabricated parts, the wheels would have to be of cast iron

and increased in size, coal and water capacity would have to be increased,

brass tubes would have to be replaced by steel, etc. Riddles asked Mr Edgar

Alcock, Chairman of the Hunslet Engine Company, to come and see him. This

meeting was followed by discussions between the Directorate and Hunslet and

Riddles went himself to Leeds to visit the firm. Delivery

of the modified locomotives which resulted began at about the same time as

the first of the Austerity 2-8-0s made their appearance. Eventually 377 of

these shunting engines were built by six different firms.

Tourret, R.and Latham, J.B. The locomotives of the War Department

and United States Army. Part No. 31. The standard 0-6-0ST-W.D. numbers

1437-56/62-1536; 5000-5199; 5250-5331. Rly Obsr, 1959, 29,

78-80; 120-2. 5 tables.

Main-line stock acquired for military duties

The principal classes involved were the LMS 8F 2-8-0s, which were the standard military locomotives until the Austerity designs superseded them, and the LNER 04 class and GWR Dean Goods (both of which had served in a similar role during WW1).

8F:1935: Stanier:

The design is considered in greater

depth in the section on Stanier's locomotives. Locomotives were constructed

within the workshops of the other mainline companies, including Swindon and

Brighton.

BRITISH locomotives for the Middle East. Rly Mag., 1942, 88,

20.2 illus.

Modifications for overseas service.

BRITISH rolling stock for service overseas : details of the 240 locomotives

and 10,000 covered wagons ordered by the Ministry of Supply for use with

the British Expeditionary Force. Rly Gaz., 1940, 72, 83-5.

illus., 2 diagrs. (incl. s. el.)

[CAB and front-end illustrations of class 8F as modified for Middle Eastern

conditions]. Rly Mag., 1942, 88, 114. 2 illus.

[CLASS 8F : 240 constructed for service in France]. Rly Gaz., 1940,

72, 777. illus., diagr. (s. el.)

Ikeson, W.C. Development of the oil-fired locomotive.

J. Instn Loco. Engrs., 1952,

42, 425-75. Disc.: 475-515. (Paper 516)

Operation of 8F class on the Iraqi State Railways where the Author

was CME.

ROLLING stock for the B.E.F.. Loco. Rly Carr. Wagon Rev., 1940,

46, 144-5. illus., diagr. (s. el.)

Modifications for French conditions.

Retrospective

Chacksfield, J.E..Ron

Jarvis: from Midland Compound to the HST. 2004. .

A great deal of this excellent biography (with one serious reservation)

covers (1) Jarvis's interesting WW2 exploits in bringing into service 8F

locomotives exported from the United Kingdom for service in neutral Turkey

(this work clearly brought together engineering and dipolmatic skills of

the highest order: subsequently . He was assisted by Fred Soden, an artisan

forman from Crewe. Jarvis's fluency in French was a significatnt attribute;

(2) Jarvis was responsible from bringing back 8F locomotives from the Middle

East in April/May 1948 (including dangerous Palestine) via the Suez Canal

Zone for further service on the LMS/LMR. Interesting illus of SS Belnov

with 11o

list.

Copsey, John. Swindon's '8Fs'. Great

Western Rly J., 2004, 7, (51)165-76.

Those locomotives built at Swindon and used briefly on the GWR before

being passed onto the LMS. The locomotive men were not altogether happy with

these modern locomotives.

Notes on Stanier "8F" 2-8-0 engines. J. Stephenson Loco. Soc.,

1956, 32, 84-8. illus., table.

Pollock, D.R. and White, D.E.,

compilers. The 2-8-0 & 2-10-0 locomotives of the War Department,

1939-1945: Stanier L.M.S. type 2-8-0; British Austerity 2-8-0; British Austerity

2-10-0; Robinson L.N.E.R. class O4 2-8-0. Rly Obsr., 1946, 16

Supplement No.5.

WAR Department Stanier 2-8-0s. Rly Obsr, 1948, 18, 204-5.

table.

Notes on locomotives returned to the United Kingdom.

Railway Correspondence and Travel

Society. Locomotives of the LNER. Part 6B. Tender engines—classes

O1 to P2. 1983.

Locomotives built at Darlington were classified as LNER class O6 and

"LNER" was applied to the tenders. They were handed over to the LMS at the

end of WW2.

Rowledge, J.W.P. Heavy goods engines of the War Department. Vol.

2. Stanier 8F 2-8-0. Poole: Springmead, 1977. 64pp.

Ottley 10491

Whalley, P.S. The work of their

craft. J. Instn Loco. Engrs, 1946, 36, 401-29. 28 illus., 8

diagrs., map (Presidential Address).

Considers the 8F class in relation to war service.

O4/3: 1917: Robinson

During the First World War the Robinson GCR 1911 design was selected

and built as the standard Railway Operating Division's design. A few of the

class were re-called for service in the Second World War.

BRITISH locomotives for the Middle East. Rly Mag., 1942, 88,

20. 2 illus.

L.N.E.R. locomotives for overseas. Loco. Rly Carr. Wagon Rev., 1941,

47, 256. illus.

Retrospective and critical

McNaught, R.S. The Robinson "R.O.D." 2-8-0s. Trains ill., 1957,

10, 432-8. 10 illus., table.

Pollock, D.R. and White, D.E.,

compilers. The 2-8-0 & 2-10-0 locomotives of the War Department,

1939-1945: Stanier L.M.S. type 2-8-0; British Austerity 2-8-0; British Austerity

2-10-0; Robinson L.N.E.R. class O4 2-8-0. Rly Obsr., 1946, 16

Supplement No.5.

Postscript on the Robinson 2-8-0s. Trains ill., 1958,

11, 148-51. 4 illus., table.

A summary of the material received as correspondence in response to

McNaught's article (above).

Railway Correspondence and Travel

Society. Locomotives of the LNER. Part 6B. Tender engines—classes

O1 to P2. 1983.

Includes their lesser role during WW2: they had a major role in

WW1.

Sherrington, C.E.R. Locomotives of the Railway Operating Division,

Royal Engineers, 1916-1919. Part 4. Ministry of Munitions locomotives. Rly

Mag., 1932, 71, 425-30. 3 illus.

The Robinson 2-8-0s.

Rowledge, J.W.P. Heavy goods engines of the War Department. Vol.

1. The R.O.D. 2-8-0 and 2-10-0. Poole: Springmead, 1977. 72pp.

Ottley 10491

0-6-0

Dean Goods

Kalla-Bishop, P.M.

Locomotives at war: army reminiscences of the Second World War. [1980].

Encountered by author on the Martin Mill Railway where the condensing

modified locomotives were set the task of propelling the guns used for

Cross-Channel shelling, on the Shropshire & Montgomeryshire where the

livery (p. 91) normally considered to be "desert sand" or near khaki had

been replaced by a dark green or near camouflage colour. Type was also

encountered in Tunisia (WD No. 171).

Vaughan, Adrian. The heart

of the Great Western. Peterborough: Silver Link, 1994.

Relates (pp. 53 et seq) how Charlie Turner worked on Dean Goods

during WW2 hauling rail-mounted guns on the Kent & East Sussex Railway

and on the Elham Valley line.

0-6-0T

Chacksfield, J.E..Ron

Jarvis: from Midland Compound to the HST. 2004. .

Jarvis is increasingly known for his WW2 exploits with the 8F class

and for returning locomotives from the Canal Zone. He also "found" some of

the missing 3F 0-6-0Ts which had gone out with the BEF. Following WW2 these

were discovered at Savenay in France and returned to Britain

Tourret, R. The locomotives of the War Department and United States

Army. Part No. 10. L.M.S. standard class 3F 0-6-0Ts: W.D. 8-5. Rly Obsr,

1951, 21, 47. table.

J69:1902 : J. Holden (GER/LNER)

Kalla-Bishop, P.M.

Locomotives at war: army reminiscences of the Second World War. [1980].

Nos. 7041 (J68) and J69 Nos. 7054, 7056, 7088, 7271, 7344, 7362 and

7388 were at Longmoor in March 1940, but were sent elsewhere from May 1942.:

they were renumbered WD 84-91.

Railway Correspondence and

Travel Society. Locomotives of the LNER. Part 8A. Tank

engines—classes J50 to J70. 1970.

Classes J69 (thirteen locomotives) and a single J68 were used as shunters

mainly at Faslane and Cairnryan. They were not handed back to the LNER at

the end of WW2.

Tourret, R. The locomotives of the War Department and United States

Army. Part No. 17. Ex. L.N.E.R. class J69 0-6-0T's: W.D. 78-91. Rly Obsr,

1953, 23, 24-5. table.

4-4-2T

I2: 1900: Marsh (LBSCR/SR)

Tourret, R. The locomotives of the War Department and United States