|

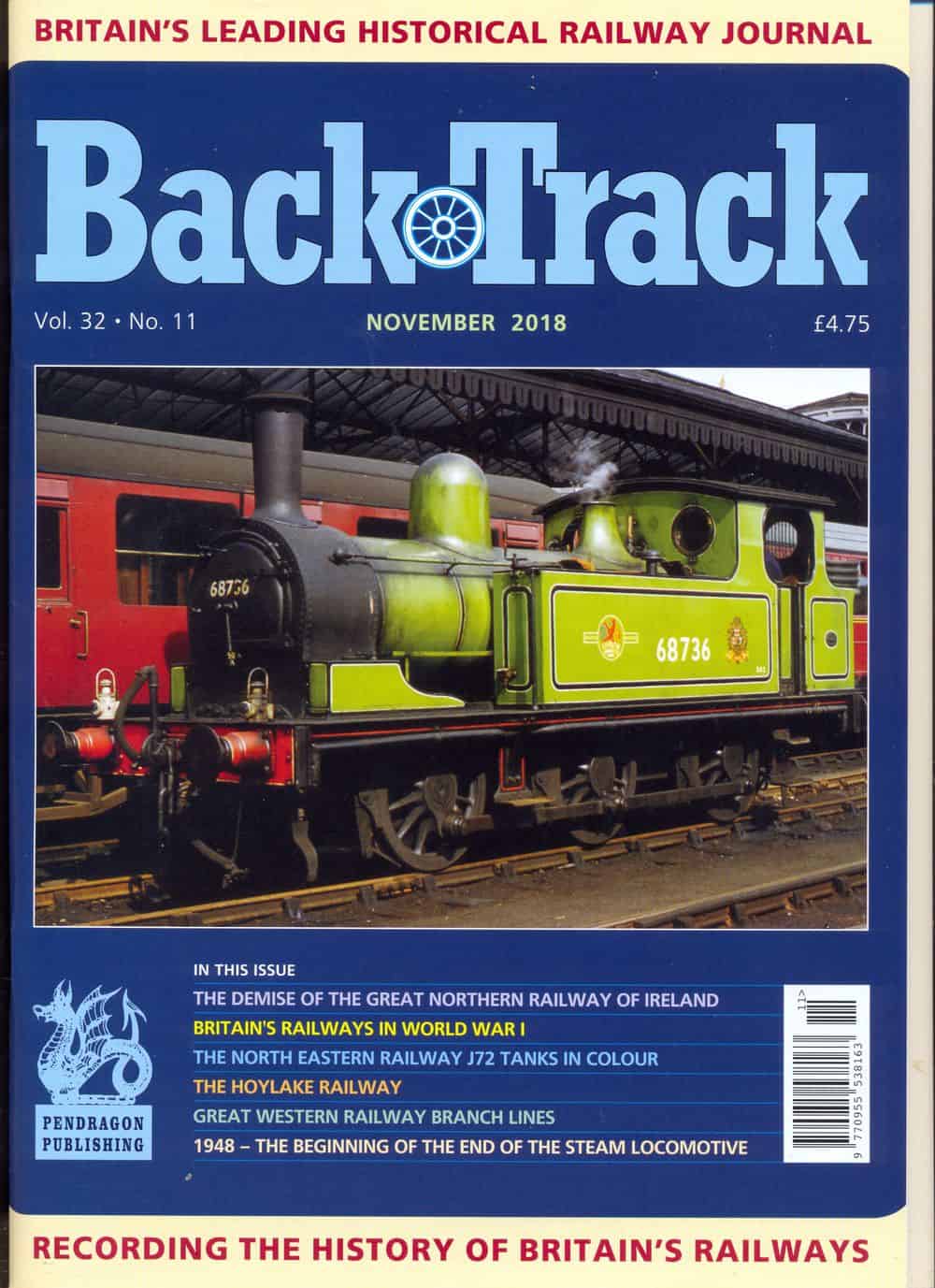

November (Number 331) |

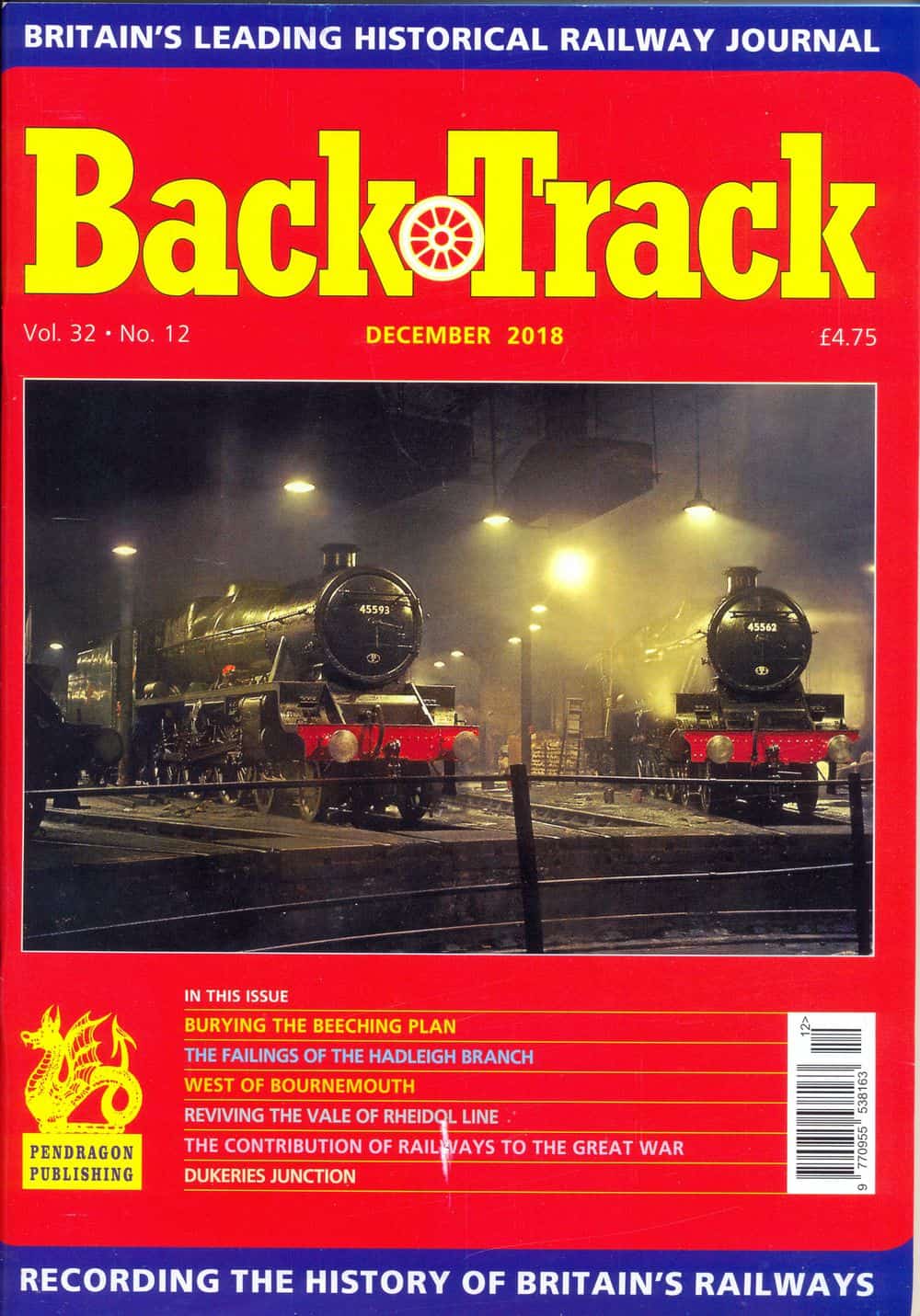

Backtrack Volume 32 (2018)

| Home page | January | February | March | April | May | June | ||

| Previous volume | July | August | September | October | November | December | Next Volume |

Published by Pendragon, Easingwold, YO61 3YS

| January (Number 321) |

LNER Kl Class 2-6-0 No.62021 at Alnwick station with the branch train to Alnmouth on 10th May 1966. G.F. Bloxham. front cover

Backtrack through the looking glass. Michael Blakemore. 3

Editorial with a pinch of Lewis Carroll

TJE' at Birmingham New Street. John Edgington. 4-7

Black & white photofeature as memorial to the late John Edgington

who was born in City and worked for LMS/London Midland Region thereat. Prince

of Wales 4-6-0 No. 25752 on 12.20 to Stafford on 8 December 1948; Webb coal

tank 0-6-2T No. 58900 acting as station pilot on 21 June 1951; rrebuilt Patriot

No. 45522 Prestatyn in mixed traffic lined black livery with tender

lettered BRITISH RAILWAYS on 3 April 1950; Class 3P 4-4-0 No. 40745 on pilot

duties with Compound No. 1028 behind on `9 April 1949 (these first photographs

demonstrate WW2 damage to station); Patriot No. 45539 E.C. Trench moving

off Manchester to Bournemouth Pines Express on 25 May 1957 (rear of

Queen's Hotel behind); Jubileee No. 45592 Indore waiting to take up

British Industries Fair Express on 9 May 1955; B1 4-6-0 No. 61195

having ar4rived an 06.63 from Cleethorpes on 20 October 1956; Caprotti and

double chimney class 5 4-6-0 No. 44687 on 17.08 to Napton & Stockton

on 29 April 1955; 2P 4-4-0 No. 40659 and rebuilt Scot No. 46148 The Manchester

Regiment on 11.05 to Glasgow Central on 28 October 1954; Jubilee No.

45733 Novelty on 17.50 Euston to Wolverhampton on 8 June 1953 (locomotive

carrying a crown headboard to celebrate Coronation); 4P Compound No. 41193

on 13.45 to Yarmouth Beach on 8 October 1958; A1 4-6-2 No. 60114 W.P.

Allen on 11.41 Birmingham to Newcastle on 8 August 1964.

John Jarvis. Change at Verney Junction. 8-15

In Buckinghamshire. The London & North Western Railway had a long

branch line from Bletchley to Oxford which had a further branch line to

Buckingham and Banbury. The Aylesbury & Buckingham Railway was conceived

by local landowners Sir Harry Verney and the Mraquis of Chandos, later the

Earl of Buckingham and who was also Chairman of the LNWR as a means of increasing

their wealth. The growth and protracted shrinkage of the railways, including

the WW2 Calvert Spur are outlined as well as a possible futture as part of

a revived Oxford to Cambridge line. Illustrations: Derby light weight railcar

at Verney Junction on an Oxford to Bletchley service (colour); map showing

convoluted railway lines (many of which are closed) and their former ownership;

Verney Junction station c1900 with Metropolitan Raiulway train and its passengers

changing to another service via footbridge; Sulzer Peak class diesel elctric

locomotive No. D16 on a Leeds to Wembley Cup Final special on 1 May 1965

passing through Verney Junction (colour); Verney Junction on 30 June 1963

(colour: Ron Fisher); Class 5 No. 45292 passes on freight in 1963; plans

(station layouts in 1878 and 1896; Standard class 2 No. 84004 at Verney Junction

on Bletchley to Buckingham push & pull (Roger Jones); plans (LNWR,

Metropoltan Railway, BR (M); Metropoltan Railway K class 2-6-4T No. 115 on

freight leaving Verney Junction for Quainton Road on 4 July 1936 (A.W.V.

Mace); Metropoltan Railway signal box in mid-1950s; LNWR signal box in September

1967 (colour: author); Class 56 No. 56 046 on Hertfordshire Railtours Mothball

rail tour on 29 May1993. See also letter from Gerald Goodall

on page 189.

Eric Stokes. Auto suggestions. 16-25

Stream push & pull operation: outlines the terminology and the

methodology: the Great Western used mechanical linkage to operate the regulator.

Vacuum control gear was used by the LMS and LNER, but the Southern standardised

on compressed air control. The LNWR and LSWR had used mechanical transmission

via wires along the roofs of the train sets. [Kevin observed and sometimes

travelled on the Delph Donkey and is far from certain of the origins of some

of the rolling stock used see Frank page].

Illustrations: Webb 2-4-2T No. 46712 on Dudley "motor" at Dudley Port in

1949 (colour); ex-GCR F2 2-4-2T No. 5780 propelling 11.45 Alexandra Palace

to Finsbury Park at Stroud Green on 11 August 1945 (H.C. Casserley); H class

0-4-4T No. 31177 at Dunton Green with push & pull for Westerham in July

1960 (colour: D.H. Beechcroft); GER F5 2-4-2T No. 67202 at Ongar with push

& pull set for Epping on 7 June 1954 (T.J. Edgington); 14XX 0-4-2T No.1432

propelling 11.55 ex-Ellesmere to Wrexham at Marchwell on 25 February 1961

(Alan Tyson); Ivatt Class 2 2-6-2T No. 41223 at Four Oaks with push &

pull unit for Birmingham New Street in October 1955 (colour: E.S. Russell);

M7 0-4-4T No. 40058 approaching Lymington Pier with paddle steamer alongside

in October 1953 (colour); Lemon 2P 0-4-4T No. 6408 at Stanmore with Harrow

& Wealdstone push & pull on 16 June 1934; C15 4-4-2T No. 67460 at

Gerelochhead with Craigendoran to Arochar & Tarbet push 7amp; pull in

May 1959 (Unusual in that corridor, but non-vestibuled coaches used with

first class accommodation and lavatory used); (colour: D.H. Beechcroft);

H ckass No. 31177 leaving Mainstone West on 15.08 for Tonbridge on 10 April

1961 (Alan Tyson); H class 0-4-4T No. 31530 at Rowfant on Three Bridges to

East Grinstead service in July 1960; L&:YR 2-4-2T No. 50731 leaving Sunny

Wood Halt with a Bury to Holcombe Brook push & pull on 3 February 1952

(N.R. Knight); Ivatt 2-6-2T No. 41276 on The Welsh Dragon at Deganwy

with Rhyl to Llandudno summer service (colour); C15 No. 67474 at Shandon

with Craigendoran to Arrochar service in 1960 (colour); 14XX 0-4-2T No.1432

propelling 11.55 ex-Ellesmere to Wrexham at Overton on 25 February 1961 (Alan

Tyson); Lemon 0-4-4T No. 41900 at Upton-on-Severn with push & pull t/from

Ashchurch on 19 July 1958 (T.J. Edgington); and cutting edge standard 2-6-2T

No. 84007 at Uppingham with service for Seaton See also

page 190 for letters from David Holt and from Andrew

Kleissner on modern push & pull (but

no mention is made of Sykes) and from J. Whiteing on

p. 253.

Mike Fenton. Byway of the 'Barra' - Part One.

26-30

Haltwhistle to Alston branch: partly personal reminiscences of the

branch line when it was under sentence of closure; and partly a history of

a line which dated back to the Newcastle & Carlisle Railway and was promoted

by the Earl of Carlisle to reach the lead mines at Nenthead and an Act was

obtained for a branch line from Haltwhistle on 6 August 1846, but the route

selected was too difficult and an easier route limited to reaching Alston

was approved on 13 July 1849. Illustrations: Alston station on 29 March 1964

(colour: John M. Boyes); panorama of Alston station viewed from above c1903/4;

Haltwhistle station with trains and turntable with Alston Arches over Tyne

in background c190s; map; Lambley Viaduct and station on 26 March 1967 with

Scottish Rambler crossing it; Slaggyford station c1900; G5 0-4-4T no. 67315

at Alston with passenger train in 1957; BTP 0-4-4BT No. 69 in South Tyne

during recovery in 1920; camping coach with Jean Gratton on

the steps see letter from Philip A. Millard on sole

bar lettering; A8 4-6-2T No. 2146 mear Broom House with train for Alston

(E.E. Smith). Part 2 see page 165.

L.A. Summers. The naming of engines: an afterword.

31

Evidence provided via Peter Rance, Chairman of the Great Western Trust

on how the names selected for the initial broad gauge locomotives. The evidence

comes from a printed tender document of 10 September 1840 issued at Paddington

as a Specification of locomotive engines with seven feet driving wheels wherein

"The Splashers covering the large wheels shall be neatly made in brass according

to drawing (No. 2), and the Name of the Engine shall be put in brass letters

upon each side of the framing...". Although parts of the document are reproduced

drawing No. 2 is not and this document does not cotain the names to be affiuxed

which Summers assumes to have been on a separate list.

Mr. Peppercorn's K1 Class. 32-4

Colour photo-feature: No. 62001 at Darlington; No. 62011 at Alnwick

with passenger train for Alnmouth; No. 62052 near Glenfinnan with passenger

trai for Mallaig on 21 June 1960; No. 62006 inside Alnmouth terminus in 1965

(David Lawrence); No. 62051 on express near Chelmsford in July 1959 (Alan

Chandler); No. 62052 near Lochailort on 21 June 1960; No. 62031 at Fort William

on passenger train which included an insulated container and a fish van (G.

Pratt)

John White. Remembering the Porthcawl Branch. 35-7

Black & white photographs are all by author. The Porthcawl branch

originated as a horse tramway to convet coal from Tywith to the harbour at

Porthcawl. It was called the Duffryn Llynvi & Porthcawl Railway and had

become part of the GWR by 1873 which constructed a new junction with the

main line at Pyle. After WW1 Portcawl grew into a holiday resort, but railway

trffic fell in the 1960s and the line closed on 9 September 1963, Illustrations:

No. 6435 on 14.30 railmotor being propelled out of Porthcawl for Pyle; panorama

of Porthcawl bleak station with its archaic gas lamps; No. 6435

at Pyle with 17.10 service from Porthcawl on 28 August 1963; No. 6434 at

Tondu with 13.40 service to Porthcawl on 8 September 1961; No. 6435 arriving

off Tondu branch at Pyle with 13.27 to Porthcawl on 28 August 1963; Nottage

Halt with No. 6435 arriving on 26 June 1963; Porthcawl station on 7 September

1963 with No. 80133 on 18.40 to Swansea High Street, No, 6434 on 18.55 to

Pyle and Cross Country dmu on 18.30 to Newport High Street

Brian Topping. Through Summit Tunnel. 38-41

Fireman's (steam locomotive not fire fighting sort) experience of

working through the tunnel. Writer was a passed cleaner working at Bury and

describes his initial experience of working through Summit Tunnel on a Crab

2-6-0 No. 42730 when he travelled out on tthe cushions to Sowerby shed where

he bparded the locomotive and ran light to Mytholmroyd to take over a freight.

8F runs through Bury Knowsley Street (Ray Farrell); 8F No. 48295 on a coal

train passing Class 4 2-6-4T No. 42484 on freight in Bury on 26 April 1965

(Ray Farrell); Sowerby Bridge shed on 10 September 1961; WD 2-8-0 No. 90181

exits western end of Summit Tunnel on 13 December 1963 (Ian G. Holt);; Jubilee

No. 45717 Dauntless on Liverpool to Newcastle express heads towards

Sunnit West Tunnel on 21 December 1960 (Ian G. Holt); Crab No. 2310 exits

Wateerbutlee Tunnel (D. Ibbotson); 2P 4-4-0 No. 40684 leaving Bury for Bolton

on ordinary passenger train on 8 April 1959;

Alistair F. Nisbet. The end of South Western steam. 42-8

From Waterloo and via Bsingstoke: broad survey with classes liable

to be found on pssenger services. Illustrations (all by author and with two

exceptions all in in colour: all Pacifics in rebuilt forms) West Country

No. 34004 Yeovil on 17.30 to Bournemouth leaving Waterloo on 31 March

1967; down Bournemouth Belle hauled by Merchant Navy No. 35005

Canadian Pacific on 26 August 1964; Batttle of Britain No. 34089 602

Squadron having brought in empty stock into Waterloo on 1 June 1966 (black

& white); No. 35008 Orient Line backing into Waterloo to

power 08.30 to Weymouth; No. 80140 bringing empty stock into waterloo passing

Vauxhall on 8 March 1964; No. 35030 Elder Dempster Lines,

80015 and 82029 in Waterloo engin dock on 5 April 1967 (b&w)

Philip Atkins. An Edwardian locomotive quadrille.

49-57

The links in locomotive design between the Midland Railway, the North

Eastern Railway, the Great Central Railway and the North British Railway.

The key person in this was Walter Mackersie Smith and his son, John William

Smith. W.M. Smith was a pioneer in the use of piston valves and

took out Patents. NER 2-4-0 No. 340, a two-cylinder compound was so-fitted

in 1888. In 1894 an inside cylinder M1 4-4-0 No. 1639 was fitted with piston

valves. Neverteless, the NER was slow to adopt piston valves: only the final

two S class 4-6-0s were fitted and many of the T class 0-80s were built with

slide valves. he Midland Railway was much quicker when John Smith moved to

Derby at Johnson's behest and the 1892 series of 4-2-2 were equipped with

piston valves, as were all new 4-4-0 designs, but freight locomotives were

not equipped until 1911 with the prototype Claa 4. On the Highland Railway

the trial by Jones on the Loch class was a failure and within four yeats

had to be replaed by slide valves.On the Great Central Railway Pollitt fitted

the 11B class 44-4-0 with piston valves and on the NBR Holmes adopted them

on the 317 class. Illustrations: NBR Reid 4-4-2 No. 870 Bon-Accord on the

13.55 Edinburgh to Perth (and Inverness) at Waverley c1909; 3CC 4-4-0 No.

1619 (3-cylinder compound) at Scarborough; Johnson 3-cylinder compound No.

2631 with bogie tender at Derby Works; 4-2-2 No. 2601 Princess of Wales

in grey workshop livery at Birmingham New Street in late 1899; Pollitt

Great Centrl 4-2-2 No. 971 at Manchester Central; MR 4-4-0 No. 999 (colour);

NER 4-4-0 R1 class No. 1238 (caption states that photograph reproduced appeared

in Locomotive Mag., 1909, 15,

page 73 (not quite so Backtrack image is straight elevation, whereas

Locomotive Mag. is three-quarter profile!); Robinson Director class

No. 430 Purdon Viccars at Gorton Works in 1913; NER V class 4-4-2

No. 532 in November 1903; GCR 4-4-2 No.1092; NER Class S 4-6-0 on freight

train at Dalton Bridge on 19 April 1922; GCR 4-6-0 Class 8B No. 1069 at head

of train of fish vans (posed photograph); Class 8A 0-8-0 as LNER No. 6139

on empty mineral train at Rugby in August 1925; proposed Johnson Midland

Railway 0-8-0 (side elevation diagram); proposed Reid North British Railway

0-8-0 (side elevation diagram); GCR 0-8-4T as LNER No. 6173 on March engine

shed; NER 4-8-0T as LNER No. 1353 on Darlington shed on 22 July 1934 (W.

Rogerson); restored 4P compound No. 1000 at Nottingham Victoria on RCTS East

Midlander on 11 September 1961; GNR (I) V class compound No. 85 Merlin

leaving Bangor (Ireland) for Belfast on 15 May 1989 (colour: D.W. Mosley).

See also letter from Mike Wheelwright on page 189

Still more men at work Paul Aitken. 58

Colour photo feature of permanenet way workers (platelayers to ancient

Kevin; gangers in the captions) in their high visibility orange clothing

at work: at Sheffield on 12 July 2000 shovelling ballast on modern concrete

sleepered track to adjust the angle of elevation or cant; Dent station on

18 July 1993 members of gang pushing trolley along track; Crossmyloof on

4 July 1993 unloading ballast from hopper with clouds of dust (Kevin's eldest

daughter loves trains but hates the dirt which sometimes comes home on her

husband's clothing from being a civil engineer working on railway projects);

Shawlands station on cold 27 January 1996 with ganger dropping salt on slippery

station platform (West Runton station has more salt than on the beach); King's

Cross station on 29 July 2003 with man on a light ladder cleaning the windows

of an HST power car. More of these watching men at work (but long after the

soft hats and cloggs days) pictures see Volume 30

page 562 and still more fron references thereat

Jeffrey Wells. Life, death and other matters - The Great

Western Railway in 1870 - Part Two. 59-61

Part 1 see previous Volume page 714.

Illustrations: Pembroke Dock station; Neyland station in 1933; Birmingham

Snow Hill station with Birminham Corporation trams in Colmoe Row; Slough

station; Awre station; Gresford station c1907. John C.

Hughes (letter p. 189) objects to phrase :90% of population lived in

abject poverty even when Wells is clearly peturbed at the absurd lengths

which the railways made to cosset the Royal Family

Readers' Forum 62

Lesser London. Graham Smith

The upper photograph at Farringdon Station on p689 of the November

issue of was almost certainly taken during the evening peak in June 1978

- despite the very few passengers visible! The seated passenger is reading

the Evening Standard (or was it The New Standard by then?)

for which the early edition did not appear on the streets until lunchtime.

The peak hour through passenger trains between the Midland line and Moorgate

were restricted for many years to just three or four trains during each peak

in the direction of the traffic flow, with appropriate ECS working in the

opposite direction. Latterly, these were usually all stations workings between

Luton or St. Albans and Moorgate. The former peak hour service to and from

the Great Northern suburban stations was considerably more substantial, but

that had ceased several years earlier when the service was diverted via the

former Northern City Line.

Platform 4 at Farringdon station would then only be used by passengers for

the three Midland Line slow trains during Monday to Friday evening peak -

the platform would have been closed off at other times of the day. With regular

Metropolitan/Circle Line trains from Platform 2 to King's Cross St. Pancras

and more frequent, often semi-fast, trains from St. Pancras to St. Albans,

Luton and Bedford, the use made of the three through slow trains to St.

Albans/Luton, especially from King's Cross Met (Pentonville Road), Farringdon

and Barbican stations was latterly not very substantial. The trains were

perhaps more popular for passengers joining at Moorgate. The presence of

a London Transport official is to ensure train doors were closed properly

before departure and also collect tickets from any passenger who might have

chosen to travel locally to Farringdon from Moorgate or Barbican by the BR

train. When DMU operation was first introduced on the St. Pancras-Bedford

suburban services from January 1959, it was found that the bodies on the

Rolls-engined units (with epicyclic gearboxes) allocated were slightly wider

than previous standard DMUs, and earlier non-corridor suburban coaches. This

would have been a safety hazard if it were necessary to evacuate a Moorgate

train on the steeply-graded curve on the section of the line between Kentish

Town and King's Cross Met, which passes beneath St. Pancras station, as the

tunnel wall clearance would not permit the train doors to be opened. As a

result, the Midland Line trains to and from Moorgate remained worked by

loco-hauled suburban stock until the early 1970s (retaining some steam haulage

until 1962), then by Cravens-bodied DMUs made redundant by line closures

elsewhere. Subsequently, a series of unexplained fire incidents resulted

in the replacement of the Cravens units by a miscellany of DMU stock with

narrower bodies, from elsewhere -; hence the 'Llandudno' destination display

visible in the photograph.Stephen A. Abbott seeks to explain

the "unexplained" fire incidents.

Eventually, electrification of the Bedford-St. Pancras suburban services

in the early 1980s changed everything and Platforms 3 and 4 at Farringdon

saw regular, all-day passenger train services.

Lesser London . Andrew

Colebourne

The picture of Bow station on p686 of Backtrack must have been

taken before November 1939 when the trams in Bow Road were replaced by

trolleybuses. According to http://www.disused-stations.org.uk/b/bow/ the

train service was suspended in May 1944 because of bomb damage but the station

remained open, served by a replacement bus service, until one month later

when a V1 flying bomb severely damaged the station buildings, resulting in

the demolition of the upper storeys of the central block.

The apple advertisement is mentioned in the caption

to the picture of Mildmay Park station. I think it dates the image to

1975/76 when there was an 'English Apples and Pears' promotion. There was

a Routemaster bus that was painted in an overall advertising livery as part

of that promotion. One of the routes it worked was the 171 which ran past

the disused station.

Great Western eight-coupled tanks. Michael

Horton

Rer picture of No.5237 on p675 (November), I can confirm, that the

said locomotive was spotted at Wolverhampton Works on 15 April. I believe

that date of the photograph was 1 April 1962, as the same shot was published

in another magazine giving this information. It was very unusual for this

Class of locomotive to appear at Oxley, for the reason that the article stated

- small coal bunker. How it got to Oxley is a mystery? It could have been

towed to Oxley: it may have worked unaccompanied on an incoming freight,

or it was assisting another locomotive on a similar freight, but I believe

that it was towed to Oxley, as part of a freight. If it was towed to Oxley

alone, why did it not go direct to the Works? Maybe someone has got more

information on this issue and I shall be very interested to find out the

full facts.

The West Coast Main Line electrification

. Stephen G, Abbott

To add to Alan Taylor's excellent review (November) the WCML scheme

had its shortcomings. After resignalling Manchester-Styal-Crewe the next

phases, the lines through Stockport, Liverpool-Crewe and Crewe-Nuneaton used

numerous, mostly pre-existing, signal boxes as did the Potteries and Northampton

loops. Presumably this was to trim costs in the face of threatened curtailment

of the scheme, later sections resuming the practice of large power boxes.

Islands of local control remain to this day on the Liverpool line and at

Stockport -; the large LNWR boxes there stand testament to a missed

opportunity.

With lack of foresight there was much waste: far too many sidings and yards

were wired, a district electric depot built at Rugby soon became redundant

as few trains started or terminated there, Castlethorpe station north of

Wolverton was rebuilt then closed in September 1964 (the platforms survive)

and the mail facilities at Tamworth were largely wasted as the West Coast

TPO was diverted via Birmingham New Street in March 1967, interchanging traffic

there instead. On 18 April 1966, en route back to college in the Wirral,

I travelled into Rugby from Market Harborough on a line sadly axed a few

weeks later, before enjoying a high-speed electric run to Crewe - which made

one feel that there was a future for railways after all. See

also letter from Robin Leleux on p. 190 on how he became a late user

of Castlethhorpe statin when the locomotive hauling the train he was on shed

its motion.

The West Coast Main Line electrification.

Robert Day

Re Alan Taylor's article in the November issue, as my late father

was engaged in much of the signalling work connected with the electrification

and the conversion to colour light signalling. Based in the London Midland

Region signalling drawing office on Nelson Street in Derby, he produced plans

for, and then went out on the ground to instal and test, many of the schemes.

At various times he worked at Macclesfield, Stafford and Euston, putting

in full weekends, especially over the notoriously hard winter of 1962-63.

Taylor's article omits to mention that!

My father's experience also showed up the reality behind the four-year delay

in obtaining Parliamentary approval for the northern extension of electrification

from Weaver Junction to Glasgow. Although the engineering study started in

1966, as far as my father was concerned, no new work came his way for

electrification; rather, he was asked one night in 1966 to put in an hour's

overtime, to do a rush job on the proposal to close the Midland main line

through the Peak from Matlock to Chinley and single the line from Ambergate

to Matlock. "In an hour's overtime" he later said "I put fifty blokes out

of work, and that was just the signalling staff." This upset him. His managers

were unable to give him any reassurance about the likelihood of more work

putting the modernised railway in, but suggested that there would be more

work in taking old railway out. He accordingly could see no more future in

railway work and left BR later that year to take his skills to the construction

industry.,

The GWR in Wirral. Mike Lamport

My old chum Robin Leleux's response to the quest for information about

this venerable cross-country train in the November edition prompts me to

add the following. Between 1958 and 1960 while my father was station master

at Selling in Kent we made regular family rail trips from there to visit

his parents who lived in Godalming in Surrey. Normally, these trips to the

see the grandparents were made via London but, on one particularly memorable

occasion, Dad announced that this time we were going take 'the Continental'

or 'Conti' as the local rail staff in Kent called it ( It did have that Dover

portion after all) from Canterbury West. How exciting the prospect sounded

to this ten-year-old fan with visions of one of Mr. Bullied's Pacific's sweeping

us through the hop fields and into that uncharted territory beyond Tonbridge.

The reality, as I stood on up platform at Canterbury West platform craning

my neck to see our engine coming down the line from Margate, was something

of an anti-climax. Instead of Pacific, the locomotive was a rather nondescript

Maunsell UI Mogul. The train itself, however, made up for this by being formed

of a number of smart carmine and cream coaches which, from someone brought

up on a diet of Southern green, made it feel special after all. Years later,

when Dad returned to his Surrey roots as assistant station master at Guildford,

he still spoke of the 'Conti' while his staff there, as Roger correctly reported,

called it 'the Birkenhead'.

The Birmingham West Suburban Railway.

James Lancelot

It was a pleasure to read Geoffrey Skelsey's thoroughly-researched

article on the Birmingham West Suburban Railway (November). The figures he

quotes tell a sorry tale; but I am not sure that they altogether allay the

disgust I felt (and still feel) at BR's treatment of the route.

At its lowest ebb, my local station of King's Norton was served by a mere

five trains a day on Mondays to Fridays -; two from Redditch and one from

Worcester and beyond into Birmingham in the morning and two to Redditch in

the evening. This was against a background of the recent introduction of

one-man buses on the parallel route which did not give change and which were

delayed both by the need for the driver to sell tickets and the extra congestion

caused by city-centre reconstruction. Passengers who might have been tempted

to defect from the bus to the train were dissuaded by the closure of the

entrance to the station from Cotteridge which otherwise would have been

convenient for the local shops and bus stops (today, this is the principal

entrance to the station). Such a situation, combined with the lack of any

attempt to tap into potential traffic from Longbridge, Cadbury's, the Queen

Elizabeth Hospital, the University and the preparatory schools in Edgbaston

leads one to suspect that BR were not interested in keeping the local service

alive -a suspicion strengthened by their proposal to close the Redditch branch

and close the BWSR stations no sooner than Redditch had been nominated a

new town. The transformation of the service in 1978 was a wonderful step,

but the potential had been there long before.

Harry Pitts and the Aldersgate Explosion . Andrew

Colebourn

In the caption to the picture of the locomotive Edmund Burke on p697

of the November issue; the train is approaching Farringdon station on the

outer rail, not Aldersgate. The location can be seen in the background of

the picture on p695.

Harry Pitts and the Aldersgate Explosion.

Michael J. Smith,

The electric train in the photograph on p694 is of District rather

than Metropolitan stock. At this time both companies shared the operation

of the Inner Circle.

'Rather unprincipled persons'. Frank

Walmsley

Re A.J. Mullay's article on Ministers of Transport in the

September/October issues made compelling reading. Barbara Castle did a long

stint as MP for Blackburn. Scouts at Queen Elizabeth's Grammar School were

grateful to her when she overturned a British Rail refusal to stop an express

at Preston so allowing the troop and equipment to journey to Scotland for

an annual camp.

In her autobiography Fighting all the way (MacMillan 1993) Barbara

described her appointment as Minister of Transport. "The task I faced was

gargantuan. In pleading with me to accept the post Harold Wilson said to

me 'Your job is to produce the integrated transport policy we promised in

our manifesto', adding characteristically 'I could work something out myself,

given half an hour'. This was an oversimplification de luxe." In the same

paragraph she went on to explain that the department had no tradition for

planning transport as a whole. Its work was compartmentalised under three

deputy secretaries dealing with highways, urban olicy and a miscellany in

which railways were ped with ports, shipping and nationalised roa rt. "It

seemed a chaotic system to me."

The Beeching Report was waiting for her on arrival. Closures had begun and

there was uproar among Labour's rank and file which had always been pro-rail.

Barbara was determined not to allow market forces to destroy a railway system

on which so many people were dependent, to say nothing of turning traffic

on to overcrowded roads. Chapter 15 'Full Steam Ahead' should be made

compulsory reading for all Ministers of Transport on the day of their

appointment. ,

Winter wonderland. David Rodgers. rear cover

8F 2-8-0 No. 48191 in highly polished state hauls short Topley Pike

to Buxton freight in light snow on 24 February 1968. See previous volume

for letter from Alan Eatwell on how No. 48191

was kept in toy railway condition and further portraits

of this beautiful locomotive

LMS Stanier Class 3 2-6-2T No.40125 takes it easy in the sunshine at Willesden locomotive depot in the mid-1950s. Trevor Owen. front cover

Looking back to September 1951. Jeffrey Wells. 67

Guest Editorial based on content of Trains Illustrated for

that month. At least one of the items is in Steamindex

(the initial ffull description

of the BR Standatd Class 4 2-6-4T). His reference to the extinction of

the Southern D1 class relates to the Stroudley 0-4-2T not the Wainwright

4-4-0. It is a good reminder of Trains Illustrated (a few copies of

which are usually available at Weybourne Station).

Freight through Warrington. Tom Heavyside. 68-9

Colour photo-feature:Class 40 No. 40 020 hauling empty mineral wagons

passing eastbound under Bank Quay station with huge Unilever soap and detergent

factory dominating scene on 18 September 1980; Transrail Class 56 No. 56

127 passing Warrington Arpley with merry-go-round coal train from Yorkshire

to Fiddlers Ferry on 25 June 1996; English Electric Class 20 Nos. 20135 and

20 065 passing Warrington Arpley with merry-go-round coal train on 27 February

1987; Class 40 No. 40 172 on mixed freight between Walton Old Junction and

Warrington Arpley on 19 September 1980; Class 85 No. 85 106 on down Freightliner

near Winwick Junction on 12 July 1990.

Bruce Laws. Les Beet:: extracts from a steam locomotive

driver's log book - Part Two. 70-5

Part 1 in previous Volume beginning page

753. Les was frugal in his use of log books and this led

to him over-writing the earlier entries with later information which created

difficulties in transcription, also during the period in which he was a passed

fireman there is no certainty whethr he was firing or driving. The period

includes WW2 when Nottingham suffered eleven major raids - targets being

the Boots factory, the loacl power station, the LMS works and the ordnance

factory at Ruddington. The route of the former Great Central is noted as

it strode southwards (part bing incorporated into the preserved railway,

but the route through Leicester was obliterated: the author records its loss

to what might have been a more viable HS2. Illustrations: O4/7 No. 63675

2-8-0 arriving in Nottingham Victoria (first four and last all by Stuart

Grimwade); former LMS 8F 2-8-0 within Notttingham Victoria; B1 4-6-0 No.61141

taking Grantham line at Weekday Cross Junction with a freight in 1966; Viaduct

at Weekday Cross; exterior of Grantham station on 28 May 1950 (A.C. Roberts);

O1 2-8-0 No. 63678 at Colwick Woods on long mineral train in July 1963; O2/2

2-8-0 No. 63943 on Grantham shed on 29 July 1963; and Class 5 4-6-0 No. 44835

takes road for Leicester at Weekday Cross in 1966. Letter

from R. Lloyd Jones notes that Beeching excommunicated Rugby from Leicester

(not as implied herein) and that Great Central Railway went over Midland

Railway rather than over it at point show on map. See also

long letter from Michael Elliott on p. 317 mainly on what was demolished

to make way for Nottingham Victoria and references to other material on this

significant City Centre station.

Jeffrey Wells. Private and public opposition to nineteenth century

railways. 76-81.

Newcastle & Carlisle Railway: objection by Charles Bacon of Styford

and his son, Charles Bacon Grey. Also problem of crossing Hadrian's Wall

at Greenhead and Gilsland (where care was taken to protect the structure).

The Newcastle Courant 17 January 1829 published a notice objecting

to the railway. The Dalton & Barrow Railway was planned without consideration

for the ruins of Furness Abbey, but prior to construction to avoid litigation

the line was adjusted to avoid the ruins and these became a source of excursion

traffic. The Manchester Times and Gazette 11 September 1846 reported that

500 people had visited the ruins. Dorchester was surrounded by ancient monuments

and both the LSWR and the GWR had to take care not to cause too much damage:

the latter was forced to tunnel under Poundbury Camp. The railway between

Blackburn and Hellifield was forced to construct a tunnel to protect the

vista from Gisburne Park owned by Lord Ribblesdale who had cut the first

sod. The Blackburn Standard reported on progress on the line. Eton College

was anxious to keep the Great western at a distance from its ppupils but

changed its stance when they were invited to attend Queen Victoria's Coronation

on 28 June 1837 and a special train was provided. Ancient sites transgressed

included the castles at Berkhamstead, Castlethorpe, Berwick upon Tweed and

Flint. The City wall at York was breeched and Cheltenham station was built

over a tumulus. Illustrations: Gilsland station, Dorchester GWR station

with steam railmotor (railcar) caption staes June 1895. but railmotors not

introduced then (1905?); Furness Abbey station; southern portal of Gisburn

Tunnel; western portal of Shugborough Tunnel; Windsor station Southern Railway

frontage c1925 (Sir William Tite architect); Berkhamstead station with Grand

Union Canal probably in Victorian period; Castlethorpe station viewed from

road to Pottersbury; arch built into York's City wall on 5 October 1991 (T.J.

Edgington); blue No. 46241 City of Ediburgh above former stone circle

at Shap Wells with 10.40 Euston to Carlisle on 3 June 1950 (Eric

Bruton)..

Edward Gibbins. The fate of the Stainmore Route - Part

Two. 82-8

Part 1 in previous Volume beginning page 739. The

general thrust is that various marginal bodies, such as ramblers, protacted

the closure process through their ill-considered interventions. The Transport

Users' Consultative Committee held meetings in Leeds, Preston and Newcastle.

James Boyden, the MP for Bishop Auckland was a forceful objector. Much was

made of the extra mileage imposed on freight, but those directly involved

made light of this (many already used motorways in preference shorter routes

on ordinary roads, Illustrations: Class 3 2-6-0 No. 77003 and Class 4 2-6-0

No. 76049 cross Belah Viaduct on farewell special on 20 January 1962 (colour:

Gavin Morrison); Class 3 2-6-0 No. 77002 and BR Standard Class 4 2-6-0 cross

Smardale Viaduct with eight coach Blackpool express in late 1950s (Cecil

Ord); J21 0-6-0 No. 65033 on RCTS special at Ravenstonedale on 7 May 1960

(colour: Gavin Morrison); No. 76048 on coke empties leaving Smardale Viaduct

on 31 August 1956 (J.F. Davies); BR Standard Class 2 2-6-0 Nos. 78017

and 78013 on short mineral train at Stainmore Summit on 18 August 1958 (Gavin

Morrison); Ivatt Class 2 2-6-0 No. 46482 at Stainmore Summit on 25 July 1952

(T.G. Hepburn); J21 0-6-0 No. Nos. 65089 and 65047 at Stainmore Summit on

25 July 1952 (T.G. Hepburn); BR Standard Class 4 2-6-0 No. 76049 and Ivatt

Class 4 2-6-0 near Stainmore Summit with a Blackpool train in

late 1950s (Cecil Ord); No. 77003 and 760499 at Kirkby Stephen on last day

special on 20 January 1962 (colour: Gavin Morrison).

Jeffrey Wells. The Ambergate Junction complex. 89-91

Former triangular junction but now reduced to a halt on the Matlock

branch (all that remains of the former main line to BBuxton and Manchester.

Newspaper accounts from Leeds Mercury and Derby Mercury relate

to various openings from the original station on the North Midland Railway

main line, through to the branch to Matlock, the extension to Buxton and

the curve giving direct communication between the Buxton line and the route

towards Chesterfield, The station buildings were designed by Francis Thompson,

were of sufficient substance to justify their movement stone by stone to

accommodate the Manchester branch and were then Cromwelled by British Railways

(they were in the Jaacobean style rather than the cardbord box style favoured

at that ime). Illustrations: original station (engraving); MR 4-4-0 No, 251

with five clerestory coaches on express heading for Derby; 4F No. 4420 with

another 4F on empty minerals train from Matlock to Derby (date in caption

clearly wildly incorrect as Midlamd running-in board and gas lamps still

visible; junction of two main routes; D45 class on express from Manchester?

on 22 October 1966.

90 Years of the Railway Correspondence & Travel

Society.. 92-5

2018 marks the 90th anniversary of the founding of the Railway

Correspondence and Travel Society, believed to be now the largest UK railway

society and possibly only eclipsed in its membership numbers over the years

by the Ian Allan Locospotters' Club, albeit that the latter was aimed at

a vastly different audience. The text minus the excellent illustrations is

reproduced on RCTS page

The shores of the Utmost West .Dick Riley. 96-9

Colour photo-feature: No. 6029 King Edward VIII at Teignmouth

with express (leading vehicle of which was formed of a Centenary coach in

carmine & cream livery on 1 July 1957; No. 5069 Isambard Kingdom

Brunel on ordinary passenger train crossing Royal Albert Bridge approaching

Saltash on 28 August 1961; Castle class No. 5055 Earl of Eldon departing

Teignmmouth on up Devonian on 17 July 1958; No. 5059 Earl of

Adwyn on up Torbay Express; Earl of Plymouth on down Royal

Duchy on the steep climb to Dainton summit on 1 July 1957; No. 6965

Thirlestaine Hall on up stopping train on sea wall at Dawlish on 14

July 1958; No. 6010 King Charles I on up express formed mainly of

carmine & cream stock on 14 July 1958; No. 1025 Western

Guardsman with down Motorail service on sea wall near Dawlish

on 6 September 1973: see also letter from Mark Evans on

p. 253.

Looks can be deceptive [LMS Class 3 2-6-2T loocomotives; ;both Fowler

& Stanier]. 100-2.

Colour photo-feature: No. 40026 (with condensing gear) at St. Pancras

on empty stock duty; No. 40024 (with condensing gear and ex-Works condition)

at Moorgate in 1959 with Metropolian F stock (with oval motorman's windows)

and brown livery T stock (J.G. Dewing); Stanier No. 40164 at Blackpool Central

shed with rebuillt Patriot No. 45530 Sir Frank Ree and Class 5 No.

44737 alongside in October 1959; No. 40150 at Thurso on

12 July 1960 (C. Hogg) see Editorial corriegenda p. 189

both date should be 16 April 1960 (hence lack of leaves on trees and photographer

was Patterson see also letter from John Macnab on p.

253; No. 40202 at Llandudno Junction with through coaches for resort

in August 1962; No. 40138 at Coventry on station pilot duties

— see letter from Leonard Rogers on p. 254; No,

40004 at Cricklewod shed in May 1955 (Trvor Owen) [KPJ Wot no Delph Donkey?];

Western waysides: a selection of stations on Great Western lines..

103-5

Black & white photo-feature: 45XX on short branch freight from

St. Ives passing Carbis Bay station on 23 August 1949 (Eric Bruton); 2-4-0T

Metro tank? on local train calling at Fladbury in Edwardian times with young

ladies travelling towards Pershore and perhaps Worcester; Bugle

station on Newquay branch Not Bugle, but Roche see

Editorial corriegenda p. 189; Chipping Norton Junction station (pre-1909

when renamed Kingham); Perranporth station with two? steam railmotors (railcars)

c1912 (note advertisement featuring four-funnel liner);

Llansantffraid station on Llanymynach-Llanfyllin branch

with Class 2 2-6-0 No. 46510 arriving on passenger train on 22 May 1964

see Editorial corriegenda p. 189; Rollright Halt (image

suffering from scanning defect); and St. Agnes station, possibly at same

period as Perranporth image

Alistair F. Nisbet. Poor Postal services to Scotland. 106-11

Text and images out of sync. Text refers to the Postmaster General

from the City and Royal Burgh of Perth in 1846 and 1847 and 1848 on delays

to Her Majesty's Mail. The Kelso Chronicle of 28 October 1853 complained

that letters for Kelso and Hawick only went to Melrose once per day. The

Aberdeen Free Press reported on 1 July 1886 on an improved service

for letters and newspapers to reach Inverness, Dingwall and Strome Ferry,

and even Kirkwall in Orkney on the same day. On 17 February 1871 the Dundee

Chamber of Commerce compllained to both the GPO and the Caledonian Railway

about the late arrival of the Scotch Limited Mail. The Dundee

Advertiser reported on 2 July 1885 that weekend mail for Dundee and Aberdeen

would be improved by trains leaving Euston at 20.30 and with a corresponding

up train leaving at 14.04: these were known as the Up and Down Specials.

Both Aberdeen and Dundee sought faster mails: the latter argued that

the East Coast Route was better suited for faster transport to many places

in the East of England. William Monsell when Postmaster General met delegaions

from the north of Scotland and studies were made to improve transits. Tne

North British Railway had an especially acrimonious relationship with the

Post Office with respect to costs, times, delays to other services and the

employment of messengers to carry the mail (and the fares paid). Illustrations:

St. Andrews station,; Cupar station long before it was selected in preference

to Leuchars as a railhead for St. Andrews mail following the ill-judged closure

of its railway; D34 No. 62485 Glen Murran at Dundee Tay Bridge; J37

No. 64620 at Dundee West in 1963; Perth c1912 with 17.45 up postal hauled

by 139 class 4-4-0 No. 117; Aberdeen General; Wick station in HR

period;

David Pearson. County Donegal Railways Joint Committee.

112-17.

States that County Donegal Railway was the largest narrow gauge network

in the "UK" (presumably the UK which ceased to exist upon the cession of

Donegal to the Republic of Ireland). The article is mainly an examination

of the sources of finance for a collection of railways which appeared to

be short of finance and the involvement of the Midland Railway in manipulating

the financial structure of other railways by purchasing shares in them in

an attempt to channel traffic onto its trunk lines, Thus, the Midland &

South Western Junction, Hull & Barnsley and even the West Cornwall Railways

are all mentioned as part of the web centred on Derby. The captions to the

photographs (all black & white) are an integral part of the presentation:

4-6-0T Foyle at Stranorlar and 2-6-4T No, 8 Foyle (formerly

Staphoe) at Donegal Town on 29 June 1950 (caption implies influx of

Midland capital enabled the big engine policy); 2-6-4T No. 2 Blanche

with CDJR climbing through Barnesmore Gap on long mixed train including

substantial bogie coaches in May 1956 (caption notes substantial nature of

train) (photograph: E.S. Russell); coaches at Strabane on 13 June 1964 (T.J.

Edgington) (coaches were intended for export to USA, but finance failed to

arrive); 4-6-4T No. 11 Erne at Londonderry Victoria Road on 13.35

for Strabane on 24 April 1951 (T.J. Edgington) (caption eulogizes over

superlative machines, but fails to note lightness of its train); Class 5

2-6-4T No. 4 Meenglas waits at Stranorlar on 17.52 freight for Donegal

on 6 August 1959; Class 5A No. 3 Lydia at Killybegs c1935; substantial

bridge across River Finn on Glenties branch on29 June 1950; diesel railcar

No. 16 at Stranorlar on 07.40 Killybegs to Strabane working (T.J. Edgington).

There is also a map of the system

The Black Pugs of Ayrshire. Photographs by David Idle; text by John Scholes.

118-19.

Colour photo-feature of Andrew Barclay & Co. mainly 0-4-0ST saddle

tank engines working at the collieries to serve the Damellington Iron Co.:

0-4-0ST (NCB No. 19;: WN 1614/1918 propelling Jubilee skips towards Leight

tip on 26 April 1973; another 0-4-0ST No. 21 (WN 2284/1949 at Leight tip

on 27 April 1973; No. 16 (WN 1116/1910) at Mauchline Colliery in 1974; No.

19 again en route to tip on 27 April 1973; and 0-6-0T No. 24 (WN 2335/1953)

with Giesl ejector near Waterside washery on 27 April viewed from cab

Miles MacNair. Tackling the gradient: John Fell and

some locomoive/cable hybrids. Part Two. 120-4.

Part 1 in previous Volume beginning page 710.

John Barraclough Fell developed his eponymous

central rail system for the Mont Cenis Pass crossing of the Alps. Ganta-Gallo

railway in used former Mont Cenis equipment to serve high altitude coffee

plantations in Brazil. From 1883 these were replaced by Baldwin 0-6-0Ts which

only used the centre rail for braking as on the Snaefell Mountain Railway.

The Rimutaka Incline in New Zealand was the longest and most famous application

of the Fell system. Tomasso

Agudio rope-worked system for Sassi-Superga tramway. The

Henry Handyside system for tackling

very steep gradients involved a locomotive which could be clamped to the

rails and haul its load up with a steam powered winch.Illustrations: Fell

centre rail diagram; plan of Gouin Mont Cenis locomotive; Cail Mont Cenis

locomotive (engraving); Manning Wardle works photograph of WN 377/1872 locomotive

for Fell system on Ganta-Gallo railway in Brazil: Avonside Rimutaka locomotive

after rebuilding (outside Stephenson valve gear employed); Neilson &

Co. Rimutaka locomotive with external Joy valve gear; Agudio rope-worked

locomotore for Sassi-Superga tramway; Handyside patent drawing from

Engineer, 1874 September; Handyside rail gripper; Fox Walker WN 284/1875

as per Engineer; Fox Walker WN 316/1875 as per Cromford & High

Peak trials; Fox Walker HPTE as supplied to Royal Engineers and Dick, Stevenson

system as installed at Provenhall Colliery in Glasgow in 1875.

Readers' Forum 125

Secondary considerations. Leonard

Rogers

The train seen in Trevor Owen's photo at Greenock on p.751 is bound

for Wemyss Bay, not Gourock. The loco shed at Ladyburn is seen in the left

centre of the picture, with wagons visible at the coaling stage, below the

Wemyss Bay train. The Gourock line is beyond the far side of the shed yard,

heading for Greenock Central station, the two lines having parted company

to the west of Port Glasgow, off camera to the right.

Robberies on the Rails. Leonard

Rogers

The date for the photo of 60052 at Thornton on p.731 will not be 1952,

since its cab sides bear their "not south of Crewe" yellow stripes. These

were applied in August 1964, in anticipation of the ban coming into effect

the following month, and the loco was withdrawn from service at the end of

December 1965.

Life, death and other matters - the

GWR in 1870. S. Tamblin

A small correction to your article in the December issue, p718 - the

view of Banbury station is facing south, not north. The station buildings

are on the west side of the line; the locomotive and two coaches are in the

bay added for GC line services.

Bushey water troughs in LNWR days.

Tim Birch

It was wonderful to see the Tice Budden photographs together with

the commentary by Ted Talbot in the December issue of Backtrack. They will

remind devotees of the LNWR, and introduce the uninitiated, to what an excellent

main line led to the north from Euston. The LNWR appendix to the working

timetable issued in January 1905 lists that 'DX' and tank engines were permitted

to take 50 loaded minerals (including brake van) between Tring and Willesden

or Camden and 60 empties. Interestingly, the number of loaded wagons that

could be hauled between Stafford and Tring or between Camden and Stafford

was 40. This was presumably in recognition of the gradients. May I take this

opportunity to tell your readers that the LNWR Society has an archive of

thousands of documents relating to the operation the company's services,

plus drawings of rolling stock and the infrastructure and many photographs.

New members are always welcome, and copies of many items can be provided

from the archive and study centre in Kenilworth. anyone interested is invited

to look at the Society's web site at Inwrs.org.uk

The Railway Mission. Dudley

Clark

Re article on the Railway Mission (RM) and its mission halls in the

November issue; as Archivist and Historian of the Mission he was pleased

when attention is drawn to the Mission. The mission was formed in 1881 when

the committee of the Railway Boys Mission decided to broaden its work to

include all railwaymen. At the time there were several other missions with

similar objectives and many of these subsequently became part of the RM.

The article confused the first meeting of the RM with the commencement of

the Bishopsgate branch of the Mission which was started circa 1890. Temperance

was not specifically a denominational issue; there were strong movements

within most denominations and it was also supported by Socialists such as

Keir Hardie.

The article quoted from the GER Magazine was written by Stratford

Goods Agent W.F.C. Bullivant who had been a member of the Stratford branch

of the RM from at least 1900 and particularly focuses on the involvement

of GER employees with the Mission. What became the Stratford branch had been

formed as the GER Servants' Christian Union in 1879. With reference to the

dates given for the building of mission halls I would draw attention to Liverpool

and Brighton. The 1896 date for Liverpool refers to the formation of the

organisation; the Liverpool branch consisted of many sub-branches which generally

met in the work place. There were eventually two mission halls, one near

Edge Hill and the other at Walton on the Hill. The earliest reference I have

for either hall is 1909. The Brighton branch was formed before the RM in

1876 and met on railway premises until a redundant Methodist church was purchased

in 1894. This continues as a place of worship today.

None of the London Termini ever had an adjacent RM mission hall and the branch

at the one major goods depot with a branch, Bishopsgate, met at their place

of work until the depot was destroyed by fire in 1964. There was a mission

hall at King's Cross, Culross Mission, which was built by the GNR. It was

never part of the RM and the missionary was provided by the London City Mission.

The downward trend in membership accelerated between the World Wars and continued

after WW2, but many branches left the RM to continue as independent churches.

Finally it is misleading to call St. Saviour's, Westhouses, a 'Railway Mission

church' as it was always part of the Church of England. Furthermore St. Saviour's

was not built on railway land; the site was provided by the Agent of the

Duke of Devonshire at a nominal rent and the building was entirely financed

by locally raised funds. Railway Mission is a registered charity in England

and Wales (1128024) and in Scotland (SC045897)

Les Beet You have credited the picture on p757 (December) of Ipswich Docks Lower Yard to Geograph whereas its actually 'Stuart Grimwade/ Ipswich Maritime Trust Image Archive'. Bruce Laws,

Worcestershire's Railways. Nick Daunt

Re article by Steve Roberts on Worcestershire's Railways' (October)

brought back happy memories, especially the illustrations. Sixty years ago

Worcester was a favourite venue for the group of rail enthusiasts to which

I belonged in my Birmingham school. A return ticket to Worcester was valid

on both the GWR line via Kidderminster and the Midland line via Bromsgrove.

In the outward direction we would always, for reasons which will become apparent,

catch a Birmingham Snow Hill to Cardiff train, consisting of, I think, six

corridor coaches hauled by a 'Hall' 4-6-0. This departed from the north end

bay at Snow Hill, a fact which probably limited the length of the train.

For us this was a 'real' express, although it has to be said that the coaches

were usually ex- GWR stock which had seen better days and the progress of

this 'express' was quite stately. We stopped at Stourbridge Junction,

Kidderminster and Droitwich Spa. The Black Country, through which we passed,

really was black in those days. There seemed to be a permanent pall of smoke

hanging over places such as Old Hill and Cradley Heath. How things have changed.

While I was waiting recently on Smethwick Galton Bridge for my Class 172

to whisk me to Kidderminster and the SVR, I actually saw a buzzard soaring

overhead! At Old Hill we would look out for the line branching off to Halesowen,

whence it continued as a joint GWR and MR line to Longbridge, making a connection

with the Midland's main line to the South West.

Our train would stop at Worcester Foregate Street, by-passing Shrub Hill.

It would then continue via Great Malvern, Ledbury, Hereford and Newport.

Foregate Street was considered far less interesting than Shrub Hill, so,

having alighted, we would catch the first available train for Shrub Hill.

This journey only took about five minutes and, as far as I remember, we were

usually hauled by a pannier tank.

Shrub Hill was a really fascinating station on which to spend two or three

hours. There was always some locomotive movement to watch and we could enjoy

an interesting mix of ex-GWR and LMS motive power. The highlights were always

the Hereford-Worcester-Oxford- Paddington services, hauled by one of Worcester

shed's 'Castle' Class 4-6-0s. In my experience an 85A 'Castle' was always

kept in immaculate condition. Castle names such as Berkeley, Dartmouth, Nunney

and Monmouth stick in my memory as well as No.7005 Lamphey Castle

which I remember being renamed Sir Edward Elgar in 1957 to mark the

centenary of the birth of Worcester's greatest son. There was also No.7007

which, because it was the last 'Castle' turned out of Swindon by the independent

GWR, was named Great Western. These Worcester engines very rarely

turned up in Birmingham. The most prestigious train of the day was the

Cathedrals Express (serving the cathedral cities of Hereford, Worcester

and Oxford), but I never saw that at Worcester since it departed quite early

in the morning and returned after we had gone home. I did see it at both

Reading and Paddington, however.

Worcester shed was always worth investigation. We regarded it as very much

as a rail frontier, with the possibility of seeing rare Welsh locomotives

which would never turn up in Birmingham (eg Churchward 2-8-0 tanks if you

were very lucky). On one occasion we went round the shed officially, with

the father of one of our group being the 'responsible adult', but I think

we may have 'bunked' the shed on another occasion. There was really no need

to do that because it was possible to get a superb panorama of the shed from

a path which overlooked it. On one occasion, I remember, we saw No.45500

Patriot standing in the yard. Another attraction was the 'vinegar

line', a branch which served the Vinegar works of Hill, Evans & Co. It

crossed a street by means of an ungated level crossing, where road traffic

was regulated by means of GWR lower quadrant signals. I hope the car drivers

understood what they meant!

All too soon it would be time to come home, so we would catch a local from

Shrub Hill to Birmingham New Street. This could be hauled by a 4F 0-6-0 as

in the illustration on p619, but 'Crabs', Ivat! Class 4 Moguls, Fowler 2-6-4

tanks or 'Black Fives' might turn up. Organising the day this way meant that

we had the wonderful experience of climbing the Lickey and, of course, we

always made sure we were in the last carriage, preferably the last compartment,

so that we could enjoy the pyrotechnics from the banking engine. Having arrived

at the chaotic slum which was the old New Street, we caught our buses home

in time for tea. A really good day out!

The Vale of Rheidol Railway. David

Pearson

Re picture spread on the Vale of Rheidol Railway. The VoR was not

the first 'privatisation' to take place. In 1967 agreement was reached by

BR to sell for the first time a complete railway. In using this phrase, I

mean as was the case with the VoR, a complete, entire statutory railway which

had become part of the BR network. The railway to which I refer was the Keighley

& Worth Valley Railway, incorporated by Act of Parliament in 1862 and

absorbed by the Midland Railway in 1886, but as much a statutory railway,

complete and entire, as was the VoR in 1989.

Shunting Dibles Wharf .John

Roake

You seem to have slipped into the same error that several

railway-orientated web sites have also done. The photographs in the December

issue of Backtrack were not taken at DIBBLES Wharf in Southampton, but at

DIBLES Wharf. I cannot tell you the vernacular pronunciation of the DIBLES,

but we in the corn trade always pronounced it with a hard "i". I traded corn

into there many times in my working life, where it was loaded on to boats

for exporting and even visited there on one of our lorries once to show support

for our lorry drivers and to watch operations. Tipping corn on to railway

lines covered in oil and coal dust did not strike me as the most appropriate

way to handle feedstuffs! ,

Book Reviews, 126

George Carr Glyn - railwayman and banker. David

Hodgkins. Wolfe Press (Amersham) Softback, 487pp. MGF *****

This weighty tome is a scholarly biography comprising 19 chapters,

60 illustrations, seven maps, an exhaustive bibliography and a comprehensive

index. It tells of the life of George Carr Glyn, 1st Baron Wolverton (1797-1873)

and covers all aspects of his life: family, education, business affairs and

his involvement as Member of Parliament for Kendal from 1847 to 1868. This

is a very serious historical record written in an easy to read style.

Much of the book concentrates on his banking activities as a partner in the

family firm of Glyn, Mills & Co., one of the largest private banks in

London. However, his involvement as Treasurer to the dock company responsible

for the construction of London's St. Katharine's Dock, which opened in May

1830, is also explained in great detail. More importantly, for readers of

Backtrack is the extensive coverage given to Glyn's involvement with railways

at home and abroad, especially with the Grand Trunk Railway of Canada. We

learn that in 1845 the bank had 110 railway companies banking with it, compared

with 22 in 1843. This was, of course, during the period of the 'Railway Mania'

and the author explains that some of the railways projected by the bank's

clients may not have come to fruition.

Glyn not only provided banking facilities for railway companies but became

actively involved with their management. For example from 1836 to 1841 he

was chairman of the North Midland Railway and he was instrumental in founding

the Railway Clearing House in 1842 but his greatest involvement was with

the London & North Western Railway (LNWR). In 1837 he became the second

chairman of the London & Birmingham Railway (LBR) and when that railway

was amalgamated with the Grand Junction Railway (GJR) and the Manchester

& Birmingham to form the LNWR in 1846 he became its first chairman. He

held that key position until his resignation in September 1852; thereafter

he remained as an active director for another decade and did not retire from

the board until 1870.

The background to the amalgamation which established the LNWR is explained

in great detail highlighting disagreements between Glyn and John Moss, Chairman

of the GJR. Glyn's prime role in protecting the LBR's interests with regard

to the proposed Trent Valley Railway, securing the Irish mail traffic and

keeping the Great Western Railway at bay on the LBR's western flank makes

for an interesting, if at times, a rather involved story. The maps are very

helpful in this context.

Glyn was regarded as the leading financier of his time and the author suggests

that this experience of the management of important monetary operations in

his own bank enabled him to conduct those of the LNWR with so much ability

and success. A whole chapter is devoted to the LNWR's management structure

in which the working of the board and committee structures and the relationship

with senior managers is comprehensively explained. Topics covered include

passenger fares, freight tolls, capital and revenue accounts, audit and the

broad gauge issue. Bearing in mind his banking activities, Glyn seemed to

spend an inordinate amount of his time dealing with LNWR matters, even becoming

involved with a strike of locomotive men at Camden over pay issues.

The LNWR's expansion by way of acquiring connecting railways is well covered

as is the issue of competition versus regulation with Glyn spending a lot

of time lobbying and advising Government on railway policy issues. The LNWR's

Elder Statesman is the heading of a chapter dealing with Glyn's involvement

after he resigned his chairmanship. His successor, George Anson, had been

in office for just a year when he unexpectedly resigned in September 1853.

Glyn seems to have acted as mentor to Arisen's successor, the Marquis of

Chandos who was only 30 and had no previous railway experience. Chandos was

followed by the dominant Richard Moon and Glyn's experience with these two

very different chairmen is very much a feature of this chapter.

His involvement with the Grand Trunk Railway of Canada (GTR) was largely

financial. Glyn's bank, together with Baring & Co., became the London

agents for the Provincial Government of Canada. Both Glyn and Thomas Baring

were somewhat reluctant promoters of the GTR, both men sitting on its

London-based board; Baring was the chairman. The GTR suffered from inflated

construction costs, overestimated revenues and inadequate capital. Throughout

the GTR's financial difficulties, Glyn successfully maintained the moral

high ground, actually meeting many claims from his own pocket.

To all interested in George Carr Glyn, this book is a compulsive read and

will stand the test of time. Insofar as railway history is concerned the

book adds much as to how the new business of running a rapidly expanding

English railway evolved, contrasting markedly with railway pioneering in

Canada. It is essential reading for students of the LNWR with much new

information on its early challenges, management structure and growth. In

summary the book is highly recommended to all railway historians, especially

to those with a keen interest in the LNWR. My only criticism is that a book

of this standing should also have been available between hard covers.

A History of the Southern Railway. Colin Maggs.

Amberley, hardback, 209pp plus bibliography, appendices and maps,. DAT

***

The Southern Railway has been extremely well covered in recent decades,

with quite large volumes only dealing with individual branch lines, so one

always pauses when a new book is published to ask whether new ground is covered,

or new light thrown on the more fascinating aspects. This book inevitably

does not cover significant new ground and is rather more of a useful overview

of the history of the entire system rather than a definitive work.

It has to be admitted that your reviewer was perplexed at the title. One

had expected a heavy focus upon the work of Sir Herbert Walker, Sir Eustace

Missenden, Maunsell and Bulleid, and in particular the way that the SR management

took three largely- steam railways and welded them into the modernised and

enterprising network it became. But instead, the first 164 pages are devoted

to very useful histories of the London & South Western, the London, Brighton

& South Coast, the South Eastern and the London, Chatham & Dover

railways, and the latter two's South Eastern & Chatham Railway offspring.

This leaves a bare 35 pages for the history of the Southern Railway proper,

which is a great shame as the company was in very many ways the most dynamic

and forward-thinking of the' Big Four'. One only has to think of electrification,

timetabling, publicity, station modernisation and the impact of the mercurial

O.V.S. Bulleid to wonder how one could ever hope to do justice to these stories,

amongst others, in such a short space.

Notwithstanding that significant reservation, this is still a good book,

very readable and well-ordered, and the relatively- short chapters make it

an ideal book to dip into. There are chapters on each of the four (eventually,

three) main constituent railways, as well as very brief chapters on the Lynton

& Barnstaple, the Isle of Wight, the London & Greenwich and the London

& Croydon. Separate chapters cover accidents on the main constituents,

and on locomotives, rolling stock and steamer services. At the rear of the

book is a useful though far from comprehensive bibliography.

Perhaps the most useful section is the four appendices, dealing with dates

of line openings, line closures, services converted to electric traction

and the various chief officers of each railway. These have often been overlooked

in previous publications, at least in the form of concise lists, and so the

book makes a really first-rate contribution in this respect. There is also

an eleven-page index, again very useful and often neglected in the past.

Overall, a very readable and useful summary. Perhaps the author could be

persuaded to go on and produce an equivalent volume for just 1923-1948?

Working on the Victorian Railway - Life in the early days of steam.

Anthony Dawson: Amberley Publishing. 96 pp. paperback GSm ***

I must confess this book isn't quite what I expected from the promotional

literature. The title suggests it to be a window into the lives of working

railwaymen in the nineteenth century, which the information on the back cover

qualifies to 'what it was like to drive Rocket and her contemporaries'. In

fact, it's neither and both. A better title might have been 'Rules and

regulations for front-line railwaymen in Manchester during the 19th century',

as this is what the book really addresses. Most of the regulations included

are self-evident safety warnings by the company of the order, 'Don't do this

or you'll kill yourself. However, some make for more interesting reading.

Who would have thought, for example, that 'Guards must prevent Passengers

endangering themselves by imprudent exposure'? Or that on the Great Northern

Railway 'every engineman and fireman must appear in clean clothes every Monday

morning or on Sunday'. Unfortunately, the reader is mostly left to make his

own interpretation of the various edicts.

The author concentrates on Manchester-based railways and the reader is left

to extrapolate as to how management of employees was controlled nationwide.

The city of Manchester figures strongly throughout, since much of the detail

relates to the operation of the Liverpool & Manchester Railway (L&MR).

It has, unfortunately, become fashionable to cite the beginning of modern

railways as the opening day of the L&MR, but it is worth noting that

steam railways had been around for nearly two decades before that particular

railway drew its first breath. The author's narrow view is nevertheless

understandable, given that he is an employee of Manchester's 'Museum of Science

and Industry' (MSI), nevertheless, it will be irksome to, for example, those

currently promoting the bicentenary of the Stockton & Darlington Railway,

which was a steam-hauled public railway that had operated successfully for

nearly five years before the L&MR ever opened up for business. In terms

of the wider perspective the book might have presented, this is a wasted

opportunity. By 1830 there was a wealth of working experience that could

have been drawn on, including many first-hand accounts of daily life recorded

by railwaymen. Dawson's book is therefore a Manchester-centric view of 'life

in the early days of steam' taken from the viewpoint of railway company

management. However, considered purely in this context it works fine.

So what might the reader expect from this book? Well, as the cover notes

suggest, it includes lots of rules and regulations for front-line railwaymen,

alongside the author's personal reminiscences from working on replica locomotives

at the MS!. The railwaymen to which these rules mainly applied were those

operating on the public- faced side of the industry, such as drivers and

fireman (but excluding station staff), and issued by companies during the

first years of public railways in Manchester. Paragraphs from staff regulations

are linked by the author's comments. There are chapters on 'enginemen and

firemen', and 'policeman and guards', although notably absent are the many

other less obvious trades that kept the railways running. This is a pity

because some had an interesting tale to tell. I would love to have known,

for example, what it was like to be an incline brakesman in those dangerous

pioneering years; perched precariously on the last truck, controlling the

movement of a line of accelerating wagons down a steep hill using just a

crude handbrake. Unfortunately, there are no first-hand accounts. No voice

is given to those early railwayman, even though there are many personal stories

to be had dating from the period covered. It would be nice to at least have

a working man's take on the regulations quoted in the book. How much heed

was paid to them remains a matter of speculation, something the author

acknowledges in the penultimate paragraph, The printed material presented

here for the perusal of enginemen and fireman was not the norm: training

was carried out 'on the job' and by word of mouth, rather than through formal

learning.

In my experience, certain employers would rely on rule books to cover their

backs whenever things went wrong, the relevant workplace manual being hauled

out from the back of a dusty cabinet drawer if an inspector called, usually

after a workplace accident. How much easier would this approach have been

in less regulated by-gone days. Certainly, the S&DR, for one, was known

to turn the odd blind eye to bad practice purely in the interest of expediency.

It would be nice, therefore, to know to what extent the regulations referred

to in Dawson's book were ever enforced.

On the plus side the book is well illustrated throughout, even allowing that

nearly half the pictures were taken within the confines of the MSI, with

many featuring the author. A couple of minor niggles. Other than a list of

sources at the end of the book, the regulations quoted are unreferenced,

nor is there an index, which would have helped navigate around the book easier.

Also, the retail price of £14.99 seems excessive for a book consisting

of less than a hundred pages. However, if you are interested in finding out

what rules were imposed by early railway companies on front-line staff, or

would like to know how to fire up and operate an early engine then this is

the book for you. If, however, you still wonder what it was like to actually

work on Victorian railways, from the perspective of the railwayman involved,

then you may have to look elsewhere.

What it was like at Kenilworth. David P. Williams. rear cover

Precursor 4-4-0 No. 25319 Bucephalus [coloured photograph in

which there is lttle colour other than on LMS maroon coaches, fields and

trees]

Class 37 No.37 109, in EWS red livery, at Hoo Junction with

the 08.55 freight from Temple Mills yard on 26 November 1996. Rodney

Lissenden. front cover

More of similar Class 37 in colour

"A little rebellion now and than is a good thing". Michael Blakemore. 131

Seen on shed. Geoff Rixon. 132-3.

Colour photo-feature: Nos 65267 and 65282 (Reid NBR 0-6-0s in late

BR steam livery) on Bathgate shed in September; J94 0-6-0ST No. 68070 at

Colwick on 25 August 1962; 61XX No. 6111 at Oxford coaling stage in May 1962;

Vale of Rheidol sheds at Aberystwyth with No. 9 Prince of Wales barelly visible

and No. 8 Llywelyn partially visible on 10 June 1963; Q7 0-8-0 No. 63466

at Tyne Dock in September 1962 .

Michael H.C. Baker. To the Kent Coast and across the

Channel. 134-8

Written by Railways to the Coast author — a mixture of

personal experiences of travel to the Continent by train and ship prior to

the opening of the Channel Tunnel plus a brief examination of the history

of such journeys matched by interesting illustrations. In 1824 Thomas

Telford was engaged to connstruct a railway from London to Dover

along the course of Watling Street via Rochester and Canterbury, but this

failed to materialise. Parliament sanctioned a line which branched off the

railway to Brighton and then ran virtually straight to Ashford and on tp

Folkestone, completed in June 1843 and Dover reached in February 1844 via

a tunnel under Shakespeare Cliff. Charles Dickens tended to depict travel

to The Continent in pre-railway days — by stagecoach in Tale of Two

Cities, but suffered severely by being involved in the Staplehurst accident.